Reporter on the scene recalls tragic day in Dallas

11/17/2013

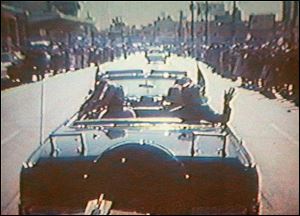

Footage taken by presidential aide Dave Powers and photographed from a television screen shows President John F. Kennedy, accompanied by his wife, Jacqueline, waving to the crowd in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963.

ASSASSINATION RECORDS REVIEW BOARD

Footage taken by presidential aide Dave Powers and photographed from a television screen shows President John F. Kennedy, accompanied by his wife, Jacqueline, waving to the crowd in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963.

DALLAS — Thirty-two newspaper and wire-service reporters, five radio and TV broadcasters, four magazine writers, and nine photographers and cameramen were traveling with President John F. Kennedy 50 years ago on Nov. 22, 1963, the day he was killed in Dallas.

I was one of the newspaper reporters, working for a quirky Dow Jones weekly called the National Observer.

Except for Marianne Means of the Hearst newspapers, we were all male, and all of us were white. Tom Wicker was there for the New York Times, David Broder for the Washington Post, Peter Lisagor for the Chicago Daily News, Alan Otten for the Wall Street Journal, Robert Donovan for the Los Angeles Times, Douglas Kiker for the New York Herald Tribune, and Jerry terHorst for the Detroit News.

RELATED: Remembering JFK's 1960 campaign stop in Toledo

RELATED: Air Force One a moving artifact then and now

RELATED: Limo that carried JFK on day of his assassination on display in Dearborn

I was making my second presidential trip. Most of the others were longtime veterans of these presidential cavalcades.

None of us could have guessed that this would be the biggest, and saddest, story we would ever cover.

My best source for what happened on that trip is, of course, the story I wrote on my Olivetti portable typewriter, most of it put together on the Pan Am press charter that took us back to Washington.

I stitched the rest together in my office from wire service reports, especially those banged out by the UPI’s amazing Merriman Smith.

I picked up the presidential party on Thursday in San Antonio. We moved on to Houston where President Kennedy boasted to an audience that the United States was going to launch what he said would be the biggest “payroll” in history.

Correction. “Payload” was what he meant. But, he said, recovering nicely, “It will be the largest payroll too.” The audience loved it.

We knew why we were in Texas. This was November, 1963, and the presidential election was a year away. Mr. Kennedy and his vice president, Lyndon B. Johnson, were trying to bring the party’s two warring factions into some kind of working relationship, at least until the votes were counted.

The conservative faction was led by Gov. John Connally; the liberal faction was led by Sen. Ralph Yarborough. They despised each other.

I had gone to Texas to write about the feud and make some kind of wild prediction on the Democrats’ chances of carrying Texas in 1964.

Late Thursday night, we took off from Houston for Fort Worth. All the city’s major buildings had been outlined by strings of yellow lights welcoming the presidential and vice presidential couples. I was amused at the time that the Johnsons were assigned the Texas Hotel’s most luxurious suite, at $100 a night. The Kennedys were assigned a smaller suite, at $75 a night. The Secret Service said they wanted it that way, but none of us, knowing Mr. Johnson as we did, quite believed it.

The president had been greeted by 100,000 Texans in San Antonio and another 200,000 in Houston. The senior correspondents passed the word to one another that maybe the ticket wasn’t doomed after all.

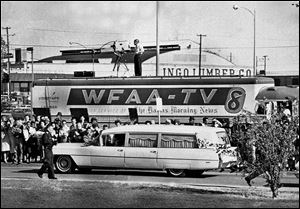

People line the street as the hearse bearing the body of President John F. Kennedy leaves Parkland Hospital in Dallas.

The next morning, Friday, the fateful day, crowds began gathering outside the hotel by 7 a.m., waiting patiently in a light rain.

At 8:50, they let out a big cheer as the president, hatless and coatless, emerged. He wore a two-button gray suit, a white shirt, a dark tie, black shoes. He spoke briefly, stressing the theme of national security in the space age and then went back inside the hotel.

He spoke to members of the Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce in one of the hotel’s banquet rooms, reminding his audience that his brother, Joseph Kennedy, Jr., the oldest of the Kennedy children, was killed while piloting a B-24 Liberator bomber, made in Fort Worth, on what amounted to a suicide mission in World War II.

After the speech, he and his motorcade made their way to Carswell Air Force Base. He boarded Air Force One for the short hop to Love Field in Dallas.

We had made the same short hop a little earlier in our own chartered Pan Am press plane. We were lined up with the plane’s crew on the tarmac when the president and the first lady came down the ramp. Mrs. Kennedy, wearing a raspberry pink suit, came down the ramp first.

Robert Caro, in his multi-volume biography of Mr. Johnson, says Mr. Kennedy stopped briefly as he came down the ramp to adjust his back brace.

Several hundred Texans were lined up behind the restraining ropes, and Mr. Kennedy, right hand extended, waded in to shake their hands. “Oh my,” one teenage girl said, “I’ll never wash my hands again.”

The motorcade

The motorcade was waiting for us. Cops on motorcycles were up front, followed by the president’s blue Lincoln Continental limousine, top down, District of Columbia license plate GG-300, flown to Texas by the Air Force. Mr. Kennedy was in the right rear seat, Mrs. Kennedy next to him. The two jump seats were occupied by Governor Connally and his wife, Nellie. In front were the driver and a Secret Service agent.

Next in line was a big lumbering vehicle called the Queen Mary by reporters and filled with Secret Service agents. Behind it was a Lincoln convertible carrying Vice President Johnson and his wife, Lady Bird, and a stubborn Senator Yarborough, who had refused invitations to ride with Governor Connally.

I was in the first press bus, perhaps 200 yards behind the president’s limousine. Another bus, for the local press, was just behind us.

The motorcade moved south along Lemmon Avenue, a residential part of town, turned into Turtle Creek Boulevard, turned again into Harwood Street. Crowds began to gather as we approached downtown. When we turned into Main Street, they were lined up five or six deep. Most of us hadn’t expected this kind of enthusiasm.

We passed the famous Neiman-Marcus department store and began bearing right at the triple underpass, where Main Street ends and the Stemmons Freeway begins. At that point, we were only a few minutes away from our destination, the Trade Mart, where Mr. Kennedy was scheduled to talk to many of Texas’s leading industrialists and businessmen.

Shots fired

I then heard two sharp reports, with only a pause of two or three seconds between. (The Warren Commission said three shots were fired. I might have missed the first one.)

Looking out the window on my right, I saw a woman sobbing on the grass along the freeway curbing. A police officer, standing near the curb, had covered his face with his hands. A motorcycle police officer gunned across the curb and up the grassy slope. I saw a black man on his knees on the grass, two little children at his side. He was beating his fists into the grass in obvious anguish.

Some reporters on the bus speculated that the reports they had heard were backfires. I was no expert, but I had spent time in the Marines, and I had no doubt we had heard gunshots.

The motorcade began picking up speed. Everybody now realized shots had been fired; some of the reporters wanted the driver to stop, so they could get off. He wouldn’t; the bus kept moving.

We pulled into a rear entrance at the Trade Mart, and piled out of the bus. We ran into the auditorium, sped past startled Texans midway through lunch, and made our way, chaotically, to a press room that had been set up on the fourth floor. No one staffing the press room had any idea what had happened, so we turned around and bolted back to the ground floor, where we picked up rumors that the president had been wounded and had been taken to the hospital. He was dead, somebody said. Governor Connally was wounded.

By the time we piled back aboard our bus, word had spread that the president and the governor had been taken to Parkland Memorial. Take us there, someone told the driver.

He refused, saying no one had given him orders to do that. A burly TV technician started pulling him out of his chair, saying he’d drive the bus himself. The driver relented, and we pulled away for the hospital.

At the hospital

The first person I saw when we arrived at Parkland was Senator Yarborough, standing alone in the driveway that leads to the “ambulance only” entrance. The senator was immediately surrounded by the press.

He told us he thought he had heard three shots. A Secret Service agent in his car shouted, “Get down! get down! get down!” The shots, the senator said, “seemed to be off to the rear, to the right somewhere. It was like someone was shooting behind us.”

“They [the president’s limousine] took off at a very high rate of speed for the hospital. We knew something must be terribly wrong.”

The senator said he couldn’t see the president because the Secret Service agents in the car ahead of him blocked his view. But he said he did see one of the agents in the president’s limousine waving a submachine gun. Another agent, he said, “was beating on the car with his fist — in anger and desperation and fear.”

Almost all the way to the hospital, he told us, “you could smell the gunpowder.”

“They [the president and the governor] were put on stretchers and carried inside. It is,” and his voice began to break, “too horrible to describe. They were seriously hurt,” he whispered. “The injuries to both of them are very grave. This is a deed of horror, a deed that is indescribable.”

He was asked if he had seen the extent of the president’s wounds. He had, and he knew they were fatal, but he couldn’t bring himself to say so. “Please, please,” he pleaded, “no more, no more.” In tears, he walked away.

We also talked to Charles Hodges, a Dallas high school student, standing in the driveway. He said he had been clinging to a street sign as the president’s limousine raced by on its way to the hospital. “I could see Jackie,” he said. “She was lying on top of the president, as if to shield him.”

The president and Governor Connally were taken into the hospital at 12:38 p.m., only seven minutes after the shooting.

‘He’s dead’

It wasn’t much later that we saw two priests leaving the hospital. “Is the president dead?” a reporter asked. “He’s dead all right,” one of the priests, the Rev. Oscar Huber, pastor of Holy Trinity Church, replied. He said he had given Mr. Kennedy the final rites.

Soon after that, a press room was set up in what was normally a nurses’ classroom on the ground floor of the hospital.

For what seemed like the longest time, the only noise in the room was the scuffling of feet. Occasionally, a reporter — Henry Brandon of the Sunday Times of London was one — would whisper, “God, god.”

Pierre Salinger, the president’s press secretary, wasn’t with Mr. Kennedy in Texas. He was with members of the cabinet in Tokyo. Andrew Hatcher, the No. 2 press secretary, was in Washington.

Malcolm Kilduff, the third-ranking press secretary, arrived in the press room at 1:30 p.m.

“President Kennedy,” he said, “died at approximately 1 o’clock central standard time here in Dallas of a gunshot wound in the brain. I have no other details regarding the assassination of the president.”

But he did have more details. Governor Connally, he said, had been shot too but was alive. Vice President Johnson — now President Johnson — had left the hospital, but “for reasons of security I can’t discuss his present whereabouts.”

The governor’s press secretary, Bill Stinson, told us that Mr. Connally had been shot in the chest.” His right wrist had been struck too and a small bone fractured.

Doctors appeared in the press room and explained as best they could what they had observed and done in the emergency room. It meant very little to me, then or now. The sad fact was the president had been killed by an assassin — I have always believed it was a lone gunman — and nothing could change that.

It was about 2 p.m. when I remembered I had left something behind in the press bus I thought I needed — a new notebook, perhaps. I passed several Dallas and state police cars, all of them with their radios blaring. They seemed most interested in hearing how the governor was doing.

I think, but I can’t be certain, that I was the only reporter who saw the casket containing the body of the fallen president being placed in a beige Cadillac hearse. Mrs. Kennedy, no longer wearing her hat, the raspberry suit and the stocking on her left leg streaked with blood, emerged from a side door. Walking without support, she climbed into the back of the hearse, talking a seat near the casket. Minutes earlier, I learned later, she had removed her wedding ring and slipped it into her husband’s hand. The hearse moved slowly away. I had no idea at the time exactly where it was going. Love Field, of course, for the long, sad flight back to Washington.

A new president

We had worried early on that no one was with Mr. Johnson, now the president of the United States. But by the time he reached Love Field and boarded Air Force One, the press pool — a small group of reporters that is supposed to accompany the president everywhere — was on the job. One of them, Sid Davis of Westinghouse Broadcasting, stayed behind to tell us what had taken place on the big blue-and-white Boeing 707 before take-off.

A federal judge, Sarah Hughes, had been fetched to administer the simple oath of office, making it official that Lyndon Baines Johnson was now the 36th president.

By the time we reached Washington, the wire services were reporting that Mr. Kennedy’s assassin was 24-year-old Lee Harvey Oswald, who, from a sixth-floor window of the seven-story Texas School Book Depository building, had taken careful aim with a mail-order Italian bolt-action rifle and gunned down the president.

A final quote

I ended my story by quoting from the speech Jack Kennedy would have given on Nov. 22, 1963, at the Trade Mart in Dallas, Texas. I think it’s worth repeating.

“We, in this country, in this generation, are — by destiny rather than by choice — the watchmen on the walls of world freedom. We ask, therefore, that we may be worthy of our power and responsibility — that we may exercise our strength with wisdom and restraint — and that we may achieve in our time and for all time the ancient vision of ‘peace on earth, good will toward men.’

“That must always be our goal — and the righteousness of our cause must always underlie our strength. For as was written long ago, ‘Except the Lord keep the city, the watchmen waketh but in vain.’”

The Block News Alliance consists of The Blade and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.