Singing out against war

4/13/2003

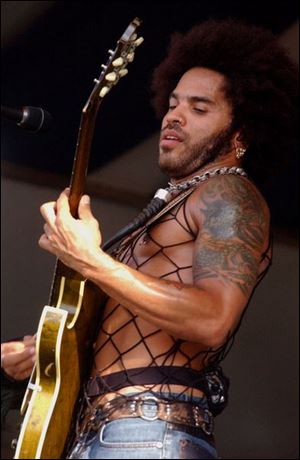

Lenny Kravitz offers (“We Want Peace); as a protest song.

Bruce Hannam can pinpoint the moment everything went bad. It was when Joan Baez announced that she would now be singing the national anthem of Finland, in Arabic. The audience at the Ritz Theatre in Tiffin shifted uneasily.

This was late last month, and two days earlier the first U.S. bombs had blasted Baghdad. Baez explained that when she was a child, she lived in Baghdad for a year, and recalled how wonderful the country was, how beautiful the people were. More shuffling from the audience of 800.

Someone yelled up to the singer: Sing the national anthem of this country. Baez scanned the audience and located the person who yelled it. From the stage she locked eyes with him and said no. Then she proceeded to sing the Finland national anthem in Arabic as promised.

This was a bizarre tale from the front lines of a curious new skirmish between anti-war musicians, young and old, singing protest music and an audience either not entirely receptive or just not hearing the message to begin with. Baez, that angelic-voiced '60s icon who, with Bob Dylan, popularized the folk movement against Vietnam, had come full circle.

After every subsequent song, Baez would make another comment about the war, remembers Hannam, the Ritz marketing manager. “And with every song people were getting more restless. You could see it. Husbands leaning over to wives and saying `Let's go.'” People began to leave. Then Baez pulled out a transcript of Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger discussing the possibly of nuking Vietnam; it's an ugly back-and-forth, full of derogatory slang and profanity, and Baez was consciously provoking, drawing attention to that ugliness. The audience muttered about poor taste, poor timing. More people got up and left.

“At one point it felt like a mass exodus,” Hannam said. In the end, about 100 audience members had bolted.

You know it's a strange time for protest music when people walk out of a Joan Baez concert because she's being too political. From John Mellencamp to the Dixie Chicks, from Pearl Jam to the most politicized indie acts, from bar bands to Madonna, the music industry has been thinking: There's something happening here, but what it is ain't exactly clear. Could it be too early for protest music? Is the audience too cynical? The music no good?

Or could it be that wartime has become the least conducive time for music to speak against war?

The irony is that because of the Internet it's never been easier to record and widely distribute a protest song. Among the significant artists who have posted confrontational anti-war tunes in the last few months are Nanci Griffith (“Big Blue Ball of War”); Lenny Kravitz (“We Want Peace); Public Enemy's Chuck D (“A Twisted Sense of God”); R.E.M. (“The Final Straw”); Beastie Boys (“In a World Gone Mad”); Spearhead (Bomb the World); and Billy Bragg (“The Price of Oil”).

When the bombs started falling, Toledo singer-songwriter Laurie Swyers quickly penned “Bush's Stinkin' War.” (“It's not a musical masterpiece,” she said, “just a statement.”) She made just 50 copies, handing them out at area protests, as well as at Lucas County Children Services, where she works. Reaction around the office was mixed.

“A lot of people think that entertainers should shut up and entertain,” she said. “But art has always proceeded social change. So I don't get their reaction. Writers of music who tackle problems have always come up against the popular music machine - but I don't think it's ever been this bad.”

After the Baez show, the Ritz got a lot of phone calls. One suggested suing the singer. Another demanded she write an apology to area veterans. Another wanted to know why the theater didn't control what she said. “I think in the end the situation made everyone more aware,” said Hannam. “It strengthened your resolve, on both sides of the issue. What killed me was that it seemed to escape everybody she has a right to think for herself.”

Likewise, in the days leading to the war, the Dixie Chicks watched their stock plummet when fans and radio stations trashed their CDs after they publicly criticized George Bush. At a Pearl Jam concert in Denver, singer Eddie Vedder impaled a Bush mask on a microphone stand. Again, fans bolted. Radio conglomerates like Clear Channel, which owns 1,200 stations including five in Toledo, have yanked any song with anti-war sentiment - as far flung as John Lennon's “Imagine” to the entire catalog of Rage Against the Machine - from their playlists, while organizing pro-war rallies and placing pro-war songs like Darryl Worley's “Have You Forgotten” into heavy rotation. It's currently Billboard's No. 1 country song.

“My feelings about the conflict are so complex that I don't really know what to say,” said Stephan Jenkins, leader of the rock group Third Eye Blind, “except that, on the home front, I think we need dissent in this country. I think that whatever people's views are, dissent is not un-American. And it's not unpatriotic. It does not hurt war efforts for people to disagree.

“If the Dixie Chicks want to say they're embarrassed about George Bush, then let them. It has nothing to do with their music. They have a right to say what they want.”

“Today it seems you have to own a string of radio stations like Clear Channel to really reach people,” said John Sinclair, the former White Panther leader from Ann Arbor who managed the seminal proto-punk band MC5 during the late 1960s. “If you did make a protest song, would they play it? Doubtful. [In the 1960s] we acted with the idea you could make a difference. It became obvious we were having an impact when we were getting arrested.”

Take MTV: The only protest song receiving any significant play on the cable channel is System of the Down's “Boom!” which boasts a video by Bowling for Columbine director Michael Moore, who shot the footage during a Feb. 15 anti-war rally. But the network still refused to air anti-war ads from Def Jam founder Russell Simmons, while its sister channel, VH-1, edited out Neil Young's anti-war remarks during a telecast of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony.

Closer to home: in the days leading up to a concert last Friday by the notably outspoken Ani DiFranco, management at the Stranahan Theater fretted over the idea that she might invite anti-war protestors to speak between songs, as she did at a tour stop in New Jersey.

Stranahan manager Ward Whiting said he asked that she use a table in the lobby for any anti-war messages, but “her music of course has political undertones anyway. So as a venue operator I find myself trying to find a comfortable match between her First Amendment rights and the patron's right to enjoy themselves. I'd prefer the speeches be kept to a minimum.”

Strangely, so would some musical icons of the Vietnam protest movement. Paul Kantner, one of the co-founders of Jefferson Airplane, said he wishes musicians were updating their language and slogans, instead of using the same old songs from the 1960s. He won't perform anti-war songs during his shows with the reconfigured Jefferson Starship, and he won't make speeches about the war, either. But that is not to say he isn't torn: Kantner said he doesn't support the war, but he hopes Saddam Hussein gets what he deserves.

Still, music's history with war tells us it's time for a high-voltage wake up call - “a public service announcement, with guitars,” as the Clash once said. For decades, popular music has been one of the most telling gauges of the emotional state of the union. But in the past, the time span between a current event happening, a song inspired by it being written, and that song then being played on your local radio station might have been months or years.

Now, it's minutes and hours, and the backlash can be just as fast. Take the case of John Mellencamp's “To Washington,” mailed to radio stations in March, and quickly picked up by Mike McIntyre, the afternoon drive time host and assistant program director for Toledo's WXKR-FM.

He played it - once.

“I didn't play it in support of any one side. I didn't take a stance. I played it because it's Mellencamp. But there was a huge negative reaction. We were told [by station management] never to play it again, ever.” Listener reaction was evenly split, with half in favor, and the song still gets requests. As does Bruce Springsteen's cover of “War,” that quintessential Vietnam-era soul hit from the late Edwin Starr - but again, McIntyre is not allowed to play that one either.

“I am so uninterested in hearing what popular music has to say anyway,” said Dustin Amery Hostetler, 25, a singer in Bowling Green's “new, new wave” band Stylex. “My parents had a different interaction with popular music, I think, because I generally don't trust it. If Britney Spears did a protest song it would obviously be a career move. I only trust the bands that aren't getting anything financially out of their protest.”

Hostetler has a kindred soul in Thurston Moore, leader of the legendary New York City rock group Sonic Youth. There's a general fatigue at the moment about protest, he said, “a sense of devaluation. But protest music, first and foremost, is really about making people aware.”

So last month Moore launched protest-records.com to house the growing anti-war songbook; it's a kind of one-stop shop, including songs from Cat Power, DJ Spooky, and Jonatha Brooke. He's up to 60 tunes, and it's all free.”

And yet David Siglin is still hearing mostly the old protest standards being sung in his club, The Ark, an Ann Arbor folk music mainstay that he has run since 1968. If the war dragged on for six more months, a few new protest songs would catch on, he said. It's just too soon.

“People forget that Vietnam songs like `I Feel Like I'm Fixin' to Die Rag' and `All Along the Watchtower' didn't get a lot of airplay during Vietnam, if any,” he said.

Or perhaps the times are too uncertain for easy slogans, too complicated for self-righteous chants. Lee Hirsch, director of Amandla! A Revolution in Four Part Harmony, a new documentary about how protest music helped fuel the anti-Apartheid movement in South Africa, has joined anti-war protests in New York.

“Nobody is singing at all. They're just chanting. There's no longer a connection to song. There's way too much noise: a group here chanting, a group there chanting something else louder to be heard over the first group. I hope they realize music has a pulse, a rhythm, an energy that keeps you marching.”

Toledo's Laurie Swyers would just like to hear something good, anything.

“I'm very frustrated by the inability of musicians to say something meaningful. Whether people agree or disagree. At least an alternate view. I don't understand why sex and violence is acceptable, but songs about racism, poverty, or the corporate machine are not. I can't fathom how our values have changed. You know, I have a poster at home that keeps me focused.”

It's a picture of Woody Guthrie, the great-grandfather of the modern protest song, and on the body of his guitar is a simple message: “This machine kills fascists.”

Blade staff writers Tahree Lane and David Yonke contributed to this story.