Modern day would please, anger author Charles Dickens

2/5/2012

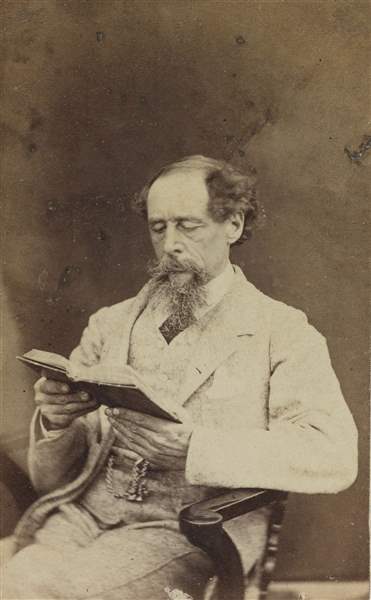

Charles Dickens, shown in 1863, remains best known perhaps for ‘A Christmas Carol.’ A manuscript signed in December, 1843, is in the Morgan Library in New York. The author ‘invented the cliffhanger,’ one scholar says.

morgan library & museum

Charles Dickens, shown in 1863, remains best known perhaps for ‘A Christmas Carol.’ A manuscript signed in December, 1843, is in the Morgan Library in New York. The author ‘invented the cliffhanger,’ one scholar says.

NEW YORK — The visitors have been coming at a steady trickle, reverent, bemused, squinting at the crabbed handwriting in the anguished letters from his American tour (“They will never leave me alone … I shake hands every day … with five or six hundred people”), the missives on mesmerism, philanthropy, storytelling, Christmas books, and his own manic energy.

Charles Dickens’ 200th birthday is Tuesday, and although the author of A Christmas Carol, Great Expectations, and A Tale of Two Cities obviously isn’t around to enjoy this tiny, exquisite exhibition at the Morgan Library & Museum in midtown Manhattan, he would no doubt be pleased at all the attention his birthday is getting — while simultaneously outraged that readers can now get his novels on Kindle at no charge.

A grand ceremony is planned for Tuesday at Westminster Abbey, where Mr. Dickens was buried in Poets’ Corner upon orders from his No. 1 fan, Queen Victoria. There’s a Twitter feed, mostly earnest but not always (“Breaking News: Times Literary Supplement accused of hacking Dickens’ telegrams”); a Dickens festival in China; a half marathon at Rice University in Houston (Mr. Dickens walked at least 8 to 10 miles a day), a full roster of PBS programming to add to more than 320 films made of his work, and the upward of 90 biographies published so far.

Still, is this anniversary marking a renaissance for Mr. Dickens or an elegy?

“Very few young people know Dickens and his work unless they read some of it in high school,” said Michael Helfand, an associate professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh who specializes in Victorian literature. “Young people don’t read long books any more, excepting Harry Potter.”

Perhaps, but “I go into the gallery frequently, and there are a good number of young people coming in to see the exhibition who weren’t brought in by their parents,” said Declan Kiely, curator at the Morgan Library, which possesses the world’s second-largest collection of Dickens manuscripts and letters after the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Off and running

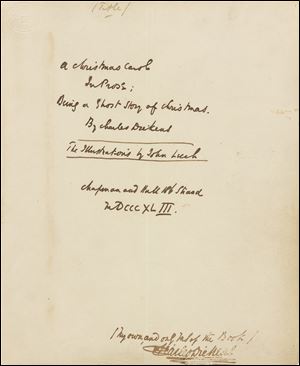

The text reads: A Christmas Carol in Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas Autograph manuscript signed, December 1843.

Born in 1812 in Portsmouth (where the buses are named for his novels) to a clerk in the British Navy, a young Dickens was sent to work in a blacking factory for five months while his father was in debtors’ prison. The experience scarred and shamed him for life and, perhaps, fueled his art.

A frustrated actor, he worked as a journalist before publishing The Pickwick Papers in 1836, which made him famous, and he was off and running. Oliver Twist was next (Queen Victoria pronounced it “excessively interesting” and urged her patrician prime minister, Lord Melbourne, to read it), and then a steady stream of novels, some written simultaneously.

His books were a sensation everywhere but were relentlessly pirated in America — prompting Mr. Dickens, the first literary celebrity, to become a lifelong crusader for international copyright laws. Obsessed with both writing and making money, he was a gifted merchandiser of his novels, which he churned out in pieces every month, stuffed with characters — benevolent, malevolent, magniloquent, or just hilarious.

Everyone read Mr. Dickens, from housewives to harness merchants to the financier J. Pierpont Morgan, “the way we all read the latest John Grisham or Stephen King today,” Mr. Kiely said.

John Jordan, director of the Dickens Project at the University of California at Santa Cruz, said, “Dickens was on the cutting edge of the new technology of his age, which was serial publication of novels in cheap monthly installments.” He noted that when Mr. Dickens wrote The Pickwick Papers, novels were published in three leatherbound volumes, called three-deckers, “which cost two weeks of a working man’s salary, so he started publishing in serial installments. He really invented the cliffhanger.”

Can’t wait to see what happens next on Downton Abbey? When Mr. Dickens began publishing The Old Curiosity Shop, now read mostly by scholars, suspense over the fate of the waifish Little Nell made the public frantic.

“Does Nell live?” American crowds purportedly shouted from the docks as the steamers came in from Britain bearing the latest installment of the novel (spoiler alert: she doesn’t, which so disgusted one Irish member of Parliament that he threw the book out of his train’s window).

Mr. Dickens wrote so graphically about Victorian London’s squalor — and yet so sentimentally about Christmas — that, along with “Scrooge” (miserly type), the word “Dickensian” has entered the lexicon signifying grotesque poverty, the grotesquely comic, or jolly, convivial holiday family gatherings complete with brandy rum punch and scampering children.

He was a man consumed. He wrote Bleak House, he said, “in a perpetual scald and boil” and would, after a particularly strenuous bout, call for a cold pail of water so he could plunge his head into it.

A dark side

What’s not to love?

Lots.

He idealized women in his fiction but treated his own wife, Catherine Hogarth, abominably and carried on a 19-year secret affair with actress Nelly Ternan, which began when she was 18 and he was 45. After he separated from Catherine, he banished her from the family home and prevented her from seeing their 10 children, whom he also resented because, he claimed, they lacked his own work ethic and intelligence and were a constant drain on his finances.

Still, he thrived. “All his characters are my personal friends,” declared Leo Tolstoy, and their names live on in trivia games and iPhone apps, if not on bookshelves: Dr. Marigold, Mr. Chops, Quilp, Wopsle, and The One Eyed Bagman.

It’s impossible to know how many people read him today because his works are no longer under copyright and are free on e-readers. Publishers are constantly reissuing his works and claim sales in the millions, fueled by hundreds of television and film adaptations.

“There’s always a sense that Dickens is out of fashion, but the books keep selling, keep their interest in some way,” said Fred Schwarzbach, a New York University professor, author of Dickens and the City, and president of the American Friends of the Charles Dickens Museum in London. “He is part of the world culture that doesn’t require an endorsement by educators and critics. People just keep reading him. I know I do, every holiday season, and the number of ads for A Christmas Carol suggests very powerfully that others do too.”

At the University of California at Santa Cruz, the Dickens Project, a multiuniversity research consortium, holds regular conferences in an attempt to keep the author fresh and relevant.

For years, it was funded by the state university system, but when California’s economy went into free fall, the money stopped flowing.

“We’re doing OK, just about breaking even, but we’re always asking for more, like Oliver Twist,” says Mr. Jordan. “He is absolutely contemporary, and he belongs in the 21st century.”

One can only imagine what Mr. Dickens would have made of the slums in Lagos or Mumbai (in fact, the BBC produced a modern-day adaptation of Martin Chuzzlewit called The Mumbai Chuzzlewits).

Salman Rushdie, born in India but educated in Britain, “said he was convinced from the moment he began reading that Mr. Dickens was an Indian novelist because the complexity, vitality, and ferment of 19th century London reminded him of that of India,” Mr. Jordan added.

One complaint, that Mr. Dickens’ characters are caricatures lacking in psychological realism, is an old one: Henry James, in an 1865 review in the Nation, called Mr. Dickens “the world’s greatest superficial novelist.” Mr. Helfand, the Pittsburgh professor, cited William Faulkner’s maxim that novels could be “small successes or great failures. Mr. Dickens’ are clearly in the latter category, great but with flaws.”

In the early 20th century, before George Orwell’s 1940 review resurrected him as a major social critic, there had been a reaction against Mr. Dickens “as too simple and sentimental, mainly based on snobbery and a belief that Henry James had defined what a really good novel had to be like,” Mr. Helfand said, “but both of those ideas have gone the way of all criticism — to the ash bins of history.”

American tour

Mr. Dickens seemed less than thrilled about some aspects of his 1842 tour of the United States, which included a journey through northwest Ohio as he traveled from Columbus to Sandusky.

From the Neil House in Columbus, which Mr. Dickens seemed to enjoy, his party rode by a stagecoach to Tiffin.

He described the road as a track through swamp and forest, much of it of tree trunks left to settle in a bog. The passengers in the coach were often thrown to its floor and flung at its sides as it lurched over the terrain.

“Still,” Mr. Dickens wrote, “the day was beautiful, the air delicious, and we were alone, with no tobacco spittle, or eternal prosy conversation about dollars and politics [the only two subjects they ever converse about, or can converse about] to bore us. We really enjoyed it; made a joke of being knocked about; and were quite merry.”

They spent the night in a log tavern in what was still considered Indian country. Mr. Dickens referred to the area as the Upper Sandusky, but other accounts pinpont it to McCutchenville on the Wyandot-Senaca county line. The tavern had bedbugs, doors that would not stay shut, and pigs wandering about outside.

They left after breakfast and arrived in Tiffin about noon, where they caught a train.

Mr. Dickens described the trip: “At 2 o’clock we took the railroad; the traveling on which was very slow, its construction being indifferent, and the ground wet and marshy; and arrived at Sandusky in time to dine that evening. We put up at a comfortable little hotel on the brink of Lake Erie, lay there that night, and had no choice but to wait there next day, until a steamboat bound for Buffalo appeared. The town, which was sluggish and uninteresting enough, was something like the back of an English watering-place out of season.”

Rough as his journey was through rural Ohio, many of Mr. Dickens’ opinions of the United States had been formed before he arrived in the area, which was one of the last legs of his journey before returning to England.

“It was that democratic culture he so admired, but everyone wanted to see him and have five minutes of conversation, but that brash New World approach to manners really shocked him and he could never get used to it,” Mr. Schwarzbach said.

In one letter, Mr. Dickens complains “I have hardly time, here, to dress — undress — and go to bed. I have no time whatever for exercise. You may suppose I have very little time for writing. This last consideration is the greatest annoyance I have.”

That was in 1842, when he was still relatively healthy, and many years of success lay ahead. But his second exhausting tour in 1868 (“Wherever I go, they play my books, with my name in big letters”) is believed to have contributed to his death at age 58 in 1870.

Future readers?

His birthday Tuesday may trigger a revival of readers, said Mr. Kiely of the Morgan Library, where the collection of Dickensiana has been growing ever since Mr. Morgan, back in 1890s, purchased the original manuscript of A Christmas Carol to go along with his Michelangelos, Raphaels, and Rembrandts.

“I’d like to think Dickens will be rediscovered, but the Internet has made too much of a claim on our children, who’d rather spend time on Facebook than put their faces in the pages of a Dickens novel,” Mr. Kiely said.

At the Penguin Bookshop in the Pittsburgh of Sewickley, Mr. Dickens is not a big seller.

“A lot of kids only come in and ask for Dickens when they’re assigned to read him in class,” said Kate Weiss-Duncan, the store manager. “I haven’t read him since high school. I think he’s an important writer, but I’m not surprised that people aren’t reading him.”

Yet there are encouraging signs that this emotionally extravagant, filmic storyteller, social reformer, and cultural icon may find his way into the lives of younger generations — if not in a book, at least on Netflix, the BBC, or even on a mobile phone App (the London Museum recently released one for iPhones called “Dickens: Dark London.”)

And thanks to repeated viewings of A Christmas Carol, Mr. Kiely’s 3-year-old twins can point to a photo of the author’s careworn, grizzled face, and say, “Narls Nickens.”

Blade staff contributed to this report. Block News Alliance consists of The Blade and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Mackenzie Carpenter is a staff writer for the Post-Gazette.

Contact Mackenzie Carpenter: mcarpenter@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1949.