Pentagon site offers lessons for the living

9/11/2011

Maj. Tevye Yoblick spends a quiet moment at dawn at the Pentagon Memorial. The memorial includes an illuminated bench for each victim of the attack on the U.S. Defense Department's headquarters.

Washington Post

Maj. Tevye Yoblick spends a quiet moment at dawn at the Pentagon Memorial. The memorial includes an illuminated bench for each victim of the attack on the U.S. Defense Department's headquarters.

W ASHINGTON -- Nearly 10 years on, airplanes still appear in the distance, vaguely at first, then clearer, then louder, then cringingly closer, wailing past the Pentagon.

Truckers still grind gears on State Rt. 27, commuters still honk and skid to rubber-burning stops in the clotted traffic of Arlington, Va.

But the human ear possesses special gifts. Somehow, in that two-acre plot of ground called the Pentagon Memorial, the ear can filter out all that noise and latch onto the sound of peace. It gurgles in the bubbling pools beneath 184 benches, the symbols of 184 lives lost on that day in 2001. Close your eyes, and listen to the water. Peace.

And then it stops.

Stops cold.

Does it every day.

Every day at 9:37 a.m.

One minute.

The pause feels like a challenge, a subtle admonition, jarring you, nudging you to think about what happened here at that very moment on a sunny morning in 2001 when a Boeing 757 turned into a weapon of mass destruction.

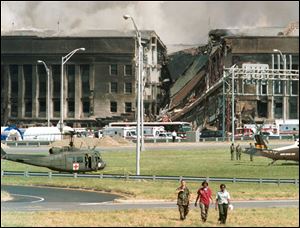

Three rescue workers walk away from the crash site at the Pentagon in Arlington, Va., in this Sept. 11, 2001, file photo.

In its three-year life, this space -- the first national Sept. 11 memorial -- has become a place for the tourist and the mourner who isn't intimidated by logistics. It is "not easy to get to," said Thomas Heidenberger, a retired airline pilot whose wife, Michele, was a flight attendant aboard the plane that slammed into the Pentagon at more than 500 mph.

Most visitors pile out of subway trains on the opposite side of the Pentagon and snake through parking lots, walking past one sign after another warning them against taking photos, a prohibition that ends when they arrive at the memorial. It also has become a destination for school groups. Open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, the site draws about half a million people each year, memorial officials say.

The memorial makes the visitor work to figure it out. It is far from a literal expression, not like the nearby Iwo Jima Memorial, which explains everything in a glance. Instead, it's an abstraction, pushing visitors to sort out its meaning and decide how to relate to it.

A group of teenagers was here one day recently, advancing tentatively through the thicket of benches. Three boys plopped onto a cantilevered bench, pulled out their water bottles, and placed them on the granite surface.

"It's a cemetery!" one of the girls screamed, her face reddening, every inch of her tensing. "Not a table!"

Lisa Leonard, a retired Army colonel who volunteers as a docent, has heard it before. Once it was German tourists. They thought it would be disrespectful to sit on the benches. "But it's not a cemetery," Ms. Leonard told them. Not a cemetery at all. Go ahead and sit.

Ms. Leonard, who was working in the Pentagon on Sept. 11, 2001, likes to scramble into the planting bed that rings the memorial and pull back the fronds to show visitors the top of a simple, unadorned concrete wall. It's three inches above ground level -- one inch for each year of the too-short life of Dana Falkenberg, a passenger on American Airlines Flight 77, the youngest victim of the terrorist attack on the Pentagon. The wall rises in step with the ages of the victims, Ms. Leonard will say, cresting at 71 inches to honor John Yamnicky, a retired Navy captain who was on the same plane.

Mr. Heidenberger, who was one of the original directors of the fund that created the $22 million memorial, keeps finding serendipity amid the symbolism. The memorial benches are organized in rows corresponding to the years the victims were born. Mr. Heidenberger noticed that his wife, coincidentally, was born in the same year, 1949, as Charles Burlingame, the captain of Flight 77. A captain always sits at the head of the plane, Mr. Heidenberger said one afternoon on the phone, and it just so happens that Mr. Burlingame is at the head of his wife's row. It seems fitting.

So does the placement of the benches commemorating the Falkenberg family. Mr. Heidenberger noticed that Dana, the 3-year-old, is honored next to her sister, Zoe, whose bench is in the next row across from Dana's, even though they were five years apart. Mr. Heidenberger also noticed that the benches honoring Zoe's and Dana's parents, Charles Falkenberg and Leslie Whittington, also ended up directly across from each other because he was born in 1956 and she in 1955.

Visitors take refuge from the heat in the slender, slotted shade of crape myrtles. Maples that might have sprouted large, leafy canopies were planted originally but did not thrive and had to be replaced. So, even in its youth, the memorial continues to evolve.

Maintenance crews pamper the space. A Salvadoran immigrant, Lucas Avilio Guzman, delicately removed gravel from the walkways that is ever finding its way into the shallow pools beneath each bench.

He was working in a hotel across the highway from the Pentagon when Flight 77 struck, and he fled the area on foot amid the chaos. He said he remembers the faces of the survivors he encountered. "They were nervous wrecks," he recalled. Now he manicures gravel in the space that honors the survivors. As he worked, his broom moved like a pendulum; it's as if he was tending a giant version of a Zen sand garden, pulling out gravel this week that will be back in the pools the next.

Mr. Guzman will arrive early today to spruce up his Zen garden for the arrival of dignitaries for an invitation-only ceremony commemorating the 10th anniversary of the terrorist attacks.

Mr. Heidenberger will wait until the crowd disperses.

He has been to the memorial at many times of day and under many circumstances, often stopping there after his 20-mile weekend bike rides. But he doesn't like to attend events there on the anniversary of the attack. That's a day he reserves for moments when well-intentioned speeches don't drown out the sound of burbling water. When he can be alone on a simple bench. Alone with his memories of Michele.