Dick Clark was chaperone to generations of music lovers

4/20/2012

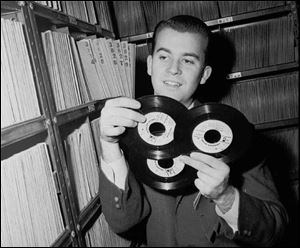

In this Feb. 3, 1959 file photo, Dick Clark selects a record in his station library in Philadelphia.

It seems inconceivable that Dick Clark -- eternally youthful, frightfully busy Dick Clark -- has died. It's as if, through some cosmic foul-up, Death did not get the memo excusing him from such a mortal distraction.

And yet, he has, Wednesday in Los Angeles, of a heart attack at the age of 82. New years will still come and go, but we have come to the end of Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve -- a holiday he managed to brand, in pop consciousness, as his own -- or, at any rate, one which he is available to host. America, you will have to make other plans.

More than the bare recitation of his on-screen and behind-the-screen credits would suggest -- he was a television personality, the host of a dance party, of game shows (most notably of the Pyramid franchise, over some 15 years) and of a series called TV's Bloopers & Practical Jokes -- he was a force not only in the history of the medium, but of the culture at large.

In the years before MTV, Clark's was the name most associated with rock and roll music on television, although there was nothing much rock and roll about the man himself. Born in 1929, he was a teenager not in the era of Elvis but in the twilight of the big bands, and as the host of American Bandstand for more than 30 years -- a show he did not create but came to own, in the vernacular and the literal sense of the word -- he played the role of chaperone to generations of teenagers at a kind of national hop.

Indeed, what made him compelling was the way the dual strands of his nature and his businesses combined in the person you saw onscreen, entertainer and executive, agent of fun and serious businessman. He was an adult involved in childish things.

Often called "America's Oldest Teenager," he retained his thick-maned, white-smiled, boyish looks into an age that visibly crumpled his peers into senior citizenry. And yet, even in the days when pop music was his daily bread -- even in the earliest days, when he looked not much different from the kids that crowded around him on the Bandstand set -- he never came across as a kid.

Rather, Clark was a voice of friendly authority. (An authority, one also felt, that could turn stern in a minute -- that was the mogul you could glimpse through the mouthpiece.)

That voice, bruised but not broken by a stroke in 2004, was a trained instrument whose sound caught his doubleness: perfectly warm, perfectly cool.

There was always a poise about him, a pressed quality that a cyclone could not ruffle. You felt that he wouldn't break a sweat on a summer's day in the Sahara. But he rarely seemed stiff.

As a sideline, he occasionally appeared in dramatic roles in episodic television series, including Lassie, Adam-12, and Perry Mason, in which he played a killer. He played one again in a film he co-wrote, Killers Three, from 1968. I don't want to read too much into that, but I find it not uninteresting.

You can't rate a life as you could a record, but one would say, after all, that this one had a good beat.