PETE SEEGER, 1919-2014

Folk singer, activist dead at 94, played in Toledo

1/29/2014

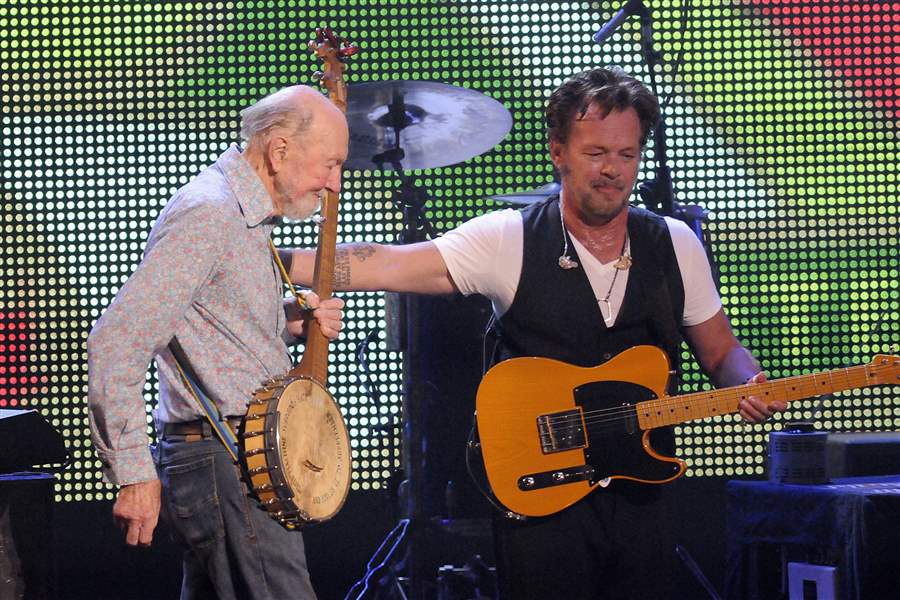

Pete Seeger is welcomed onstage by John Mellencamp during the Farm Aid 2013 concert at Saratoga Performing Arts Center in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. Seeger, an American troubadour, folk singer, and activist, died in New York on Monday at age 94. He had performed in Toledo at least three times.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

Pete Seeger is welcomed onstage by John Mellencamp during the Farm Aid 2013 concert at Saratoga Performing Arts Center in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. Seeger, an American troubadour, folk singer, and activist, died in New York on Monday at age 94. He had performed in Toledo at least three times.

ALBANY, N.Y. — Unable to carry his beloved banjo, Pete Seeger used a different but equally formidable instrument, his mere presence, to instruct yet another generation of young people how to effect change through song and determination two years ago.

A surging crowd, two canes, and seven decades as a history-sifting singer and rabble-rouser buoyed him as he led an Occupy Wall Street protest through Manhattan in 2011.

“Be wary of great leaders,” he said two days after the march. “Hope that there are many, many small leaders.”

The banjo-picking troubadour who sang for migrant workers, college students, and star-struck presidents in a career that introduced generations of Americans to their folk music heritage and brought him to Toledo at least three times, died Monday at age 94.

Seeger’s grandson, Kitama Cahill-Jackson, said his grandfather died peacefully in his sleep about 9:30 p.m. at New York-Presbyterian Hospital, where he had been for six days. Relatives were with him.

“He was chopping wood 10 days ago,” Cahill-Jackson said.

With his lanky frame, use-worn banjo, and full white beard, Seeger was an iconic figure in folk music who outlived his peers. He performed with the great minstrel Woody Guthrie in his younger days and wrote or co-wrote “If I Had a Hammer,” “Turn, Turn, Turn,” “Where Have All the Flowers Gone,” and “Kisses Sweeter Than Wine.” He lent his voice against Hitler and nuclear power. A cheerful warrior, he typically delivered his broadsides with an affable air and his fingers poised over the strings of his banjo.

Seeger played in Toledo in October of 1957 at the indoor theater at the Toledo Zoo. He also supported the Farm Labor Organizing Committee with shows at Whitmer High School in 1983 and 1992.

Baldemar Velasquez, president of Toledo’s FLOC organization, said Seeger was a great friend of the oppressed and he never failed to speak out against exploitation.

Henry A. Wallace,listens to Pete Seeger on a plane between Norfolk and Richmond, Va., in 1948.

“He was a giant fighter for justice,” Velasquez said.

The two men met in the mid 1970s and struck up a friendship when Seeger learned Velasquez was organizing farm workers and laying the groundwork for what turned into a multiyear boycott of the Campbell Soup Co.

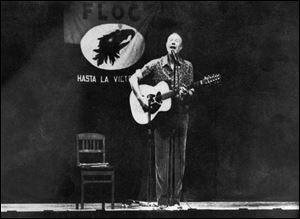

Seeger performed the benefit concert for FLOC at Whitmer High School in 1992 to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the organization.

“There was a big storm that closed the airport the night before and we thought we’d have to cancel or postpone the concert. He took a train all night from New York to be here and made it early in the morning on the train and the airports were still closed,” Velasquez said.

They performed two songs together during the concert, “Guantanamera” and “De Colores,” which Velasquez described as the anthem of farm workers.

“Pete had a bunch of women including my mom on stage holding a sign with the lyrics in Spanish and he taught the crowd how to sing the chorus in Spanish,” he said.

He last saw the folk icon about two years ago when Velasquez visited his Beacon, N.Y., cabin in the hills that overlook the Hudson River.

“He was very vibrant and alert and we talked about all kinds of politics,” Velasquez said.

In 2011, Seeger walked nearly 2 miles with hundreds of protesters swirling around him holding signs and guitars, later admitting the attention embarrassed him. But with a simple gesture — extending his friendship — he gave the protesters and even their opponents a moment of brotherhood the short-lived Occupy movement sorely needed.

Pete Seeger performed at Whitmer High School for a benefit for the Farm Labor Organizing Committee for more than two hours on a Sunday night in 1983. Attendance reports ranged from 800 to 1,100.

When a policeman approached, Tao Rodriguez-Seeger said at the time he feared his grandfather would be hassled.

“He reached out and shook my hand and said, ‘Thank you, thank you, this is beautiful,’” Rodriguez-Seeger said. “That really did it for me. The cops recognized what we were about. They wanted to help our march. They actually wanted to protect our march because they saw something beautiful. It’s very hard to be anti-something beautiful.”

That was a message Seeger spread his entire life.

With the Weavers, a quartet organized in 1948, Seeger helped set the stage for a national folk revival. The group — Seeger, Lee Hays, Ronnie Gilbert, and Fred Hellerman — churned out hit recordings of “Goodnight Irene,” “Tzena, Tzena,” and “On Top of Old Smokey.”

Seeger also was credited with popularizing “We Shall Overcome,” which he printed in his publication “People’s Song” in 1948. He later said his only contribution to the anthem of the civil rights movement was changing the second word from “will” to “shall,” which he said “opens up the mouth better.”

His musical career was always braided tightly with his political activism, in which he advocated for causes ranging from civil rights to the cleanup of his beloved Hudson River. Seeger said he left the Communist Party about 1950 and later renounced it. But the association dogged him for years.

He was kept off commercial television for more than a decade after tangling with the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1955. Repeatedly pressed by the committee to reveal whether he had sung for Communists, Seeger responded sharply: “I love my country very dearly, and I greatly resent this implication that some of the places that I have sung and some of the people that I have known, and some of my opinions, whether they are religious or philosophical, or I might be a vegetarian, make me any less of an American.”

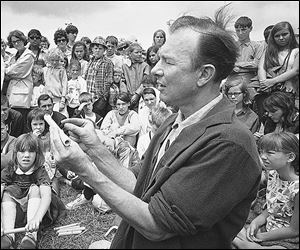

Pete Seeger conducted an instrument making session at the Newport Folk Festival, in Newport, R.I., in 1966. Seeger taught generations of Americans how to effect change through song.

He was charged with contempt of Congress, but the sentence was overturned on appeal.

Seeger called the 1950s, years when he was denied broadcast exposure, the high point of his career. He was on the road touring college campuses, spreading the music he, Guthrie, Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter, and others had created or preserved.