Calls for convention to change Constitution mount

12/11/2011

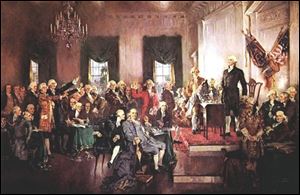

A painting by Howard Chandler Christy depicts the scene of the signing of the U.S. Constitution on Sept. 17, 1787, including George Washington, at right, and, seated in foreground from left, Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin, and James Madison. Article V allowed for further constitutional conventions, a step never taken.

PITTSBURGH -- The American Constitution is studied throughout the world as a model blueprint for governing a free people, its framers revered for achieving what Catherine Drinker Bowen famously labeled the "Miracle at Philadelphia."

But concerns over a seemingly dysfunctional climate in Washington and issues ranging from the national debt to the overwhelming influence of money in politics have spawned calls for fundamental change in the document that guides the nation's government. From the left and the right, a small but seemingly growing cadre of scholars and activists is calling for a new constitutional convention to respond to the changes and excesses of current politics.

Such a convention is envisioned in the text of the founding 1787 document but has never been employed.

The amendments that, among other things, ended slavery, enfranchised women, and established, then ended, Prohibition were adopted through two-thirds votes in Congress, ratified by three-quarters of the states. Article V of the Constitution, however, in the same section that set up that procedure, set forth the legal possibility for the legislatures of two-thirds of the states to instruct Congress to call a constitutional convention, a mechanism, in the view of some government critics, whose time has come.

"We need some constitutional amendments rather urgently that could not be enacted any other way," said Richard Labunski, a University of Kentucky scholar and the author of The Second Constitutional Convention: How the American People Can Take Back Their Government.

"We need to give challengers a better chance of unseating incumbents, and it simply will not happen that Congress would vote to limit its own powers," he argued.

John Booth of Dallas is the co-founder of RestoringFreedom.org, a group campaigning for a convention to be charged with drafting an amendment that would demand that any increase in the federal debt be approved by a majority of state legislatures.

"This would take away the keys to the debt car," he said of his proposal.

Lawrence Lessig, a professor at Harvard law school, is one of a variety of prominent scholars campaigning for constitutional changes that would curb the dominate role of money in American politics. Mr. Lessig wrote the 2010 book, Republic Lost: How Money Corrupts Congress -- and a Plan to Stop It, which urges a national mobilization to achieve that end, a call that's been endorsed by such disparate figures as Mark McKinnon and Joe Trippi, consultants who worked on the campaigns, respectively, of former President George W. Bush and former Vermont Gov. and Democratic National Committee Chairman Howard Dean.

Mr. Lessig, in an unlikely partnership with Mark Meckler, a co-founder of the Tea Party Patriots, led a September conference at Harvard law school in which hundreds of scholars and activists of various political stripes spent a weekend discussing the questions and implications posed by the novel, though centuries-old, political possibility.

In a keynote speech, archived on the law school's Web site, Glenn Reynolds, a University of Tennessee law professor and author of the widely read blog, Instapundit, said the movement for a new constitutional convention was a reflection of the fact that "we have, in many ways, the worst political class in our country's history.''

In one conference panel, Sanford Levinson, the author of Our Undemocratic Constitution: Where the Constitution Goes Wrong (And How We the People Can Correct It), contended that that the current level of disaffection with Congress represented a threat to democracy. He said congressional approval numbers approaching single digits "raise questions on the basic legitimacy of our political system.''

Mr. Reynolds made a similar observation on the degree of civic estrangement, noting that a recent Rasmussen poll found that only 17 percent of those questioned agreed that the government had the consent of the governed.

Among the wide variety, and sometimes contradictory, amendments discussed at the Harvard event were calls for a shift to a popular vote for electing presidents, a balanced federal budget mandate, limits on money in politics in ways now deemed unconstitutional, the end of life tenure for federal judges and justices, a structure to ensure that the government could function after a devastating attack or catastrophe that wiped out the senior officials, and Mr. Reynolds' perhaps tongue-in-cheek suggestion to consider a "House of Repeal," a new body with an institutional bias in favor of shrinking government.

Mr. Meckler, the Tea Party activist, did not endorse the concept of a constitutional convention, but he bemoaned the fact that, in his view, the concept inspired irrational opposition from across the spectrum.

"You'll hear from the right that we'll end up with a Marxist country … hear from the left that they're going to take away all our rights," he says in his remarks on the Harvard Web site. "I hear this craziness from both sides."

Speakers at the conference, and figures in the persistent, if low key, national debate on a potential convention point to numerous unresolved questions on how it might function.

Lawrence Tribe, the prominent Harvard legal scholar, called Article V's terse language on convention procedures "dangerously vague."

Among the many questions raised by the potential proceeding are how its delegates would be selected, whether the convention could consider amendments beyond the subject matter of the original resolutions from the states, whether and how the delegates would be paid, and whether Congress or the courts would have the authority to resolve disputes that arose from their deliberations.

If, for example, a convention were called with the stated purpose of devising limits to money in politics, and if the delegates to that conference were to be elected, would the current state of the law bar outside cash in those delegate elections?

Mr. Labunski called that possibility "a matter of great irony and frustration.''

"The same interests active in influencing polities already would certainly be active in trying to make sure that delegates elected would not disturb the status quo,'' he said.

Mr. Levinson, the Texas scholar, favors choosing delegates by lottery, creating a kind of citizens' jury on the Constitution. Exactly how that would be accomplished is unclear, but he argued that a crucial advantage of a such a lottery is that there would then be "no elections to buy."

After reviewing some of those questions at the conference, Mr. Tribe observed that there were disagreements not just on their substance but on how to go about answering them. Noting the uncertainty on how broad the scope of a convention might be, he warned against, "putting the whole Constitution up for grabs."

That concern points to a phrase that recurs among criticisms of the convention concept -- that it might produce "a runaway convention," proposing broad, unforeseen changes in the U.S. governmental structure.

Nick Dranius, a scholar at the Goldwater Institute, and a strong proponent of the need for a constitutional convention, dismisses that fear. During a panel at the Harvard conference and in an essay on the institute's Web site, he underscored the fact that while a convention would be empowered to propose amendments, they could not go into effect unless ratified by three-quarters of the states, the same ratification process followed through the nation's history with amendments that originated in Congress.

"To get to 38 states, you've got to have something that sells on both sides of the aisle," he said.

Larry Sabato, the widely quoted University of Virginia political scientist, argued in his 2007 book, A More Perfect Constitution, that an Article V convention could be a valuable exercise for the country. In an e-mail exchange this week, however, he said, "I think there's only a slim chance we'll have one.''

"Too many people fear a runaway convention,'' he added. "and the constitutional hurdles to calling one are quite high [as they should be]. I see no real chance of such a convention in the foreseeable future."

Some proponents of the concept, however, see potential value in agitation in favor of a convention even if it never came to fruition.

Mr. Lessig suggests that the 17th Amendment, which instituted the Progressive Era reform of changing the election of senators to a popular vote, taking the power away from state legislatures, illustrates that dynamic. Congress acted on it, he noted, only when supporters were within one state of the votes needed to call what would have been the nation's first Article V constitutional convention.

Block News Alliance consists of The Blade and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. James O'Toole is a staff writer for the Post-Gazette.

Contact James O'Toole at: jotoole@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1562.