Newton Steel strike focused eyes of the nation on Monroe Labor museum to commemorate 70th anniversary

5/9/2007

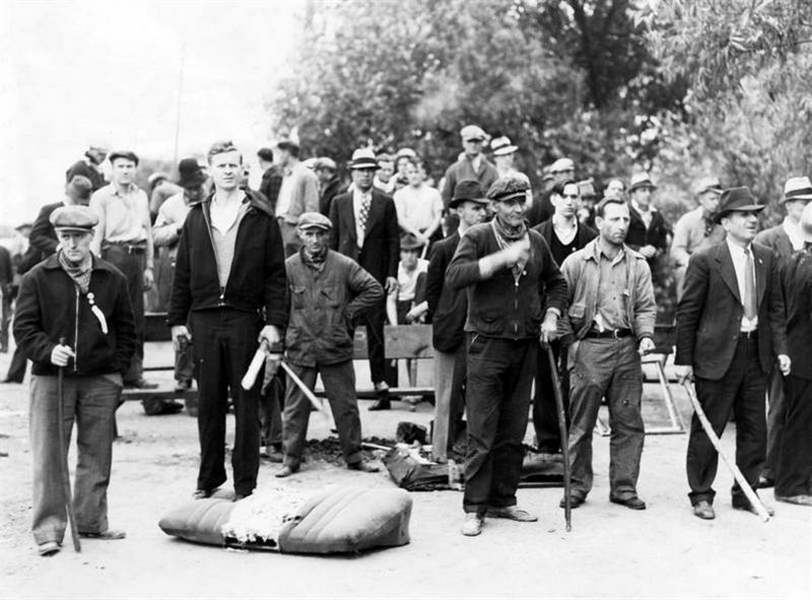

A picket line formed at one of the entrances to Newton Steel in 1937.

A picket line formed at one of the entrances to Newton Steel in 1937.

MONROE - The Battle of the River Raisin and subsequent Massacre of the River Raisin took place in January, 1813, on a field now enshrined as one of Monroe's most prominent ties to history.

But 125 years after U.S. troops used the famous rallying cry - "Remember the Raisin!" - another seminal and similarly dreadful event consecrated the same exact ground.

The Monroe County Labor History Museum tomorrow will open its exhibit to honor the 70th anniversary of the Newton Steel strike.

The violence that ensued garnered national attention because, for a moment, the little city of Monroe embodied larger tensions over union organization.

Those who opposed the strike overturned striker's autos. The picketers gave way.

In 1936, U.S. Steel unionized and the Workers Organizing Committee of the Congress of Industrial Organizations thought the next logical step was to organize "Little Steel" to follow suit.

When smaller steel makers, including Republic Steel, refused to follow its lead, a strike was called.

Hundreds of union sympathizers demonstrated in Chicago on March, 30, 1937. Ten demonstrators were killed by police bullets during the "Little Steel Strike" - what is now also known as the Memorial Day Massacre.

So the strike against Monroe's Newton Steel, a subsidiary of Republic Steel, was an extension of the larger strike against Little Steel as a whole.

After the Michigan National Guard arrived at the site, there was peace.

The strike consumed Monroe - 1,350 of its 18,000 residents worked in the plant - and eventually it enthralled the nation.

According to James E. DeVries, a professor of history at Monroe County Community College who has studied the strike, at least 1,000 spectators came to Monroe to see what would unfold.

"Kids were perched in apple trees, people came on boats to look. The New York Times was there," Mr. DeVries said.

But like in Chicago, the strike in Monroe did not work in the union's favor.

The persons who came to Monroe to organize strikers only convinced about 120 people to join.

Republic Steel organized a company union of about 800 members. The mayor of Monroe, Daniel Knaggs, took a vote and determined that more workers wanted to go to work than wanted to strike, so he created a force of 200 special police armed with clubs and tear gas to protect the workers.

On June 10, violence escalated, tear gas was thrown, clubs were used against strikers, and the police eventually busted the picket line and strikers fled.

After things got out of hand, the city began to worry that the 20,000 United Auto Workers in Flint and Pontiac, Mich., might come down to Monroe and take over the town and reopen the picket lines.

So Mayor Knaggs created a citizens battalion, deputizing 600 people and giving them food and clubs.

Many of them came out with their own shotguns and deer rifles to guard Monroe.

On Sunday, June 13, the National Guard and the Michigan State Police came to Monroe, and with their arrival, peaceful picketing eventually was arranged, tensions diminished, and workers went back to work a few days later.

A union was not finally established at Newton Steel until after World War II, when Monroe, like many other regions throughout postwar America, became a strong labor town.

Mr. DeVries said it was later revealed that Republic Steel had paid the mayor to bust the strike and hire the vigilantes who beat the strikers and threw their cars into the river.

He said records reveal that the steel company supplied the vigilantes with the tear gas and clubs.

"What happened in Monroe set back the labor movement that had been on a roll," Mr. DeVries said.

"It was Monroe that could be used [by Republic], because it was small enough that the people felt threatened."

But the exhibit that opens tomorrow will relive that moment, when once again Monroe found itself as a focal point, a rally cry, for change.

"At that time, during the strike, all eyes were on Monroe," Mr. DeVries said. "There are not many times when a small community is the focus of national attention."

The Newton Steel Strike exhibit is the museum's first self-produced exhibit since its 2005 opening.

A historical marker will be dedicated at 4 p.m. tomorrow at the River Raisin Battlefield Center, 1403 East Elm Ave.

A three-minute newsreel clip that was taken during the strike will be shown in the center.

At 5:30 p.m., the exhibit will be unveiled at the museum, 41 West Front St.

The museum is open from 9 a.m. to 11 a.m. and 1:30 p.m. to 3:30 p.m. on weekdays and by appointment on weekends.