Legacy of Brown's holy war still debated

10/19/2009

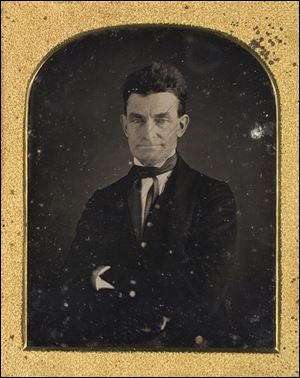

John Brown predicted the country would not 'purge' itself of slavery without bloodshed.

HARPERS FERRY, W.Va. - John Brown has spent 150 years locked in our national attic, the mad uncle no one wanted to acknowledge but over whose corpse soldiers would sing praises during the war he triggered.

The bearded messiah of the anti-slavery movement was hanged for his futile raid on the federal armory here. After 15 decades of neglect, historians are now praising, damning, and pondering Brown's legacy on the sesquicentennial of the Harpers Ferry raid.

In an era in which the term "domestic terrorist" now defines many of the actions for which Brown is lauded and loathed, historians want to sort out the meaning of the man. Some now call the Harpers Ferry raid in what was then Virginia the first shots of the Civil War; still others, a lesson in the complexities of history.

"Normal people don't produce social change," said Steven Mintz, a historian at Columbia University and an expert on pre-Civil War reformers. "Well-adjusted people who see trade-offs in life, they don't make social change happen. It's often people like Brown."

To the South, Brown was the half-lunatic harbinger of Northern aggression, the vanguard of a Republican Party they were sure would take their slaves and destroy their livelihoods.

In the North, towns divided over Brown. In Concord, Mass., philosopher Henry David Thoreau gave not one but two public speeches praising him as an avenging angel. Nathaniel Hawthorne declared, "Nobody was ever more justly hanged."

Brown's body still lies a-moulderin' in the grave in upstate New York, where he confounded even other abolitionists by treating freed slaves as social equals. A flesh-and-bones triptych of the 19th century, Brown coursed from New England to Kansas to Virginia, brushing shoulders with luminaries. With a bounty on his head after a broadsword massacre in Pottawatomie Creek, Kan., in 1856, he holed up in the home of a Boston judge. He met Ralph Waldo Emerson and Thoreau, conferred with Frederick Douglass. At Harpers Ferry he fought Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. John Wilkes Booth attended his hanging.

The bare outlines of Brown's life reflect the shifts of the first half of the 19th century and the deeply ingrained religious fervor that informed almost every aspect of civil life in that time.

"You can't understand John Brown at Harpers Ferry with-out understanding his religious views," said Stephen B. Oates, a University of Massachusetts professor who spent 40 years researching the man.

Brown was an old-line Calvinist, a tradition passed from his father, Owen.

"A Calvinist believes in an activist God, that God inserts his hand and directs human affairs," Mr. Oates said. Brown felt that hand in his early years, when he saw a slave boy beaten.

Born in 1800 in Torrington, Conn., he moved with his family to the Ohio frontier, living briefly in Hudson. He married Dianthe Lusk in 1820 and six years later, moved her and their children to the virgin forests of Crawford County, Pennsylvania. He opened a tannery, farmed, became the first postmaster of New Richmond, opened a school, and helped found a church in Guys Mills. It was the longest time he ever lived in one place and the time of his life about which historians know the least.

Brown's son, Frederick, died in 1832 at 4. Two years later, Dianthe Brown died in labor.

Donna Coburn lives on the New Richmond property, where Frederick and Dianthe's graves sit on a hillside. She sometimes finds herself escorting pilgrims.

"He just kind of captures people," Mrs. Coburn said. "Whether you're pro or anti-John Brown, he absolutely captures people."

By 1837, after Dianthe's death, Brown married again - a 16-year-old girl named Mary Day. She cared for Brown's remaining five children and bore him 13.

Also that year, a crusading, anti-slavery newspaper editor, Elijah P. Lovejoy, was murdered by a mob. At a memorial service in Ohio, Brown raised his hand and, as a startled crowd looked on, vowed to dedicate his life to slavery's destruction.

Brown, now a leading figure in the abolition movement, was living in North Elba in New York, on acreage set aside by Gerrit Smith, a wealthy social reformer. Brown lived alongside freed slaves, treating them as social equals. At the time, most abolitionists wanted slavery stopped but did not consider blacks social equals of whites.

Brown could have ended his days as a religious abolitionist, a cog in the Underground Railroad, but for a summons from his sons. They had settled in Kansas, and Kansas was bleeding.

The new territory was in the throes of a battle between free-state abolitionists and pro-slavery "border ruffians" who threatened free-state settlers.

When Brown arrived, he brought provisions, rifles, broadswords, and a flowing white beard.

Brown learned of an attack by pro-slavery men on the free-state town of Lawrence. After that came news that abolitionist Sen. Charles Sumner had been beaten nearly to death on the Senate floor. On May 24, Brown led his sons and followers in a nighttime raid on homes of five pro-slavery settlers. At one house, they dragged a father and two of his sons into the woods and hacked them to death with the broadswords.

"How much violence he personally committed, we don't know," said David Reynolds, a professor at the City University of New York and author of John Brown: Abolitionist.

Brown traveled to New England, where he was the toast of abolitionist society. "He moved in New England and New York social circles even though he was a wanted man," said Dennis Frye, a historian with the National Park Service at Harpers Ferry. "He had a price on his head from the United States government, but it didn't stop John Brown from going from church to church, meeting from person to person."

It was on those trips that Brown connected with six leading figures of the abolition movement, men who would finance his plans to create not an underground railroad, but an armed highway on which to move slaves along the ridge of mountains from Alabama to New York.

There were 100,000 rifles at the federal armory in Harpers Ferry, Va. He intended to have them.

While popular history has Brown trying to start a slave insurrection, many historians point to his plans for armed encampments along the Alleghenies through which slaves could be moved to freedom.

With money from the Secret Six - his abolitionist backers - he had 900 pikes made at a forge. He set up camp at a Maryland farmhouse, trimming his beard and calling himself Isaac Smith. The plan was simple, and spectacularly wrong: Seize the armory, commandeer a few thousand firearms, and wait for word to reach slaves. He was convinced they would flock to his side for a trek into the mountains.

On a Sunday night in October, 1859, Brown, who held the Sabbath so sacrosanct he would not receive visitors on it, marched into Harpers Ferry. He had 18 men, including several freed slaves and several of his sons.

That day, Hayward Shepherd, a baggage handler, ventured out to see why the train into town had stopped. In the darkness, Brown's forces shot Shepherd, a free black man. Brown's soldiers brought in slave owners as hostages, including a great-grandnephew of George Washington.

Later, they shot down Fontaine Beckham, the town's much-loved mayor, as he investigated the ruckus. As the siege wore on, Brown moved everyone to a small firehouse on the arsenal grounds.

He hoped to trade the hostages for free passage into the mountains. Brown, Mr. Frye said, expected some of the 18,000 slaves in the six-county Harpers Ferry area to come to his side.

By the middle of the next day, U.S. troops, under the command of then-Col. Robert E. Lee, arrived. They called for surrender. None came. At day's end, 16 men, including two of Brown's sons, were dead.

The battle at Harpers Ferry galvanized the South. Brown used the month between capture and trial to give unapologetic interviews and send dispatches embracing both his deed and likely fate.

Sentenced to die, he electrified the nation with his oration.

"I believe that to have interfered as I have done - as I have always freely admitted I have done - in behalf of His despised poor, was not wrong, but right. Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments I submit; so let it be done!"

Secessionist firebrand Edmund Ruffin of South Carolina had one of Brown's pikes sent to each Southern governor to show the horrors that awaited them should the North, under the newly formed Republican Party, have its way.

Brown, in fact, thought little of the Republicans, and Abraham Lincoln, the party standard-bearer, felt the same of Brown. In one of a succession of ironies, Brown's actions helped Lincoln win the election.

"Lincoln didn't want violence at all," Mr. Reynolds said. "The only reason it helps Lincoln is that it solidifies the Southern secessionist vote against the North, so it splits the parties into four separate parties."

Lincoln secured the presidency with a plurality. The South seceded, and Fort Sumter fell.

On Dec. 2, 1859, Brown rode four blocks atop the pine box that would be his casket to a square in Charles Town, Va., the Jefferson County seat. Thousands of troops ringed the area to prevent rescue attempts.

Brown reached into his favorite book of the Bible, Hebrews: "I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood."

Brown's hanging served his own purposes as much as it did the South's. A martyr, his name was invoked throughout the war. A squad of Massachusetts volunteers, to tease a fellow soldier who shared his name, sang of John Brown's body. The ditty was picked up by other soldiers who imagined singing about the hero of Harpers Ferry.

By war's end, the song was a campfire standard. It became the title of a poem by Stephen Vincent Benet.

Yet, in ensuing years, singing John Brown's praises became less and less fashionable. His raid, his uniquely close friendships with freed slaves, the hacking violence of the Pottawatomie raid, and the seeming madness of his behavior at Harpers Ferry, made him more a curiosity of the era than the pivotal figure Mr. Oates later found him to be.

The debate never quite settled.

At the Jefferson County Courthouse in nearby Charles Town, Carmen Creamer, president of the county historical society, put up photographs last week for the anniversary. It took a jury of 12 men, seven of them slave owners, almost no time to convict Brown. Today, it takes locals much longer to assess the man their forebears hanged. "It depends on who you ask," she said of Brown's legacy here. "He did take the law into his own hands. There were innocent people killed. Ironically, one of the first people to die in the raid was a black man."

Others say his purpose justified his actions.

"If you want to believe that he was mad, I'm not going to change your mind," said Mrs. Coburn, who tends the old Brown homestead in Pennsylvania. "I personally believe that he was chosen to do this great work. He did exactly what he was instructed by a much higher power than you or I."

Block News Alliance consists of The Blade and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Dennis B. Roddy is a reporter for the Post-Gazette.

Contact Dennis B. Roddy at:

droddy@post-gazette.com

or 412-263-1965.