Result of ‘40 census finally to be public

Access to be available on Internet in April

3/19/2012

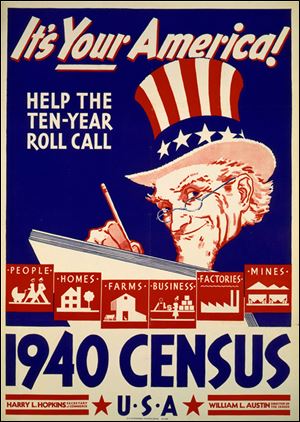

This poster was part of an unprecedented Census Bureau effort to encourage Americans to participate in the tabulation.

NEW YORK — It was a decade when tens of millions of people in the United States experienced mass unemployment and social upheaval as the nation clawed its way out of the Great Depression and rumblings of global war were heard from abroad.

Now intimate details of 132 million people who lived through the 1930s will be disclosed as the U.S. government releases the 1940 census April 2 to the public after 72 years of being kept confidential.

Access to the records will be free and open to anyone on the Internet — but they will not be searchable by name immediately.

For genealogists and family historians, the 1940 census release is the most important disclosure of information in a decade.

Scholars expect the records to help draw a more textured portrait of a transformational decade in American life.

Researchers might be able to follow the movement of refugees from war-torn Europe in the latter half of the 1930s, sketch out in more detail where 100,000 Japanese Americans interned during World War II were living before they were removed, and more fully trace the decades-long migration of blacks from the rural South to cities.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr., a Harvard University professor and scholar of black history who has promoted, through popular television shows, the tracing of family ancestry, said the release of the records will be a “great contribution to American society.”

Mr. Gates’ new PBS series, Finding Your Roots, is to begin Sunday.

He said the “gold mine” of 1940 records would add important layers of detail to census records dating to 1790.

Mr. Gates is scheduled to speak in Toledo May 3 as part of the Authors! Authors! lecture series.

“It’s such a rare gift,” he said of the public’s access to census records, “especially for people who believe that establishing their family trees is important for understanding their relationship to American democracy, the history of our country, and to a larger sense of themselves.”

More than 120,000 enumerators surveyed 132 million people for the Sixteenth Decennial Census. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 21 million of them are alive today in the United States and Puerto Rico.

The survey contained 34 questions directed at all households, plus 16 supplemental questions asked of 5 percent of the population.

New questions reflected the government’s intent to document the turbulent decade by generating data on homelessness, migration, widespread unemployment, irregular salaries, and fertility decline.

Some of the most contentious questions focused on personal income and were deemed so sensitive they were placed at the end of the survey. Fewer than 300,000 people opted to have their income responses sealed.

In part because of the need to overcome a growing reluctance by the American public to answer questionnaires and because of fears about some new questions, the bureau launched its biggest outreach and promotional campaign up to that time, according to records obtained at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park, N.Y.

The bureau opened its first division of public affairs to blanket the country with its message, reaching out to more than 10,000 publications and recruiting public officials, clergy, and business owners to promote it.

Movie studios were enlisted to encourage their film stars to participate. They included Cesar Romero, who later played the Joker in the Batman television series.

The bureau also hired the managing editor of “Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life” to galvanize support in the black community. But studies in the 1940s revealed undercounts, including 13 percent of draft-age black men.

In a first for the National Archives and Records Administration, the nation’s recordkeeper plans to post the entire census on the Internet, its biggest digitization effort to date.

Still, finding a name in the 3.8 million digitized images will not be as easy as a Google search: It could be at least six months after the release before a nationwide name index is created. Meanwhile, researchers will need an address to determine a census enumeration district in order to identify where someone lived and be able to browse the records.

Some experts said enthusiasm for the release could be dampened by the lack of a name index, especially for novices. “It may very well frustrate the newcomers,” said analyst Thomas Macentee.