LOST YOUTH: TEENAGE SEX TRADE

Reports of runaways end up at bottom of investigation pile

Lack of manpower, parental interest deters probes

2/12/2006

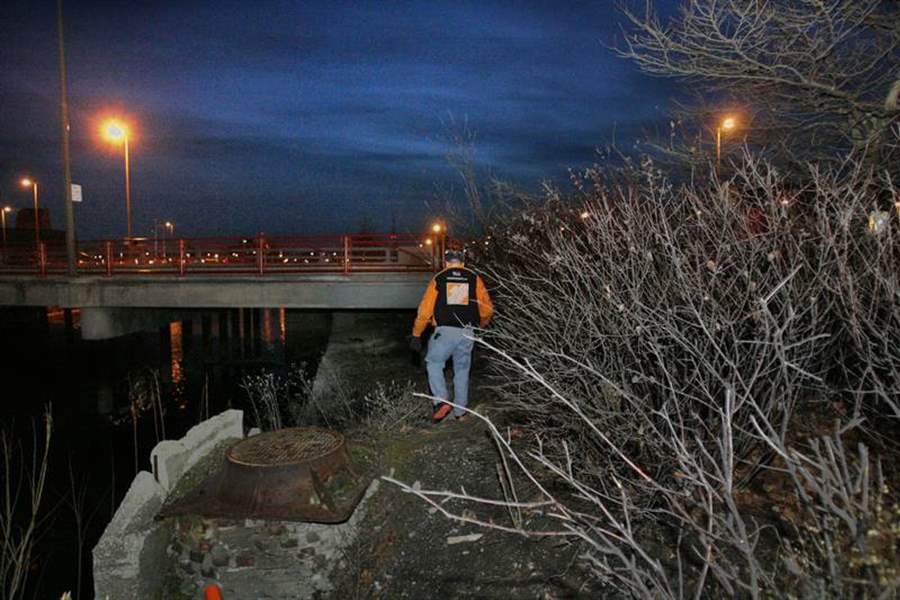

Bob Jones of Teen Street Outreach carries brown-bag lunches for runaways he may find near a Maumee River bridge.

Bob Jones of Teen Street Outreach carries brown-bag lunches for runaways he may fi nd near a Maumee River bridge.

It's hard to surprise a veteran police sergeant, but the hooker who was waiting to talk with Lou Vasquez did just that.

Glancing at her skirt and neat white blouse, Sergeant Vasquez was reminded of a uniform worn in a parochial school.

"Oh, my God, this girl -- I looked at her, and you could tell: Yeah, she's 14."

She was a runaway. Caught by police, she casually described sex acts she'd traded for money, sex videos she'd made with a 29-year-old man, and other teen girls doing the same.

That was in January, 2000. It was five more years before federal investigators, in unrelated cases, broke up an alleged ring that included 16 Toledo men and women charged with recruiting local young girls as prostitutes for truck stops and rest areas across the country.

Part of a nationwide crackdown on underage prostitution, the allegations were detailed last month in The Blade series "Lost Youth: Teenage Sex Trade."

But long before the indictments, Sergeant Vasquez, like most cops and social workers, knew that underage hookers tend to be AWOL from their families -- some of whom barely notice the teens' absence.

Sociologist Celia Williamson called these kids "the runaways, and the giveaways, and the throwaways."

"You find those [girls] in the gaps and the spaces in life that you can't really identify, because they're kind of lost around the fringes," said Ms. Williamson, a researcher at the University of Toledo who focuses on prostitutes.

"They get scooped out of those marginal spaces in life," Ms. Williamson added. "They don't even know what's about to hit them."

That's not to say all runaways are prostitutes. But, as pimps well know, lots of young hookers are runaways.

But for cops the monotony of runaway complaints -- especially the chronic offenders police call "frequent fliers" -- can become white noise compared with robberies, car crashes, and murders.

It's a mind-set suggested even by the allocation of manpower.

Twenty years ago, seven Toledo police detectives tracked missing persons full time. Today, only two detectives, Bob Noonan and Jim Anderson, have this task. With 2,199 such cases last year -- more than half of them minors -- the detectives spend more time on paperwork and phone calls than searching the streets, Detective Noonan said.

But some police agencies are changing this approach. Deborah Brady, a senior case manager with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, cited Milwaukee.

That police department, she said, created an aggressive protocol requiring investigation of each runaway case, including interviews at the homes of family, friends, and neighbors.

As a Milwaukee lieutenant told Ms. Brady: "We revised our whole strategy because we had this little case called the [Jeffrey] Dahmer case," a reference to the notorious serial killer and cannibal whose victims included teens.

Frantic parents

A father calls 911 for help (3:42 p.m.)

Aunt calls for help (4:16 p.m.)

Mother calls for help while running (5:04 p.m.)

Runaway reports that settle like sediment to the bottom of the pile sometimes can go unnoticed without consequence. But not so last May.

On a rainy afternoon, Toledo police took more than an hour and a half to respond to increasingly frantic 911 calls from two parents whose teenagers, federal prosecutors later charged, had been enslaved as prostitutes.

The parents -- a brother and a sister whose 14 and 15-year-old daughters were cousins and had been lured into a white Lincoln nearly two weeks earlier -- sat in a van outside the Toledo house where they believed the girls were imprisoned.

They called 911.

READ MORE: Captive teenage cousins suffer crash course in forced sex trade

Earlier that day, one of the cousins had been rescued by authorities from prostituting at a Michigan truck stop. After Washtenaw County deputies released her, she led her mother and uncle to a brick house with barred windows in southwest Toledo.

The father made his first call at 3:42 p.m. In the more than 90 minutes before police arrived, 911 logged three more calls from the family, plus numerous appeals from horrified neighbors.

But cops were busy with a shooting call and rainy-day fender benders. Frustrated and fearful for his daughter, the father grabbed a tire iron and stormed the Downing Avenue house.

Cops arrived at a savage and bloody free-for-all in the front yard -- just what a Washtenaw County, Michigan, detective had feared earlier.

In Ann Arbor, near where deputies found the 15-year-old at a truck stop, Detective Greg Raisanen sat stunned by the girl's story. At 8 that morning, Detective Raisanen said, he was in contact with Jim Anderson, laying out the case for the Toledo detective: underage girls, held against their will, turned into sex-trade slaves. The teen found in Michigan, he said, didn't know the address of the Downing Avenue house, but "she could find it if taken to the area."

"Look," Detective Raisanen remembered telling his Toledo counterpart, "this is not just a runaway." He said he also warned Detective Anderson that the missing girl's father seemed upset enough to act on his own.

The two police officials spoke by phone at least four times during that day, the Michigan detective said.

Reviewing his report, Detective Anderson said: "Yes, I put down [that the missing girl] was possibly back here in Toledo with a one Deric 'Mackavelli' on Downing. I wrote down the information about his car and the information about the house."

Trouble was, the man's last name was an alias. Plus, Detective Anderson said, he was given a specific house number on Downing Avenue -- a two-block street of some 20 houses -- that didn't exist.

In his view, he said, the misinformation was enough to prevent further investigation. He conceded that phone calls from another police agency about the location of a captive minor on a specific street, even without an address, was normally a tip he'd pursue.

But he added: "You have to understand, there are only two [missing-persons] detectives. ... Possibly that day I may have had something else I had to do. I don't recall. ... Normally, or generally, if somebody gives me some particular hot information, I would go right out on it, but I didn't this time."

Bonita Brazzel Thomas of Teen Street Outreach seeks runaways at the Anthony Wayne Bridge.

'Get out'

Rescued from the house, the girl and her cousin had something too many runaways lack -- determined parents.

Just last week, 17-year-old and 18-year-old girls showed up at Connecting Point, a Cherry Street haven for troubled kids. Outreach director Tammy Battle described both as "push-outs."

"The one parent said, 'You're 18. Get out,' " said Ms. Battle, who'd called the girl's mother.

"The kid said she's never had anyone who cared, who really motivated her. She said, 'If I didn't go to school, nobody cared. And I went to school anyway, and I got good grades, but nobody cared about that either.' "

Also last week, outreach workers found two 11-year-old runaway Toledo girls. One had a pocketful of cash from "a man she called her uncle," Ms. Battle said.

But she felt it was too early to pry; while few runaways admit to transactional sex, they trigger plenty of suspicion.

Laura Linthicum, family services coordinator for Lucas County Children Services, sees foster home runaways return with brand-new clothes.

"Who's been clothing them?" she asked. "Who's been feeding them?"

Differing viewpoints

But tackling a problem is complex when people can't even agree on what they see. Take the dazed 13-year-old girl in a Toledo hospital on March 9, 2004.

The parents who'd patrolled the streets searching for their missing daughter saw a gullible child who'd been drugged and forced into sex with at least a dozen men, sometimes traded for crack by her captors.

But in the eyes of police, she was a small-town teen who'd willingly left a loving home three days earlier for a friend's house in Toledo, where she said she had consensual sex.

Where the parents saw a bruised rape victim whose recently diagnosed mental disorder they had only begun to understand, police saw a chronic runaway.

"To some extent, if they're under age [runaways having sex], they're all being exploited," said Sgt. Greg Smith, who helped locate the 13-year-old two years ago and last year was among the first to arrive at the Downing Avenue scene.

"If a 15-year-old girl seems to want it," he added, "is she being exploited? In some way it is being exploited, but it's different than a girl who is scared and being beaten into it."

In the Downing Avenue case -- which resulted in the federal indictments of three people -- Detective Anderson said that even without investigation he had "a gut feeling" that the situation "wasn't as urgent as it appeared to be."

Measuring the problem

So how many runaways willingly trade sex for money, drugs, or even food and shelter?

Everybody guesses. Nobody knows.

In an informal survey two years ago, Lucas County juvenile probation officers estimated that some 50 youths among their caseloads were likely prostituting themselves, said Mike Brennan, assistant Juvenile Court administrator.

Yet, that same year, girls and boys were charged with soliciting just nine times.

Many cops see young prostitutes as victims, not criminals, and bring them in on disorderly conduct or runaway charges. But with no arrest records or other documentation, the extent of teenage sexual exploitation is one big question mark, Mr. Brennan said.

John Rabun, vice president of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, has fought teenage commercial sexual exploitation for 20 years.

He knows that runaways' street-wise veneers make them seem older than their years.

"These kids, who can do 'X' number of tricks in a day and talk glibly about it, and cuss you out in 15 languages, and come across as incredibly hard -- you forget they're kids."