Foster children were helped by medical trials

5/21/2005

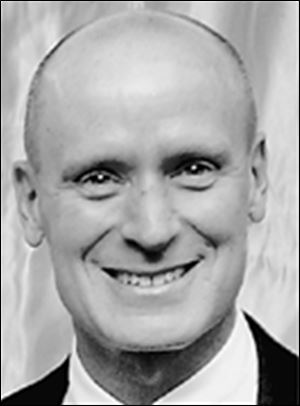

Mark W. Kline

SOMETIMES, hindsight is not 20-20.

In a recent editorial, The Blade criticized researchers who enrolled foster children with HIV in studies of anti-AIDS drugs without appointing an outside advocate for these children.

In particular, The Blade s editorial said: Exploitation by any other name is exploitation. The hard truth is these children were expendable because they were already sick, had no one to defend their interests, and were available.

Nothing could be further from the truth. We did not single out these children to be the only ones who received treatment. Instead, we included them along with all other children in the same situation in studies of potentially life-saving therapies. There is a great difference.

The decision should also be considered in the context of that era, when children with AIDS died quickly. They died young. I and others who treated them saw them die because available treatments offered only partial, short-lived benefits.

It was a devastating situation that we fought constantly.

Then, beginning in the mid-1990s, increasingly potent medications began to offer hope. After much study, these medications were approved for adults, but because there were no studies in children, they were not approved for children.

Those children whose parents could afford the drugs received them anyway from physicians willing to provide treatment off-label.

These doctors had to guess at dosages and which medicines offered the least harm to these children.

Clearly, studies were needed to figure out which drugs at which dosages worked best for these children. And time was of the essence.

As studies of these potentially life-saving remedies began in youngsters to define these important parameters, we who treated them had a choice. We could include children in foster care or we could exclude them from the studies.

If we had elected to treat only children in foster care, then perhaps the criticism would be just. That was not the case. Most of the children in clinical trials were not wards of the state, and they and their parents agreed to the treatment.

Would it have been fair to exclude foster children because they lacked parental advocates?

I personally think it would have been wrong and an ethical lapse to do so. They had to be offered the chance for treatment.

It was, at that time, their only hope.

As we learned from the studies, these are potent therapies that can extend the lives of children with HIV.

Should we have appointed advocates for these children? Our legal experts say it was not necessary because the treatments offered potential benefit to this very vulnerable population and they were being put at no more risk than other children in the same situation.

We did not single out foster children for research. We included them in it, if they and their foster parents wanted them to be part.

In this era when there are few youngsters in the United States born with HIV and when those who have the disease receive potent treatments, it is easy to forget the desperate times when nothing we did seemed to work, and children with HIV were dying quickly.

Those memories are fresher for those of us who work in the Third World where HIV is still a rapid death sentence for millions of children who cannot get these treatments.

Do I regret including these foster children in clinical trials?

No. I had to do something to help them, to extend their lives, which were as precious to me and others in my field as were the lives of those children who had parents to push us to provide them with the most potent treatments available.

Dr. Mark Kline is professor of pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine and director of the Baylor International Pediatric AIDS Initiative.