DEADLY ALLIANCE: WEAPONS OVER WORKERS

Decades of risk: U.S. knowingly allowed workers to be overexposed to toxic dust

12/27/2012

Gary Renwand uses an inhaler at St. Charles Mercy Hospital. He contracted beryllium disease at Brush's Elmore plant, where he helped produce beryllium for U.S. weapons. Records show he was repeatedly exposed to levels of beryllium dust five times the safety limit. He says: "We're killing ourselves trying to kill someone else."

BLADE/CHRIS WALKER

Beryllium was an essential metal during the Cold War. Among the uses: heat shields for the Mercury manned flight program.

Over the last five decades, the U.S. government has risked the lives of thousands of workers by knowingly allowing them to be exposed to unsafe levels of beryllium, a material critical to the production of nuclear weapons.

As a result, dozens of workers have contracted beryllium disease, an incurable, often-fatal lung illness.

In the Toledo area alone, at least 39 workers have contracted the disease after being exposed to levels of beryllium over the federal safety limit. Six of these workers have died.

A 22-month investigation by The Blade shows that the U.S. government clearly knew, decade after decade, that workers in the private beryllium industry were being overexposed to the hard, lightweight metal, which produces a toxic dust when manufactured or machined.

But federal officials continued to subsidize and encourage the industry to produce beryllium despite numerous government, scientific, and company reports showing that the material could not be made without putting workers in extreme danger.

Some workers were exposed to levels of beryllium dust 100 times above the safety limit, the government's own contemporaneous records show.

DEADLY ALLIANCE: How government and industry chose weapons over workers

When safety regulators tried to protect workers, they ran up against an overwhelming alliance: the beryllium industry and the defense establishment.

Protection of the industry has reached all the way to the White House cabinet, where in the 1970s President Carter's Defense and Energy secretaries helped kill a safety plan.

1,200

Estimated number of documented cases of beryllium disease in America since the 1940s

1 in 11

Workers at the Elmore, O., beryllium plant who, according to a recent study, either have beryllium desease or an abnormal blood test

39

Number of local Brush workers who have contracted beryllium disease after documented overexposures

They feared the plan would cut off beryllium supplies for weapons, and that would "significantly and adversely affect our national defense," U.S. Energy Secretary James Schlesinger wrote to two cabinet members at the time.

The Blade investigation, based on tens of thousands of court, industry, and recently declassified government documents, reveals a decades-long pattern of the government putting beryllium production and costs ahead of worker safety.

"The [government] cannot stand for a cessation of production," one federal official, Martin Powers, told colleagues in 1960 in response to health concerns.

Dr. Peter Infante, director of standards review for the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, says the government has done a poor job protecting beryllium workers.

"These are all deaths and disease that could have been prevented," Dr. Infante says. "That's the sad thing about it."

Victims question why the government risked their lives for weapons.

"We're killing ourselves trying to kill someone else," says Gary Renwand, a 61-year-old who contracted the disease at the country's largest beryllium plant, outside Elmore, O., 20 miles southeast of Toledo.

Among the local workers who have died:

Gary Anderson, a former Elmore high school football star.

Marilyn Miller, the wife of a dairy farmer in Bradner.

Ethel Jones, a Fremont, O., resident whose son, Eric Johnson, also contracted the disease.

Others have had their lungs so ravaged that they can no longer breathe on their own.

"If they had told me I'd end up hooked up to an oxygen tank my whole life I would have run away from the damn place," says Butch Lemke, who was overexposed at the Elmore plant and has been on oxygen for 15 years.

No one knows how many people have ever contracted the disease. Researchers estimate 1,200 documented cases nationwide and hundreds of deaths. But they say the disease often is misdiagnosed or goes undetected.

And it is difficult to determine how many victims have had exposures above the safety limit.

This much is clear: Beryllium disease has emerged as the No. 1 illness directly caused by America's Cold War buildup.

"I know of no other disease that we can document that is solely attributable to the work that we have conducted in the production of nuclear weapons," says Dr. Paul Seligman, director of the Energy Department's Office of Health Studies.

Among The Blade's findings:

- Decade after decade, the government has knowingly allowed workers at privately operated beryllium plants in Ohio and Pennsylvania to be exposed to amounts of beryllium dust far above the U.S. safety limit. The plant outside Elmore, owned by Cleveland-based Brush Wellman Inc., has never consistently complied with the safety limit in all parts of the facility.

- Production and costs have been put ahead of safety even when workers were in danger. In one case, federal officials said it was policy that saving money would come before safety when choosing some beryllium suppliers.

- Safety enforcement by OSHA has been virtually nonexistent. Even though dozens of workers have contracted beryllium disease at the Elmore plant, several of whom have died, OSHA has conducted only one full inspection of the facility in the past 20 years.

- Even though beryllium is a highly toxic material, the government has little idea which companies are using it, how many people are exposed, and whether they are being protected. This means thousands of Americans may be exposed to dangerous amounts of beryllium and not even know it.

- Despite mounting illnesses and deaths, the government has not tightened exposure limits in 50 years. It has tried only once, and the Carter administration stepped in and helped kill the plan.

Long a strategic metal, beryllium is lighter than aluminum and six times stiffer than steel. It makes nuclear weapons more powerful, missiles fly farther, and jet fighters more maneuverable.

And it has been critical to the space program, having been used in the early Mercury missions, the space shuttle, and the Mars Pathfinder.

But when the metal is ground, sanded, or cut, and the resulting dust inhaled, workers often develop a disease that slowly eats away at their lungs. About a third with the illness eventually die of it.

Scientists still consider the illness mysterious - even bizarre. Tiny, invisible amounts of beryllium dust can be deadly; the federal exposure limit - 2 micrograms per cubic meter of air - is equivalent to the amount of dust the size of a pencil tip spread throughout a 6-foot-high box the size of a football field.

And while some people are unaffected by the dust, others get sick at seemingly insignificant exposures. So researchers think some people are genetically susceptible to the illness. Those individuals often develop the disease years after their last exposure to beryllium - up to 40 years later.

Federal officials have not been oblivious to the illness. Millions of dollars have been spent to improve safeguards and identify victims.

And it is unknown whether every single beryllium worker has been overexposed; the available exposure data are too sketchy.

Around the world

At least 46 cases of beryllium disease have been reported in Japan and at least 40 in Great Britain. Hundreds of cases have been reported at a beryllium plant in Kazakhstan, a former Soviet republic.

1. Tucson, Ariz.

Eighteen current and former workers at a Brush Wellman plant have beryllium disease, and 13 more have abnormal blood tests.

2. Golden, Colo.

Eighty-six current and former workers have contracted the disease at the former Rocky Flats nuclear weapons plant; 171 more have abnormal blood tests. Now called the Rocky Flats Environmental Technology Site, the plant is being torn down. It is owned by the U.S. Energy Department and managed by Kaiser-Hill Co.

3. Oak Ridge, Tenn.

Twenty-eight current and former workers at the Oak Ridge Y-12 nuclear weapons plant have contracted beryllium disease; 60 more have abnormal blood tests. The plant is owned by the U.S. Energy Department and managed by Lockheed Martin Energy Systems.

4. Luckey

Six workers contracted beryllium disease at a plant owned by the U.S. government and managed by Brush Beryllium, predecessor to Brush Wellman. It was open from 1949 to 1958.

5. Elmore, O.

Fifty current and former workers at Brush Wellman's beryllium processing plant have the disease. Of those, at least 39 have documented overexposures.

6. Lorain, O.

At least 21 workers contracted beryllium disease at a plant operated by Brush Beryllium, predecessor to Brush Wellman. It closed in 1948. More than 20 residents who lived near the plant but who never worked there also contracted the disease; at least six died.

7. Cleveland

Twenty-three workers contracted beryllium disease at two Brush Wellman facilities that are now closed. At Brush's corporate headquarters, which includes a research area and small machine shop, several employees have been diagnosed with the disease.

8. Hazleton, Pa.

About a dozen former workers of a beryllium plant have been diagnosed with the disease; 65 others have an early indicator of the illness. The plant opened in 1957 and was operated by the Beryllium Corporation. It closed in 1982.

9. Reading, Pa.

At least 31 workers at a beryllium plant have contracted the disease, with some deaths. About 60 residents who lived near the plant but who never worked there developed the disease. Ownership of the plant has changed several times. It is now owned by NGK Metals Corp.

10. Salem, Mass.

Numerous cases were reported at a Sylvania Electric Products fluorescent lamp plant as a result of beryllium exposures in the 1940s. Researchers in 1946 reported 17 cases, including six deaths. More than 300 cases were eventually discovered in the fluorescent and neon light industry.

Nor is it known precisely what constitutes a safe exposure. Exposures over the federal limit do not seem to guarantee illness, and exposures under the limit may not guarantee safety. In fact, more and more scientists think that people can get sick at levels under the limit.

What remains clear is that over the years, beryllium plants with close governmental ties have consistently exceeded the federally mandated safety limit with the government's full knowledge, and workers in those facilities have gone on to develop the disease.

Martin Powers, a former U.S. Atomic Energy Commission official in charge of obtaining beryllium for the government in the 1950s, says federal officials knew about the high exposures and tried to control them.

But he says the government did not want to shut the plants because that would mean stopping weapons production.

"What is the greater risk? To possibly expose people to health injury in the plant or shut down the national defense?"

Mr. Powers, who left the government to become a beryllium industry executive, says workers, at times, were put at increased risk for national security reasons.

"You know you are putting them at increased risk. You hope the risk doesn't materialize, doesn't become a reality."

The Energy Department, which is responsible for maintaining the nuclear weapons arsenal, says there are no substitutes for beryllium. So as long as America wants bombs, workers will face dangers.

"Building weapons is an extraordinarily risky process," the Energy Department's Dr. Seligman says.

Some victims say they knew there was a risk, but they didn't know they were being overexposed.

Brush Wellman, America's largest beryllium producer, says it has always posted air test results on plant bulletin boards and has discussed high exposures with employees.

But it acknowledges that by the time high dust counts are discovered, workers have already been overexposed.

Magical metal turned deadly

Discovered in France in 1798, beryllium wasn't produced commercially in America until the 1930s. When it was, it was extracted from beryl and bertrandite ores and processed through a series of chemical steps.

Among the first uses of beryllium: fluorescent lights. Workers coated the insides with beryllium-containing phosphors to help make the glass tubes glow.

At the time, beryllium dust was considered harmless. No one wore respirators, and no one appeared to be getting sick.

Then came World War II.

Suddenly, the U.S. government needed tons of beryllium for the top secret Manhattan Project, the $2 billion effort to build the world's first atomic bomb.

Beryllium plants signed government contracts and began shipping orders to Manhattan Project sites. To maintain the secrecy of the project, shipments were in unmarked packages, identified only by code names, such as Product 38.

"The word 'beryllium' should never be used," one government document warned.

In 1943, federal officials ran into a problem that threatened supplies: Beryllium workers, many in the Cleveland area, began developing a mysterious illness.

They were coughing, losing weight, and becoming breathless. Many recovered, but some grew sicker and died.

A Cleveland Clinic doctor concluded in 1943 that beryllium dust was toxic. But the U.S. Public Health Service, in a report that same year, thought some other agent was to blame.

As the controversy brewed, the government stepped up its beryllium orders. When the factories couldn't keep up, the government spent millions to expand them.

By the mid-1940s, dozens of people had become sick, both at Manhattan Project sites and in the fluorescent light industry.

And the mysterious disease was exhibiting a new twist. Researchers studying the fluorescent light industry concluded in 1946 that workers were getting sick months - even years - after their last exposure to beryllium. No one was recovering from this form of the illness, which would become known as chronic beryllium disease.

By now, most scientists and industry leaders agreed that beryllium dust was toxic.

The government recommended safety improvements and supplied respirators for some workers. But it was also deeply concerned about its image.

A 1947 secret report by the newly formed Atomic Energy Commission, or AEC, warned that the disease "might be headlined, particularly in non-friendly papers, for weeks and months - each new case bringing an opportunity for a rehash of the story. This might seriously embarrass the AEC and reduce public confidence in the organization."

Despite mounting sickness, the AEC remained "acutely interested in maintaining and expanding production of beryllium," according to the report, which was recently declassified.

The agency's mission - building nuclear weapons - depended on it.

"The AEC appears to be stuck with beryllium," the report said, "and hence stuck with the public relations problem."

Gary Renwand uses an inhaler at St. Charles Mercy Hospital. He contracted beryllium disease at Brush's Elmore plant, where he helped produce beryllium for U.S. weapons. Records show he was repeatedly exposed to levels of beryllium dust five times the safety limit. He says: "We're killing ourselves trying to kill someone else."

Disease strikes Lorain residents

Just weeks after the government outlined its public relations fears in 1947, a tragedy began to unfold: People living near a beryllium plant in Lorain, O., started coming down with the disease.

One 28-year-old woman dropped to 85 pounds. Another became so weak she had to remain in bed.

Government officials were stunned. Never before had people been known to contract metal poisoning by living near a factory.

Fear in Lorain spread quickly. Citizens stormed a city council meeting, and Councilman Leo Svete had to pound the gavel for 15 minutes to restore order.

The AEC took air samples around the plant, and the Ohio Health Department announced it would conduct a rare and massive project: It would X-ray as many Lorain residents as possible.

X-ray stations were set up at schools, JC Penney, and Abraham Motor Sales. In all, 10,500 people were X-rayed - a fifth of the entire city.

And when the inquiry was over, 11 citizens who had never set foot in the plant were found to have the disease.

The wife of one worker got it by handling her husband's dusty work clothes. But the other victims, the AEC found, got it strictly from beryllium air pollution.

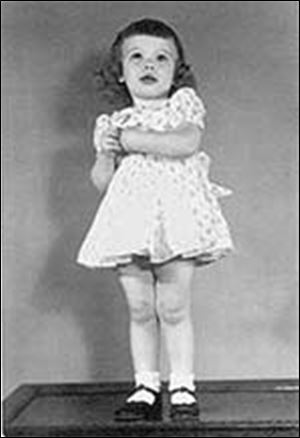

Among them: 7-year-old Gloria Gorka, a chubby girl with curly hair.

"We noticed she kept panting and had a hard time breathing when she exerted herself in the least little way," recalls her father, Joseph, an 81-year-old now living in Florida. "We just thought she was having a hard time getting over the measles."

When her schoolteacher called and said Gloria was having difficulty walking up one flight of stairs at school, her parents took her to a doctor. But there was nothing anyone could do.

"It was so sad," recalls her 79-year-old aunt, Angela Barraco. "By the time she died she was nothing but skin and bones."

AEC officials concluded that the victims had been exposed to surprisingly minute levels of beryllium. They recommended that citizens should no longer be exposed to more than .01 micrograms per cubic meter of air - an amount invisible to the naked eye.

The limit was the first air pollution standard in American history.

As for the limit inside beryllium plants, officials weren't sure what to do. They discussed the matter for weeks, and then an AEC health official and a medical consultant to the fluorescent light industry settled on 2 micrograms while riding in a taxi.

This limit, based largely on guesswork, was dubbed "the taxicab standard."

Officials knew workers might become ill at lower levels, a 1958 AEC report states, but "because of the relatively small numbers of people involved," it was seen as "an acceptable risk."

Costs made a priority over worker safety

Publicly, the government was cracking down.

While the AEC was setting limits on pollution, the U.S. Public Health Service was convincing fluorescent light companies to stop using beryllium.

Government officials issued warnings about the lights already in use: Children shouldn't use them as lances, and burned-out tubes should be broken under water.

But unbeknownst to the public, the government was embracing beryllium, ordering more for weapons.

In fact, in 1949 the AEC adopted a policy that weapons production and economics would come before worker safety when the United States was choosing some beryllium suppliers.

One top official who was upset about this, records show, was Wilbur Kelley, manager of the AEC's New York office.

In the summer of 1949, he and his staff were concerned that the government was planning to buy beryllium hydroxide - the vital feed material for all beryllium products - from a plant outside Reading, Pa., operated by the Beryllium Corporation.

Mr. Kelley had reason to be concerned: Dust in the plant was hazardously high, and several workers had died.

In a series of letters, Mr. Kelley pleaded with his AEC colleagues not to buy beryllium from the firm.

"The AEC cannot avoid knowing that every time it enters into a contract for the production of beryllium in what it knows to be a medically unsafe plant the lives of an unknown number of people may be placed in jeopardy," he wrote.

The government, he wrote, "cannot shirk its moral responsibility in this matter."

But at a meeting of top AEC officials in Washington, Mr. Kelley was informed that, except in certain contracts, the government would no longer bear "the responsibility for health conditions associated with the procurement and production of beryllium materials," minutes of the meeting state.

It was decided that "further consideration of medical reasons would be dropped and that all consideration of the proposed arrangement with the Beryllium Corporation would be based strictly on economics."

It is unclear whether the AEC went ahead and bought beryllium from the Beryllium Corporation. But the government continued its association with the firm.

The AEC owned a small building on plant grounds that cast beryllium metal. The Beryllium Corporation ran the casting operation under a government contract.

For the next 20 months, from the summer of 1949 to the spring of 1951, workers in that building were exposed to dust up to 100 times the safety limit, records show.

Conditions in Beryllium Corporation's main plant were worse: Some workers were exposed to dust 500 times the limit.

And many people went on to get beryllium disease.

In fact, in the 10 years following Mr. Kelley's repeated warnings about the Beryllium Corporation, at least 37 people either working at the plant site or living nearby developed the illness, studies show.

Among them: a woman who paid weekly visits to a relative's grave in the cemetery across the street from the plant.

Plants kept open despite dangers

The 1950s brought the Korean War and the arms race, the Cold War and the space race. America's desire for beryllium had never been greater.

The government didn't want a repeat of the Lorain neighborhood tragedy, and so it paid Brush Beryllium, the predecessor to Brush Wellman, to build and operate a plant far from residents.

The site: tiny Luckey, a farming community 15 miles south of Toledo. Here, only one or two farmhouses would be near.

And for the first time, the government had a safety standard - the one adopted in 1949 - to limit the amount of dust workers could be exposed to.

But year after year, records show, dust counts in the Luckey plant were high. Workers were even overexposed in the lunchroom.

Instead of closing the plant, the government eased enforcement of the rules, allowing workers to be exposed to levels five times higher than previously permitted.

But even with the relaxed rules, the plant couldn't keep the dust under control.

Eight years later, in 1957, the plant was replaced by a larger one 10 miles away near Elmore.

Under government contract, Brush Beryllium built, owned, and operated the plant. In return, the government agreed to buy 50 tons of beryllium over five years. The AEC signed a similar contract with the Beryllium Corporation for a plant outside Hazleton, Pa.

When Gloria Gorka (about 2 years old above) began having difficulty breathing, her parents thought she was just having trouble getting over the measles. But scientists concluded she had contracted beryllium disease, caused by air pollution from a beryllium plant. Gloria died at age 7.

Both contracts had a health clause: If dust levels were consistently high, the government could close the plants.

Again, workers were overexposed throughout the 1950s and 1960s, industry and government records show. Dust counts at Elmore were regularly five times too high; some levels at Hazleton were 4,000 times over the limit.

Yet the Elmore plant was never shut, and the Hazleton plant was closed only once for about a month, according to a deposition by Mr. Powers, the former government and industry official.

The beryllium companies tried to meet the safety limit but to no avail. A Brush doctor blamed the failure on production demands, "triggered primarily by the space program."

One Brush document says every time the government considered closing the Elmore plant, "the Navy and AEC weapons people objected because they needed the metal for nuclear weapons and Polaris [missile] parts."

AEC officials, correspondence shows, weren't sure what to do about the high exposures.

One official wrote that better equipment had been suggested, but "this would increase the cost of beryllium by ten times," and "the plants would have to be shut down and rebuilt."

"The extra cost would be undesirable, but the latter factor is unacceptable because of AEC need for the metal."

Still, as bad as the dust counts were, they were improving and the disease rate appeared to be dropping. In fact, some officials thought the exposure rules might be too strict.

In 1960, a dozen AEC officials met to discuss the issue. They concluded that the plants, dangerous or not, must remain open, minutes of the meeting show.

"The [government] cannot stand for a cessation of production," one official stated.

That official was Martin Powers, in charge of buying beryllium for the AEC. But he was also responsible for ensuring that the beryllium plants were not overexposing workers.

Four months after this meeting, Mr. Powers left the government to work for one of the firms he had been responsible for monitoring: Brush Beryllium.

He would spend the next 26 years as a top executive with the company, often handling the government contracts and overseeing the health and safety program.

Today, Mr. Powers, 77, is retired from Brush but remains a paid company consultant. The government, he says, didn't know for sure that workers were going to be harmed by the overexposures. But he acknowledges the AEC was taking a risk that they might.

"I think there were certainly cases where you might have allowed marginal activities to exist hoping - but not really knowing - that they were going to be all right."

He says pressure on the AEC to keep plants running was enormous. He recalls receiving a phone call from an admiral who was livid about AEC plans to phase out a plant.

"This admiral called me and said, 'You will not shut that goddamn plant down. What are you, out of your goddamn-picking mind? I've got submarines out there. We need missiles.' "

Mr. Powers says he didn't agree with some government decisions. He says that the AEC for one or two years, about 1949 and 1950, insisted that Brush not put warning labels on beryllium products shipped to AEC facilities because it didn't want to alarm workers there.

Officials who made that decision, he says, "just didn't apparently feel it was their province to worry about the health issues."

Numerous workers would eventually develop beryllium disease after being overexposed in the 1950s and 1960s.

Among them: Gary Renwand, an Oak Harbor, O., resident who worked 35 years at Brush's Elmore plant.

Company records show that he was frequently exposed to high levels of dust - some amounts five times the safety limit.

Now, he is often in and out of St. Charles Mercy Hospital, battling heart and lung problems related to his disease. On one such day, he sits up in bed and recalls making beryllium re-entry shields for space capsules and watching the capsules on TV careen back to Earth.

"I thought, 'Hey, we made that shield.' And I was proud. I was part of this. A new era."

He forces a laugh.

"Young and dumb," he says.

Since the 1940's, the government has wrestled with the problem of how to balance the health dangers of beryllium production with its need for the metal for weapons and the space program.

'In the work of the Atomic Energy Commission, beryllium has unique properties which preclude the possibility of substituting some other material for it. Unless the experts change their mind as to its importance, the AEC appears to be stuck with beryllium and hence stuck with the public relations problems.'

- from a 1947 U.S. Atomic Energy Commission report titled 'Public Relations Problems in Connection With Occupational Diseases in the Beryllium Industry'

'The procurement of beryllium hydroxide from the Beryllium Corporation would be a complete reversal of policy concerning the production of beryllium products for the Commission in a plant which is medically unsound .... Although the Commission would probably not be legally responsible for damages, it cannot shirk its moral responsibility in this matter.'

- Wilbur Kelley, manager of the Atomic Energy Commission's New York office, to W.J. Williams, an AEC production director, on July 18, 1949.

'[The AEC will no longer bear] the responsibility for health conditions associated with the procurement and production of beryllium materials for the AEC, except where cost contracts were involved .... Mr. Williams then stated that further consideration of medical reasons would be dropped and that all consideration of the proposed arrangement with the Beryllium Corporation would be based strictly on economics.'

- Minutes of July 20, 1949, meeting of top AEC officials, including Mr. Kelley

'The Commission cannot stand for a cessation of production.'

- The Atomic Energy Commissioner's Martin Powers, at an AEC meeting Aug. 3, 1960, discussing whether plants overexposing workers should be shut down.

Safety plan fought; secret bargain cut

Only once in the last five decades has the U.S. government tried to tighten exposure limits.

That was in 1975, when OSHA proposed cutting the exposure limit in half - from 2 micrograms per cubic meter of air to 1.

The plan met tremendous opposition from the beryllium industry and U.S. weapons officials. Energy Secretary James Schlesinger warned that the plan might drive beryllium firms out of the metal business and cut off U.S. supplies.

"The loss of beryllium production capability would seriously impact our ability to develop and produce weapons for the nuclear stockpile and, consequently, adversely affect our national security," he wrote in 1978 to Labor Secretary Ray Marshall and Health, Education, and Welfare Secretary Joseph Califano, Jr.

Secretary Schlesinger wanted the scientific basis for the plan reviewed. Defense Secretary Harold Brown made a similar request.

So the plan was delayed until outside experts could review it. In the end, the experts concluded that the science behind the safety plan was indeed valid.

But the plan never went through.

One factor: In 1979, the Cabot Corp., now the owner of the beryllium plant outside Hazleton, Pa., quit making beryllium metal, leaving Brush Wellman as the sole U.S. supplier.

Almost immediately, the government cut a secret deal with Brush, according to government and industry records. Brush promised to continue to supply the Energy Department with beryllium for its weapons; in return, the agency promised to:

- Pay Brush a one-time 35 per cent price increase.

- Not develop other sources of beryllium.

- Try to persuade OSHA to drop its safety plan.

Within a few years, OSHA's safety plan died.

Throughout the fight, one thing remained constant: Workers continued to be overexposed.

Plants rarely inspected; metal's use not tracked

Today, more than 50 years after the disease was discovered, the rate of illness is higher than ever.

A study published in 1997 found that 1 in 11 workers at the 646-employee Elmore plant either have the disease or an abnormal blood test - a sign they may very well develop the illness.

And while dust counts at the Elmore plant are much improved, some remain over the legal limit, company records turned over in court cases show.

OSHA is responsible for inspecting the plant and making sure dust counts are low. If not, inspectors can write citations and issue fines.

But years have gone by without an inspector setting foot in the plant, OSHA records show.

When inspectors have found high dust counts, Brush Wellman has escaped penalties.

In fact, OSHA records show, Brush has never paid one cent for high exposures at any of its several facilities nationwide.

OSHA officials says there are simply not enough inspectors to regularly check the plants.

"We have about 2,000 compliance officers to cover 6 million work sites that employ more than 100 million workers," says OSHA spokesman Stephen Gaskill, who recently left the agency.

"So to say that we are spread thin is a severe understatement."

To make matters worse, no one knows what companies - from large corporations to small machine shops - are handling beryllium and whether safeguards are in place.

"There are beryllium-copper golf clubs now being used," says Dr. Peter Infante, OSHA's director of standards review. "Where are those being tooled and polished?"

Thousands of companies are believed to handle beryllium, but no one knows how many workers are potentially exposed. Estimates range widely, from 30,000 to 800,000.

Improvements, officials say, are in the works.

The Energy Department says it is spending millions to improve ventilation and air monitoring at government-owned sites. And Brush Wellman says it is improving equipment and work practices to reduce exposure.

Theresa Norgard, wife of disease victim Dave Norgard, of Manitou Beach, Mich., says she has heard such promises before. "Tired, worn-out phrases," she says. "Different time periods, same messages: 'Mistakes were made.

Now we're doing better. We're doing everything we can.' " Time and time again, she says, the government sacrificed the workers.

"They were just like pieces of equipment. They were disposable. They were dispensable. They weren't even seen as being human."