Felonious juveniles in Lucas County often avoid serious jail time

9/23/2007

From 2002 to 2006, Lucas County Juvenile Court sent 315 youths to an Ohio Department of Youth Services prison.

First of three parts

On the fourth floor of the Lucas County jail, a prisoner who is not even old enough for a driver s license sits in limbo.

Innocent until proven guilty, the 15-year-old is too young to be jailed with adult men. But juvenile court has already washed its hands of him. So until his trial Oct. 29, Robert Jobe eats alone, exercises alone, and sits alone in a putty-colored juvenile holding cell with a television.

The charges against him, and his rap sheet, probably won t get him a lot of sympathy.

Before the North Toledo teen was arrested in February in the shooting death of Toledo police Detective Keith Dressel, he d been picked up by police at least four times in the previous eight months including the month before, when officers found him in a carry-out, a loaded handgun nearby.

Police last summer spotted him leaving a drug house, and on another occasion, they d come across the 145-pound kid in an otherwise empty house. At that time, they said, the teen was high. He had a joint tucked inside his ball cap, and police found a crack pipe.

At some point, authorities strapped an electronic monitor around his ankle. He cut it off and ran.

Before a juvenile judge ordered him to stand trial in the adult system, Robert Jobe was just one of the 10,000-plus delinquency cases each year that passes through Lucas County Juvenile Court.

Unlike the adult system, juvenile justice is a tightrope stretched taut between the goals of rehabilitation and punishment. And nowhere did those sometimes conflicting aims crash head-on as they did in the case of Robert Jobe.

After the teen allegedly shot and killed the vice detective on a foggy winter night, Toledoans across the city had questions.

How could a kid with so many prior arrests still be out on the street? And how many other Robert Jobes are out there?

A look at case files inside Lucas County Juvenile Court offers answers.

And they re startling.

The Blade this summer reviewed thousands of court files and police reports on every juvenile arrested on felony charges from 2002 to 2006. Police, parents, court officials, youth advocates, counselors, and youths were interviewed.

Felony cases

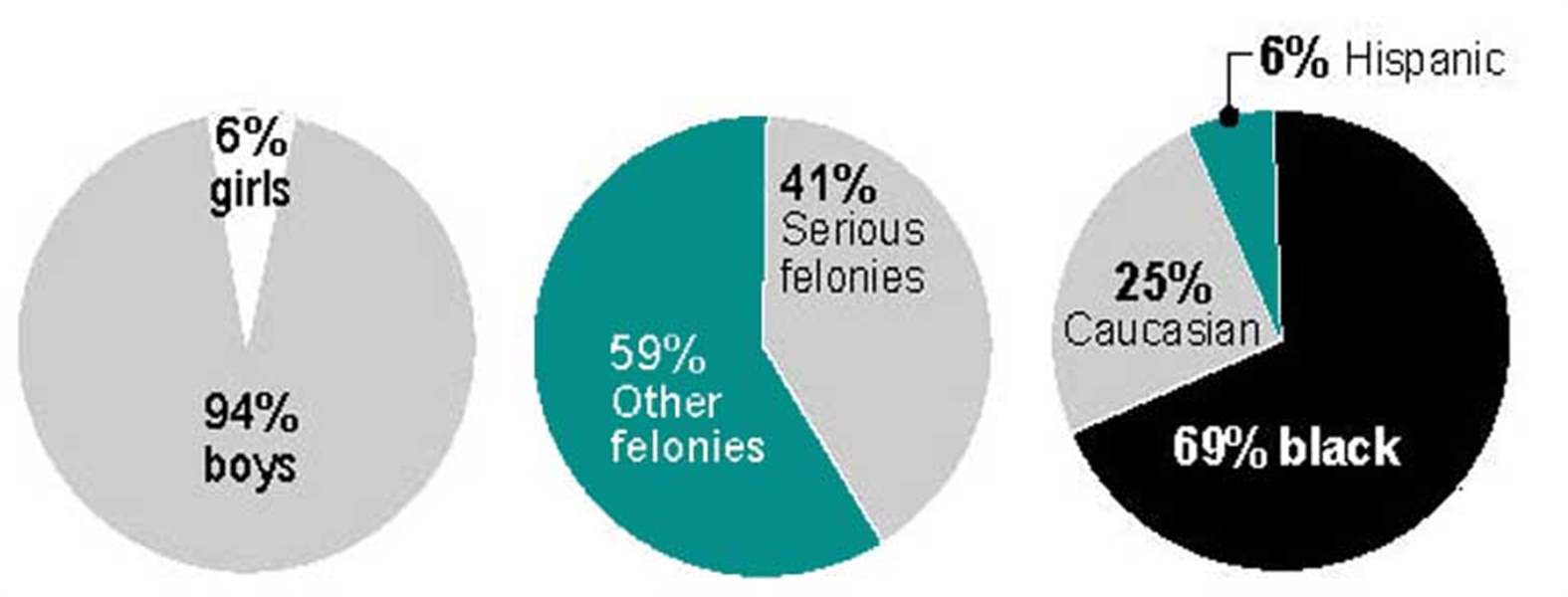

In the five-year period reviewed by The Blade, 3,966 youth some as young as 7 were charged with 8,006 felonies and subsequently found delinquent (juvenile court parlance for guilty ) of those charges or versions of them.

Robert Jobe, 15, is charged with the murder of a Toledo detective. Juvenile court has washed its hands of him.

Those are 3,966 youths with arguably worse criminal records than the 15-year-old accused cop killer known on the streets as Bobby White, whose record until earlier this year was made up only of misdemeanors.

Moreover, the Blade analysis found that at least 1,084 of those youths between 2002 and 2006 were found delinquent of first or second-degree felonies.

These were youngsters who robbed victims with handguns, who set fires to homes, who assaulted, raped, and murdered.

By the time they were facing serious time, many juvenile criminals had racked up records that included a string of dismissed charges, cases that were diverted to other programs, and convictions that drew no substantial prison time.

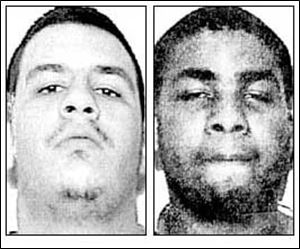

A few were juveniles such as Charles Rodriguez. His rap sheet began by age 11. A week after he turned 17, he fired a gun into a crowd and wounded four people. This year, at 21, he shot and killed a man in a jealous rage.

And then there was Antonio Rogers. Seventeen when he was put on probation for breaking his girlfriend s jaw in 2004, in 2005, he shot and killed her. Afterward, he took his own life.

Richard Schmidbauer, head of Wood County s juvenile detention center, is adopting some of Lucas County s policies.

But allowing heinous and relatively rare crimes to define this court is unfair, say those who work inside the Lucas County Juvenile Justice Center.

Evaluating cases

The juvenile justice system confronts defendants whose ages and cognitive abilities sometimes don t pass into double digits. It s a system sometimes frustrated by absentee or abusive parents, a system hobbled by gaps in local mental health and substance abuse services.

And, in Lucas County, it s a system that sends minors to adult prisons only as a last resort.

It s not so easy, sifting true criminals from youths who commit once-in-a-lifetime, adolescent mistakes.

I talk to the kids, I talk to everyone in the courtroom, Lucas County Juvenile Court Judge Denise Cubbon said. I try to figure out, Did this kid do something stupid, or is this a budding sociopath? More often than not, it s somewhere in between.

My breaking point

The mother wants her son behind bars.

David Valerio with his mother, Deborah Cox, were ordered to take glass-blowing classes, an art therapy course offered through Lucas County Juvenile Treatment Court. Michael and David have been drug-free for months.

His first arrest, at age 5, occurred after a neighbor accused him of spray-painting her cars. Now 14, he breaks curfew and gets drunk. He s accused of threatening neighbors, stealing bikes and beer, and breaking into homes.

In court recently, his attorney assured him: Admit to stealing a bike and his mom s beer, and prosecutors would reduce a felony to a misdemeanor. He d be home by afternoon.

His mother threw up her arms: I just don t think these kids learn a lesson.

Doug Allen agrees. A veteran Toledo gang task force detective, he said he s long watched gangs pluck new members who are barely out of kindergarten, targeting youngsters from dilapidated neighborhoods as well as homes with hefty incomes. To him, juvenile crime is like any other most often fueled by greed and power.

Kids are making a conscious decision to rebel, Detective Allen said. Spurred by violent media, we teach them that shooting and rebellion is a glorified and strong and powerful thing.

The answer: Get thugs off the streets. To him, it s as simple as that.

Even some teens agreed that time behind bars means time to think. David Valerio, now 17, said it was his choice to smoke marijuana even though he knew better.

Inside a sparse cell at the downtown Juvenile Detention Center last year, atop a thin mattress on a cement bunk, everything just started running through my head.

The dope. Running and stealing. Flopping at friends houses and sleeping in a van.

I broke down and started crying. I didn t want to do it anymore. I was tired of it. The lifestyle wasn t helping me none. It wasn t helping my family none.

Now drug-free, he said, detention was my breaking point.

Changing direction

But short-term lockup and long-term prison stays are two different things.

Scattered throughout Ohio are eight state Department of Youth Services prisons that, in theory, house the most dangerous of the state s young offenders. They can be held there, with rare exception, until they re 21.

But what about youths who are simply detained until the next court hearing? Or those whose sentences won t last more than a few weeks?

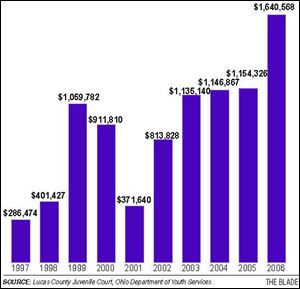

From 2002 to 2006, Lucas County Juvenile Court sent 315 youths to an Ohio Department of Youth Services prison.

Six years ago, the Juvenile Justice Center opened on Spiel busch Avenue, replacing the 1950s-era, roach-ridden Child Study Institute around the corner on Michigan Street. The $24 million facility marked a tectonic shift in the way Lucas County and Ohio treats troubled youths.

Along with security cameras and computerized locks, the new center features community areas, meeting rooms, and in detention classrooms and common space. The goal is to teach youths how to maneuver around common adolescent potholes: impulsiveness, peer pressure, and undue risk-taking.

Stints average 10 to 12 days, officials said. Not much time to alter behavior, but research suggests overly aggressive punishment can backfire.

Kids are dominated by their emotion [and] spontaneity, said Richard Schmidbauer, head of Wood County s juvenile detention center, which is now adopting some Lucas County policies. When you kill a fly with a sledgehammer, kids act out even more, he said.

Scared straight?

To be sure, plenty of great youngsters are out there.

And some of them will do stupid or even violent things before they grow into law-abiding adults. Serious felony court cases reviewed by The Blade represent just 3.5 percent of the overall delinquency caseload during those five years.

Many juveniles who would have gone to youth prison were diverted to a variety of programs. Over the past 10 years, the state has channeled funding from its youth prison systems back to communities for these programs.

This strongly suggests that relying chiefly on prison for punishment is flawed logic and could turn juvenile criminals into adult criminals, according to retired Judge James Ray. With 30-plus years on the bench, the recent past president of the National Association of Juvenile and Family Court Judges retired in March.

He s familiar with a common question: Why not just lock up bad kids and teach them a lesson?

But presiding over juvenile court for nearly two decades brought the judge to a different point of view. The responsible way to raise a child, he believes, is making him think, making him understand his environment, and how he fits into that environment, a goal that includes a variety of methods.

Why should the juvenile court lock up a child at 13 who has stolen a car and never let them out? asked Judge Ray. What have you got? You have a nation full of prisoners that are costing you, the taxpayer, $60,000 a year per child.

He s not alone in his thinking.

There s a tendency to want to get tough when getting tough doesn t seem to work, said Edward Latessa, chairman of the University of Cincinnati s criminal justice division.

He and others, including a panel in 2004 convened by the National Institutes of Health, conclude that recidivism rates suggest boot camps and other scared straight programs don t deliver what they promise.

A week after he turned 17, Charles Rodriguez, left, fired a gun into a crowd, wounding four people. This year, at 21, he shot and killed a man. Antonio Rogers, right, was put on probation at 17 for beating up his girlfriend. A year later, he shot and killed her. He then killed himself.

Rather, he said, courts should look at a person s criminogenic factors things like personality and attitude, peer groups and family relationships, substance abuse, or lack of education.

Much like a doctor using weight, age, and family history to help assess patients, Mr. Latessa said, juvenile justice authorities should weigh criminogenic factors to gauge youths risk of committing crimes and for predicting which programs might help.

In Lucas County, more than 40 such programs exist. Mentoring can help juveniles who need strong role models. Intensive counseling might best suit young sex offenders. For those nearing adulthood, community service could teach everything from carpentry to boat-building to landscaping.

Many such programs came about after a 1993 policy change, when the state made it clear to local officials that they would accept fewer young prisoners.

Decreases in crime

State law now diverts funds away from overloaded youth prisons back to the counties, where local courts set up programs for their lower-risk youths. The University of Cincinnati s Mr. Latessa said the new approach slows juvenile courts revolving doors.

Two years ago, he classified nearly 15,000 delinquents on a four-level scale, from low to very high-risk offenders, and sat back to watch their recidivism rates. Low and moderate-risk juveniles who were imprisoned for long periods of time returned to court up to six times more often than the same risk-level youths who d been diverted to some community-based programs.

For one thing, lumping offenders together behind bars exposes lower-risk criminals to their hardened counterparts, Mr. Latessa said.

In other words, a first-time car thief behind bars might learn not only how to steal cars more effectively but also how to deal dope or break into homes.

I want people coming out of facilities better than when they went in, not worse It s easy to say, Lock them up. But A, we don t have the money, and B, it s not good policy.

Still, it s tough to say exactly why crime overall is down.

Over the 10 years in which so many young offenders were rerouted to community programs rather than prison, the number of minors committing felonies statewide has decreased by about half, according to the Ohio Department of Youth Services.

But is that just a slice of the national trend?

According to the U.S. Department of Justice s report on juvenile crime last year, overall juvenile crime fell to a 20-year low by 2003, pulled down in part by sharp declines in murder, rape, robbery, and property crimes.

Signs of success

So how do you predict who will succeed? Who fits into what program? And, most important for the public, who s dangerous?

On any given day at the Lucas County Juvenile Justice Center, those questions are being asked at a meeting going on somewhere at a probation officer s desk, a conference table, or with a detention officer or psychologist.

On one particular day, the discussion centered on a 14-year-old. His mother is a heroin addict. The man he knew as his father is dead.

He fights. He gets stoned. Police reports say he s thrown rocks at houses, filched tortilla chips from a local store, and stolen garage siding. They say they ve caught him with marijuana more than once.

But juvenile court officials biggest worries this day are his domestic violence charges. Among his latest victims: his great-grandparents, who are raising him.

He throws things and breaks furniture. He orders his great-grandmother to drive him places. If she doesn t, he takes her keys. When his 84-year-old great-grandfather refused to give him money, police say the teen punched him in the face.

In a tidy conference room on this day, his great-grandmother sat quietly with her hands neatly folded in her lap. His aunt wept. The court-appointed mentors, counselors, and probation officer were gentle but honest.

It s a no-brainer. He can t go home.

We re waiting for a tragedy to happen.

He s a feral kid.

There s no current charge against him, but the boy hasn t gone to school a probation violation so he will be arrested.

Such meetings never make headlines, said Deb Hodges, head of the court s probation department. But every day, they mark the incrementally steady successes of the court.

The teenager will get substance abuse and family counseling, she said, and will probably spend time in detention. He might be removed from the home.

With luck, he might become a success story like, for example, David Valerio and his younger brother, Michael.

They say they ve been drug-free for months. Having been through court-ordered glass-blowing classes with their mother one of several art therapy classes offered through Lucas County Juvenile Treatment Court the results of their work are watery and elegant swirls of light and color that were recently exhibited at the Toledo Museum of Art.

They now plan to set up a glass-blowing business together. David, 17, who told The Blade he d used his time in lock-up to rethink his life, is the quiet worker. Michael, 14, is the salesman.

He hustles, David said recently, ribbing his brother.

But most people will never hear about the juvenile court youths whose futures look promising.

Most times, said Ms. Hodges, you only hear of the horror stories.

Who goes, who stays?

As they do every Tuesday, one lunch hour earlier this summer, court and detention staff, attorneys, and counselors, reviewed the list of all 66 juveniles in detention that day. The questions don t change: Who gets released? Who stays?

One youth pulled a gun. Another is a burglar. And this one, she s accused of peddling dope with her mother. Also on the list that day were a handful of sex offenders, suspected prostitutes, and several youths waiting for court dates on domestic violence charges. There was a girl whose parents won t come to the jail to get her. There was a sometimes violent 17-year-old boy whose brain development is no more than a kindergartner.

It s too early, court officials said, to say exactly why detention center numbers have recently climbed into the 80s and 90s, after holding steady for years in the 60s and 70s.

But this Tuesday meeting underscores one certainty: Robert Jobe was never the subject of any such discussions, not until the slaying of Detective Keith Dressel.

Even with a concealed-gun misdemeanor, his record was sparse unlike many of those reviewed by The Blade and inside detention, he was a model prisoner.

He followed orders and was notably polite. Most significantly, his rap sheet included no felonies, and, despite struggling with police during one arrest, his record didn t otherwise include violence.

Robert Jobe? said Dan Pompa, juvenile court administrator, after the meeting. That kid would never have been on our radar.