Everything s bigger than life for legendary rock critic Greil Marcus

8/26/2007

COLUMBUS Greil Marcus looked like someone who was someone, even if no one here had a clue who that someone was. He moved through University Hall with efficiency, head bowed; he would look up as needed, when a turn arrived in his path or someone spoke. Otherwise, he had the deliberateness of a Secret Service agent; so impressively streamlined were his movements that the students he passed, curled into window boxes, couldn t help but notice.

Heads rose.

His remained buried behind the upswept collar of his black wool overcoat, which matched his black pants, black shirt, oval tortoiseshell frames, and dour expression, topped with an austere head of white hair. Here was a man used to being taken seriously and who, in turn, took everything seriously. Too seriously, some say. After 10 books and five decades as the most grim-faced and rigorous of celebrated rock critics, after practically inventing the job, his solemnly declared grandiosity (Dylan s Like a Rolling Stone was a rewrite of the world itself ; punk rock was a seminal turning point in Western civilization) sounded as pretentious as it was persuasive.

Elder statesman, they call it.

He arrived at his destination. The plate on the door said Barry Shank, a professor of comparative studies here at Ohio State University. Marcus knocked once and Shank opened the door as if he d been waiting all morning for that knock. His face looked as thrilled as Marcus looked polite. Shank stepped aside to reveal a worn copy of Mystery Train on his desk; he asked the 62-year old author to sign the book, which had been written in his late 20s. Marcus did not hesitate. Nor did he seem especially surprised. It s the book that put him on the map, often called the best ever written about rock and roll.

And the most pompous.

They walked down the hall, and Shank opened a door, behind which students were getting settled, shoving bicycle helmets into backpacks, flipping through notebooks. Shank couldn t wait. He threw an arm around Marcus and, as if introducing a long-lost brother, he said: I ve been having a conversation with this man, in my head, for 30 years.

Not a bad way to put it.

But argument is more apt.

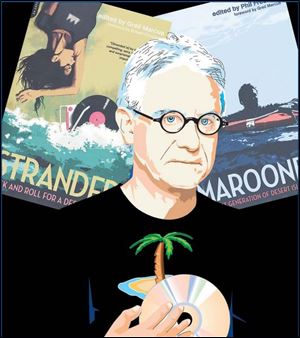

Actually, if you feel the need to quibble with your inner Greil, the time is ripe: His most loose-limbed work, 1978 s Stranded ($16.95, Da Capo), was recently reissued: It famously asks 20 writers to wax eloquent on the one album they would take to a desert island if they could only choose one. No nostalgia act, Marcus contributes the forward to Marooned ($16.95, Da Capo), a companion volume that poses the same question to a new, iPod generation of critics. Then there s the paperback debut of his latest book, The Shape of Things to Come: Prophecy and the American Voice ($15, Picador) a vintage Marcus plunge into Americana and its discontents, by way of David Lynch, the TV show 24, the origins of Puritanism, Cleveland s Pere Ubu, and a couple of other touchstones that don t seem to fit but, indeed, do.

So, blame him.

This fall, when Rolling Stone celebrates its 40th anniversary, Marcus, who got his start as the magazine s first record review editor, will have been doing this since 1967 himself. Along with Lester Bangs, his friend and fellow critic (who died in 1982), he remains one of the few original voices in cultural criticism the Pauline Kael of music writing. But again, if you hate rock critics, and the purple nonsensical hyperbole of rock criticism and the inflated sense of importance, blame him. He was too skilled at a job that appeared too easy and imitators became legion.

You could argue Stranded created the parlor game aspect of rock criticism name the five best songs to play at your funeral, pick the five best Velvet Underground songs about heroin that often acts as substance today (even if the premise is identical to the decades-old BBC TV series, Desert Island Discs). And with Mystery Train which saw the embodiment of America and all its promise and failures in two blues singers and three rockers (Elvis Presley and Herman Melville are a stone s throw apart) well, there s the hype.

And the possibilities.

What Marcus does is closer to what universities call American Studies, though Umbrella Studies often seems more appropriate. In Lipstick Traces (1989), the onset of Medieval Europe had to lead to the birth of the Sex Pistols; in Invisible Republic (1997), Bob Dylan s Basement Tapes is the natural outgrowth of backwoods myths and Manifest Destiny; and in Shape of Things, America is a place and a story, made up of exuberance and suspicion, crime and liberation, lynch mobs and escapes; its greatest testaments are made of portents and warnings, Biblical allusions that lose all their certainties in American air. Whew.

In a Marcus sentence, every idea is a universe, and every song is a seismic disruption of the tectonic plates of American culture. Do not try this at home. Can you make too much a song? Sure. Like a Rolling Stone was not merely a single but a world to win. Every singer raises the stakes and every song is a vortex, sucking in a nation s history.

Frankly, he s exhausting.

The sort of critic who tries to explain an entire culture by way of track four on an album, as Rolling Stone s Anthony DeCurtis once put it. But he s compelling, because he hears different.

Back in that classroom, on a chilly spring day last semester at OSU, once Marcus settled in, the conversation took the loping, digressionary path of his books, and the students sat rapt. It began with a chat about the American crank, which Marcus calls central to America someone without power but with conviction, who will not pipe down. This segued into a discussion of South African playwrights, then a student said her project was on karaoke, how there s something beautiful in, like, the worst karaoke performance you know?

Marcus smiled and nodded.

He said, But is it failure or self-discovery? Bill Murray in Lost in Translation singing More Than This. Until I saw that I realized I had never heard that song before, not really. His focus was on the words, and how desperately he wanted to convey them, which read on that forlorn face. You meant beautiful like that?

The student paused, then nodded. Professor Shank broke in with another example. He said, Janis Joplin and her performances could be taken as a withering reproach or as a conversation.

Marcus listened, then said:

Once he was in a band with Stephen King and Dave Barry, and Don Henley wrote a review of their show for LA Weekly and it had this what-gives-you-the-right-to-sing tone, which was not so far from telling black people they can t vote, because it can feel just as oppressive and as for Janis, he was there, at the Monterey Pop Festival when she did Ball and Chain, and it was this performance that called to mind the Greeks and their tragedy and how an act playing a hero implied that truly, right there, on stage, his heart has burst open.

With Janis, I heard a resistance building up, a singer drawing on everything she has, even though it was a performance.

Rehearsed, a student said.

Yes, Marcus replied. So?

Contact Christopher Borrelli at: cborrelli@theblade.comor 419-724-6117.