Citizens seek a say without 'pay to play'

11/3/2005

When Steve Musgrave worked the radar in Vietnam, his destroyer escorted civilian boats through the Gulf of Tonkin. Officers warned the smaller craft to paddle slowly to avoid triggering deadly mines.

Mr. Musgrave, his body now worn by illness, has found navigating Congress a more difficult mission. He says he ran into a blockade trying to change a federal pension rule that has capsized his family below the poverty line.

Congressmen brushed him off. Ohio's U.S. senators didn't return his calls, and they ignored letters a state representative sent on his behalf.

Mr. Musgrave, 52, has never donated to a political candidate. He lives in Canton, miles away from two of President Bush's biggest fund-raisers, W.R. "Tim" Timken, Jr., and Walden O'Dell, whose companies have received nearly $300 million in federal government contracts and trade subsidies since 2001.

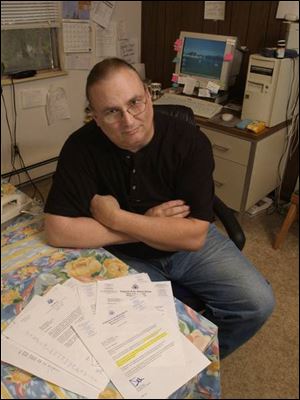

When he wrote to U.S. Rep. Ralph Regula (R., Canton) and other lawmakers, Steve Musgrave received little help in his quest to change a law that limits his veteran s disability benefits.

"I wish I was one of those guys," Mr. Musgrave said recently.

The contrast highlights a question some political activists and analysts have raised for decades, even centuries: How can Americans influence public policy without giving big campaign cash?

Some advocates say changes to campaign and election laws - including proposals on Ohio's Tuesday ballot - could give the little guy more of a chance to be heard. Some point to what they call a "pay to play" system in which only big campaign contributors are heeded.

Others call previous election "reforms" ineffective and the ballot measures unwise. Some say contributions and political clout aren't connected and that such reforms are just ploys to give Democrats more power.

Still others say Mr. Musgrave and people like him should peg their hopes to the Internet.

"It's the money chase that is the problem, and it really is something that is harming our entire democracy," said Bob Hall, research director for nonprofit Democracy North Carolina, which operates in a state that is experimenting with publicly financed elections. "It hurts the voters. It hurts the candidates, and it really hurts the small donors who used to think they were doing something."

Big donors or fund-raisers get no special access or influence with politicians, said Bob Bennett, chairman of Ohio's Republican Party and one of President Bush's top fund-raisers in 2004.

"Thousands of people get to meet the President," Mr. Bennett said. In Ohio, he added "almost anybody that wanted to see the President last year had the opportunity to do that."

Though seemingly a modern conversation, the intermingling of money and politics is as old as the Republic. The mid and late-1800s were marked by allegations of businessmen buying votes in Washington, leading to the first wide-scale campaign finance reform in 1907.

Congress tightened fund-raising rules again in the 1970s, after Watergate, and again in 2002, when the McCain-Feingold act restricted campaign spending by political parties and some outside groups, slowing the flow of "soft money."

Meanwhile, campaigns have increasingly craved cash.

Spending by presidential candidates nearly quadrupled from 1984 to 2004, after adjusting for inflation, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. It nearly doubled from 2000 to 2004.

The average cost of winning a U.S. House or Senate seat increased by more than 50 percent, in inflation-adjusted dollars, from 1986 to 2000, according to the nonpartisan Campaign Finance Institute.

Critics say the rising price of elections - including television advertising, computer-based voter targeting systems, and campaign staff salaries - gives large donors and skilled fund-raisers political leverage.

Mr. Timken, for example, has donated $3.81 million to state and federal candidates. He has traded jovial letters with Ohio Gov. Bob Taft. President Bush recently named him ambassador to Germany. In the past four years, the federal government has given his ball-bearing company $259 million - money that came from tariffs levied on its foreign competitors.

Compare that to Mr. Musgrave, who says depression, anxiety, migraine headaches, and spinal problems - which doctors call unrelated to his Vietnam tour - keep him from working. He and his wife survive on a $1,109 monthly disability check from the federal government, which he says doesn't nearly cover their medical bills.

His wife wants to work. But federal law says anything she earns would count against his pension.

Mr. Musgrave set out last winter to change those rules. He wrote his congressman, Republican Ralph Regula, who replied that he understood Mr. Musgrave's frustration - but didn't suggest a course of action. In a second letter last month, Mr. Regula suggested Mr. Musgrave call one of Ohio's U.S.senators.

Mr. Musgrave had already called and written both Sens. Mike DeWine and George Voinovich. They never replied, he says, even after a state representative wrote them a follow-up note. He finally got a response from U.S. Rep. Marcy Kaptur's office in Toledo, which requested a government estimate on how much changing the law would cost.

"I wasn't that great of a soldier," Mr. Musgrave said. "I didn't get any medals of honor." But he and the other veterans affected by the pension rules are "not getting responded to, we're getting stepped on ... I think we deserve better than this."

If you believe American democracy is tipped against people like Mr. Musgrave, who can't mobilize big donors, write large checks, or don't belong to wealthy interest groups, such as labor unions, experts cannot offer a united prescription. They disagree on the best way to change the system.

Their ideas span the political spectrum, including Ohio's Issue 4, which would change how the state draws legislative and congressional boundaries. The new lines would emphasize competition and likely force several of the state's congressmen into challenging races by 2008; last year, the state's closest U.S. House campaign was decided by 18 percentage points.

Proponents say the measure would force congressmen to be more accountable to constituents and less to big donors, because every vote in the district would count. Opponents say it could have the opposite effect: Politicians would need more money, more often, to survive constant challenges.

Backers of a companion measure, Ohio's Issue 3, hope to empower smaller donors by limiting campaign contributions.

Those opposed, including top GOP state officials, say the changes are ruses to give ready-made liberal groups with vast memberships, such as unions, too much influence over state politics.

If Issue 3 passes, political contributions for each election, per person and across the board, would be capped at up to $2,000 per candidate, depending on the race, and no more than $25,000 total per year. Ohio contributors now can give up to $10,000 per candidate, per election.

The most controversial portion of the amendment has become the creation of a new donor class called the "small donor political action committee."

The new PAC could solicit only a maximum of $50 per individual. But its contribution limit would increase considerably, compared to limits for traditional PACs. The small donor PAC would have a $20,000 per election limit for statewide candidates, compared to $1,000 for traditional PACS, which can take in more than $50 per person.

Keary McCarthy, spokesman for Reform Ohio Now, said the new PAC rules would encourage more people to participate in politics.

"Inherently, contribution laws should be democratic," he said. "The reason we've been in so much trouble in Columbus with so many scandals is because a small number of special interests have heavily contributed to candidates and those politicians only serve the interests of those who gave the money."

Ohio Attorney General Jim Petro, state Auditor Betty Montgomery, and Secretary of State Ken Blackwell wrote a letter that opposes Issue 3, Issue 4, and two others, urging voters to oppose them or risk losing GOP control of the White House.

"Ohio played a deciding role in re-electing President Bush in 2004, and the same liberal activist groups that spent millions of dollars trying to defeat the Republican agenda last year are back again with another attack," the letter said. "This time, they have devised a stealth campaign to dismantle the integrity of Ohio's election system. Their ultimate goal is to set the stage for a Democratic takeover from Ohio to the White House by 2008."

Lower caps have failed to drain money from federal politics: The 2004 presidential election, when donors were limited to $2,000 each, was the most expensive in American history.

Publicly financed elections at the state-level - once considered pie in the sky reform - have started to take root, though proponents say there's still little appetite to spread them nationwide.

Maine and Arizona finance candidates who gather a qualifying number of $5 donations.

Maine's system provides legislative candidates an initial stake and then matches that money up to two times, but only if a challenger using private money ramps up the spending, said Jonathan Wayne, executive director Maine's Commission of Governmental and Elections Practices.

"I think the program has succeeded in attracting new candidates," he said. "Many candidates also report they feel less beholden to lobbyists because the lobbyist are not arraigning for campaign contributions and there is less private money being paid directly to candidates." Two-thirds of the money to finance the Arizona system comes from "surcharges" on civil and criminal fees.

"The general consensus is that clean elections help level the playing field and allow citizens to run who otherwise wouldn't consider it," said Brian Wendel, spokesman for Arizona's Citizens Clean Election Campaign. "Now they can actually stage a viable campaign."

Presidential politics already include a publicly funded component, which President Bush and Sen. John Kerry opted to disregard in the 2004 primaries, so they could raise more money privately.

Taxpayer financed elections seem un-American and a bad idea to some, including Patrick Basham, a senior fellow at the free-market oriented Cato Institute in Washington.

He and others believe that transparency in giving is the best way to hold back undue special interest. The logic is that if you know whose giving the money, then as a voter you can understand the potential motivations of the politician. The political system should be about having the information and not restricting expression, he said.

"If you don't let anyone have influence, don't let anyone have access in a disproportionate sense, then you're living in a sort of never-never land. And the instruments you construct and implement to create that idealistic system are going to cause all kinds of other problems," Mr. Basham said.

In a paper released in June, Mr. Basham argued that campaign finance regulations have backfired, leading to less competitive races at the state and federal level and have only enhanced the prospects of the incumbents.

He favors ending donor limits, coupled with full disclosure.

Let the CEO of a company give $1 million - but make sure everyone knows it, he said.

Candidates would find themselves restricting donations themselves, he said. And challengers who don't have the advantage of incumbency, such as free government mailings, would have a chance, he said.

It used to be to raise political money, you needed a place to hold the fund-raiser. Now you might only need a Web site.

Tech-savvy political consultants say the Internet is rapidly providing "little guys" with ways to bundle small donations around an ideological cause - such as opposing the Iraq war or supporting the President's Supreme Court nominee - and could eventually reduce the cost of campaigns.

Former Vermont Gov. Howard Dean was the front-runner early in the 2004 campaign for the Democratic nomination for president, largely because of his Internet fund-raising prowess.

After he dropped out of the race, Mr. Kerry picked up the mantle and raised $100 million of his roughly $250 million in cyberspace, his handlers have said.

"None of those [donors] were looking to peddle influence," said Democratic strategist Jim Ruvolo, who helped run Mr. Kerry's Ohio campaign. "The Internet gives you an opportunity to join with others - the whole blogging thing, the ideological Web site. It allows people to join with others without going to some union hall where you feel uncomfortable."

E-mail and cheap Web advertising could reduce the money campaigns need for television, strategists say - along with the influence of big money. Until then, one champion fund-raiser has some time-honored advice for people hoping to change the world without opening their checkbooks: volunteer on a campaign.

"If you've got an interest, you've just got to reach out," said Doug Corn, a Cincinnati insurance salesman who raised $250,000 for President Bush last year. "The door's open - you've just got to go through it."

Staff writer Christopher D. Kirkpatrick contributed to this report.

Contact Jim Tankersley at:

jtankersley@theblade.com

or 419-724-6134.