Science may explain gas prices, Dow, tax cuts

10/19/2004Economics may, indeed, be the "dismal science." But at least it's not just another art.

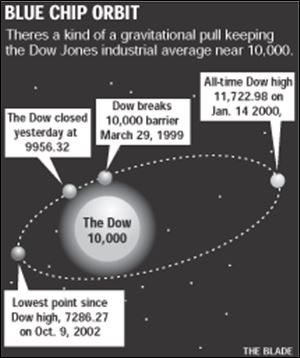

Today, we apply some scientific principles - borrowed from physics, astronomy, and chemistry - to answer these questions: (1) Why do cars seem to suck gas faster at $2 a gallon than they did when gas was $1 a gallon? (2) Why does the Dow Jones industrial average keep coming back time after time to the 10,000 level, even 67 months after the index first cracked the barrier? (3) Were President Bush's tax cuts inspired by Amadeo Avogadro, the Italian physicist who proposed Avogadro's law in 1811?

Let's start with fuel economy and Einstein's theory of relativity. No, of course, the revered scientist had nothing to do with crude oil. But he did establish that time is relative to speed.

Is it possible that gasoline usage is relative to price? Maybe not directly, but here's a theory: Many Americans are holding on to their old clunkers longer because they're afraid they might lose their jobs. Many others are cutting back on longer trips and, therefore, driving mostly around town - fewer interstate-highway miles translates into lower gas mileage.

So, perhaps it's not just an illusion. Your car might be eating gas at a faster rate than it once did.

Now, the Dow can't move very far beyond 10,000 because it is orbiting the 10,000 level - much as a planet orbits the sun - and it can't escape the powerful gravitation pull. While we normally view the market as a linear phenomenon, suitable for a line chart, perhaps it's really more suitable for a chart of the heavens. Since March, 1999, the Dow has criss-crossed the 10,000 barrier 23 times.

This has happened before. For example, the Dow first topped 100 in 1906, and it traded below 100 as late as 1942, a span of 36 years.

The Dow first went above 1,000 mid-day in 1966, but didn't close above 1,000 until 1972, nearly seven years later. And between late 1972 and late 1982, the Dow dropped below the 1,000 level 30 times. The Dow last traded under 1,000 on Dec. 16, 1982, making the total orbitaround the 1,000 level just short of 17 years.

Avogadro was one of the first thinkers to envision REALLY big numbers. His famous law, which wasn't validated until well after his death in 1856, concerned the number of atoms in a gram-molecule of gases. As chemistry students and trivia junkies know, the resulting "Avogadro number" is 6.0221367 times 10 to the 23rd power, or put another way, more than 602,000 sextillion.

Mr. Bush's tax cuts could total $1.9 trillion over a 10-year period. Admittedly, that's not quite as large as the Avogadro number. But it's still a very big number that could be expressed as $1.90 times 10 to the 12th power. That's 1.9 million million dollars. It's hard to visualize a number that huge, but we're going to try.

The U.S. Treasury Dept. says 454 $1 bills weigh a pound. So $1.9 trillion worth would weigh a little over 2 million tons, or as much as the Golden Gate, Mackinaw, and Brooklyn bridges combined, with the USS Enterprise aircraft carrier thrown in for good measure.

Treasury also says a mile-high stack of $1 bills would be worth about $14.5 million. At that rate, it would require a stack 131,000 miles high to take care of the entire $1.9 trillion - that's more than halfway to the moon.

Fortunately, the government doesn't much use singles to pay its bills. But perhaps we shouldn't spend all of our tax cuts in one place.

Getting back to the theory of relativity: Win the lottery, and you'll discover how many relatives you have.