OSU helps athletes clear hurdles of locker-room stigma

Gay track star finds support as university addresses bias

5/12/2013

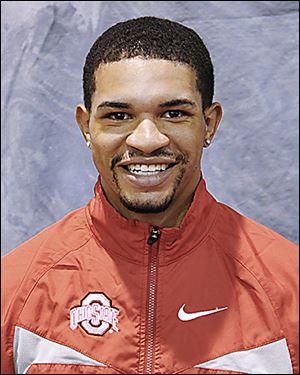

OSU’s Derrick Anderson focuses on confronting the hurdles he faces on and off the field of competition.

OSU’s Derrick Anderson focuses on confronting the hurdles he faces on and off the field of competition.

COLUMBUS — He was a rising football star in a Texas town where Friday nights were everything.

Derrick Anderson had the instincts, the speed of a district champion hurdler, and as a cousin of Green Bay Packers tight end Jermichael Finley, the pedigree. As a sophomore starting safety at Class 5A Mansfield Timberview in Arlington, letters already were arriving from interested colleges, including Missouri and Texas A&M.

“I knew my talent would get me there in football,” Anderson said. “I just didn’t know personally if I could do it.”

Anderson planned to reveal in college what he had kept hidden from his classmates in high school.

He was gay.

Was big-time college football ready for a player to come out? Anderson decided no, and after tearing up his knee late in his sophomore season, he walked away from the sport to focus solely on running.

“I just decided, I love track as well, so I’m glad I have a second sport to go to college with,” he said. “It was so scary.”

Anderson has no regrets. Today, he is an openly gay hurdler on the Ohio State track and field team — a symbol of the enduring fear of the unknown among closeted athletes in the four major team sports but also a banner of progress at one of the nation’s most forward-looking athletic departments.

Anderson and Ohio State are part of a mushrooming conversation as the sports world makes its greatest leaps yet to foster an atmosphere of inclusion.

Times are changing.

Derrick Anderson says he grew tired of the double life of being a closeted gay athlete.

NBA center Jason Collins kicked down one of the last barriers in sports recently when he became the first active player in one of the four major American professional leagues to come out; NFL linebacker Brendon Ayanbadejo has repeatedly said a handful of football players is poised to follow suit, and the NHL last month announced a partnership with the You Can Play Project, declaring its aim to be “the most inclusive professional sports league in the world.”

Perhaps no single major program or franchise is taking a more high-profile stand against homophobia in sports than Ohio State.

Taking a stand

Led by an athletic director for whom the message of acceptance is freighted with deep personal meaning, the school has loudly addressed a topic often touched only with fine-print, anti-discrimination policies.

Ohio State’s efforts range from the Buckeyes men’s hockey team in February becoming the first college program to host a Gay Pride night to repeated departmentwide reminders that, as OSU men’s track and field coach Ed Beathea said, “discrimination has no place.”

In a meeting with Ohio State’s head coaches last month, Athletic Director Gene Smith showed the footage of former Rutgers basketball coach Mike Rice hitting, kicking, and berating players with anti-gay slurs such as “faggot” and “fairy.” Rice was fired April 3 after the practice video became public.

“I talked about his language being just as offensive as what he was doing physically, and how that’s unacceptable at any level,” Smith told The Blade. “I’ve been that way always.”

Cyd Zeigler, a co-founder of Outsports.com, the leading outlet for news on gay athletes, lauded Ohio State’s head-on openness.

“To see a big program like Ohio State do this is really great,” Ziegler said. “There just aren’t many schools going to these lengths, and there aren’t many that will say the kinds of things that Smith says.”

Still, for all the progress, a towering hurdle remains.

Anderson knows of only one male athlete at OSU who has come out to his teammates. Himself.

He also knows he can’t be alone.

An empathetic leader

The man behind Ohio State’s push for equality tries to empathize.

Smith has felt so much over his 57 years. The stares of the narrow-minded while out with his wife, Sheila, who is white. The pride of his middle daughter, Lindsay, having the comfort one day in college to say she was a lesbian. The regret of not doing more to help a closeted teammate as a football player at Notre Dame. The bite of racism growing up on Cleveland’s east side.

Smith and his friends used to walk to a sledding hill near the family’s home, but he was forbidden to go any farther. On the other side of Cedar Road was Little Italy — an ethnic conclave that historically had been cold toward blacks.

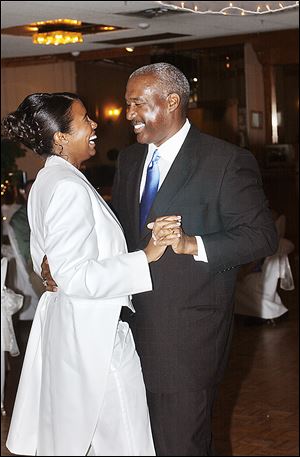

Ohio State University Athletic Director Gene Smith shares a dance with his daughter, Lindsay Smith, in 2007. Smith describes himself as an accepting person, whether it involves the sexual orientation of athletes at OSU or his daughter, who informed her parents while in college that she was a lesbian.

“My dad always said, ‘Never go across the street,’ and I never understood why at that age,” he said. “My dad was strong-willed, so you just did it. My mom eventually told me why. I began to understand things early.”

Today, Smith said, “I’m just a person of acceptance. Always have been.”

It is why Lindsay Smith, as a freshman basketball player at Dartmouth, asked her parents during one visit if they could stick around an extra day. She had something to tell them.

Out at dinner the next night, her mother, Sheila, ran through the scenarios.

Pregnant? School problems?

“Then I looked up at her, and said, ‘You’re gay?’” her father said to Lindsay, who later transferred to Arizona State and is now a police officer in Arizona. “She said, ‘How’d you know?’ That’s really how it happened. I kind of had an inkling. I wasn’t sure, so I just threw it out there. But she was relieved.

“For her to have the comfort level, the strength ... she knew it wouldn’t be an issue for me, because I’ve always tried to be positive about that type of behavior. Whether you’re at the dinner table or you see something on TV, how you talk in your living room, your home, there’s an impact.”

Smith wants to create a similar environment at OSU.

Last year, when a campus advocacy group expressed concern over the football staff making players who “loafed” wear lavender shirts as punishment, Smith spoke with Urban Meyer. The Buckeyes head football coach said the use of lavender — a color associated with homosexuality — was not meant to offend, and he promptly ordered the shirts changed.

“Please accept our sincere apologies,” Meyer wrote in a letter to Scarlet and Gay, an OSU alumni society. “We have core values of respect and honor within our program, and these are two principles that are central to my personal life, my coaching, and to Ohio State and its athletics programs. Bias has absolutely no role in how we think or operate.”

Fighting stereotypes

Smith’s foremost effort is simply changing the lexicon in locker rooms.

Society at large has never been more accepting, from the military’s repeal of the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy in 2011 to the fast-growing support of gay marriage. Yet on many teams, you would never know it.

Male team sports remain among the most closed sections of America in large part, advocates said, because of a gaping disconnect between perception and reality.

Old meathead stereotypes die hard, fueled by rare, headline-snagging bursts of intolerance — recall San Francisco 49ers cornerback Chris Culliver’s assertion at the most-recent Super Bowl that a gay teammate would have to “get up out of here” — but also the slurs players and coaches use mindlessly.

“I was as bad as they come,” said Patrick Burke, a co-founder of the You Can Play Project and a scout for the NHL’s Philadelphia Flyers. “I’d say, ‘You’re so gay,’ everything. Name a gay slur, and I’d say it. And I had nothing against gay people.”

Nor, he presumes, did his teammates who talked the same way.

“The words are stupid because they don’t reflect the true feelings of the people saying them,” Zeigler of Outsports.com said. “When someone uses a homophobic slur, they don’t mean, “I don’t like gay people.’ They mean, ‘I’m trying to express a level of frustration, and my coaches from peewee league used this word, and I’m going to use this word too.’ ”

Making things easier

Anderson, the OSU hurdler, distanced himself from friends on the football team after leaving the sport behind, saying he needed to escape the locker-room culture. At Ohio State, Smith wants no athlete struggling with their sexuality to feel unwelcome.

“Who knows what they’re going through psychologically, emotionally?” Smith said. “You have to make it easy on them to feel comfortable in our environment, because they are already dealing with something challenging if they haven’t come out.

“The worst thing we can have is for any athlete to put their head on the pillow at night and worry about that because of us, because of what we do. That’s just not right, so we’ve talked about it with our coaches. ... We don’t know what we don’t know.”

Could that atmosphere ever give way to the next step, say, a Buckeyes football or men’s basketball player coming out?

Smith is unsure. He understands why it would be difficult, why a football locker room filled with more than 100 players from different backgrounds — “some of them,” he said, “who grew up with a set of stereotypes” — would seem foreboding. As a defensive end at Notre Dame in the mid-1970s, he grappled with how to approach a teammate he believed was gay before ultimately deciding it was not his place.

“He never brought it to us,” Smith said. “That impacted me. I’m a relationship-type of guy. I just felt for him. I wish he had said something.”

Four decades later, there remains no well-worn blueprint. But Smith and others see attitudes shifting.

A new ballgame

Once someone you care for comes out, Burke said, “the ballgame changes.”

Burke, the NHL scout, co-founded the You Can Play Project last year in honor of his late brother, Brendan, who came out as openly gay in 2009 while a student manager for the Miami (Ohio) hockey team.

Before Brendan died in a car accident months after the announcement, he encountered near-universal support, including from his father, Brian, former general manager of the Toronto Maple Leafs and a red-blooded hockey lifer. Brian since has marched annually in the Toronto Pride Parade.

“You can teach an old dog new tricks,” Patrick Burke said. “My dad was in his mid-50s. He hunts, he fishes, he drives a truck, we own firearms. You pick a masculine stereotype and he does it. But the day after Brendan came out, and that was it, we’re gay-friendly now. What’s more important to you? Being able to use [slurs] or being there for your son or your brother?”

The truth

Anderson said he grew tired of living a double life.

Tired of covering his tracks. Tired of avoiding speaking to his parents. Tired of sleepless nights spent wondering how his family and team would respond when they learned of his secret. Tired of the same fears that already had nudged him away from football.

Last summer, after his freshman season, Anderson decided it was time. He came out first to his parents, then his friends back home in Arlington.

When Anderson returned to campus, he confided in a couple teammates. Mostly, he let others find out for themselves as he began living openly with his boyfriend, a fellow OSU student.

“We’d be together all the time,” Anderson said. “People started wondering and asking, and I was fine with the rumors. If you’re going to wonder, then at least you’re wondering the truth now.”

And truth was, the inquiring minds were fine with it. His parents were surprised but fully supportive. Teammates and coaches expressed encouragement. Beathea said he recruited Anderson because he thought he was a good kid with the talent to develop into an All-Big Ten hurdler, and nothing has changed.

Nothing, and yet everything. While recent knee surgery will leave Anderson a spectator for today’s final day of the Big Ten track and field championships in Columbus, he said he has never felt better.

“I should have done this earlier,” said Anderson, who even came out publicly at a university advocacy event last month. “It’s like a weight lifted. ... I was just happy. There were no more secrets. I don’t have to lie about anything else. I can say something and not have to be like, ‘Oh my gosh, I just said that, they’re going to know.’ You just feel so much better about yourself. I can just be myself.”

He praised Collins, who told Sports Illustrated, “If I had my way, someone else would have already done this. Nobody has, which is why I’m raising my hand.” Anderson feels the same way, wishing this wasn’t a story but glad to share it if it reminds other gay athletes they are far from alone.

Anderson is raising his hand.

Contact David Briggs at dbriggs@theblade.com, 419-724-6084 or on Twitter @DBriggsBlade.