Term limits do little to oust Ohio lawmakers

Many skirt regulations by switching chambers

7/29/2012

COLUMBUS -- It's been two decades since Ohio voters amended their constitution to cap the number of consecutive years a state lawmaker can hold his office.

But today, five state representatives and a senator who were here in the General Assembly when the term-limits clock first started ticking are still here, their service uninterrupted as they've jumped from one chamber to the other and back again.

Two will have 30 or more years under their belts by the end of the current session.

"Term limits were a way that Ohio citizens decided to put some parameters on our elected officials," said Catherine Turcer of the government watchdog group Common Cause. "What they wanted was for local people to go to Columbus, represent their constituents rather than lobbyists and their party, and then come back home. … The musical chairs in which legislators serve in the Senate, then in the House, and then back in the Senate completely violates the spirit of that citizen legislator returning to the community."

But David Zanotti, president of the conservative Ohio Roundtable and a leader in convincing 69 percent of voters to support term limits in 1992, said the constitutional amendment was never meant to be the equivalent of a political death penalty.

"It's uninterrupted service, but it's not in the same office. That's very critical," he said. "When we passed term limits, there was gigantic criticism that we would be throwing out the good ones along with the bad ones. There would never be a veteran who could build up knowledge, that people would be forfeiting choices. … We've left the door open."

In all, 18 current state representatives and senators have served more than eight uninterrupted years in Columbus by making at least one jump between chambers.

Ohio and Michigan were among 15 states that used the voter-initiative process to enact legislative term limits during the 1990s. No state has gone down that road in more than a decade, and a few have seen their limits struck down by courts for various reasons.

Ohio shows its state senators the door after two four-year elected terms, a total of eight years. It pushes members of the House of Representatives out after four two-year terms, again eight years. There are no lifetime limits.

Up north

Michigan, however, is among six states that set lifetime limits -- two four-year Senate terms and three two-year House terms with lawmakers permitted to max out their eligibility in both.

Patrick Anderson, chief executive officer of Anderson Economic Group LLC in East Lansing, wrote the Michigan language dealing with legislative term limits that was adopted as part of Michigan's broader 1992 constitutional amendment. At the time, he was working for the late businessman Richard Headlee, father of the 1978 constitutional amendment in Michigan limiting government's ability to raise taxes without voter approval.

Michigan's lifetime limit prevents bouncing between chambers.

"That does somewhat bruise the idea of rotation in office," he said. "You are staying in the same branch of government for an indefinite amount of time, but to the extent that someone may actually leave behind the advantage of incumbency and contend before voters for a different office does maintain some portion of rotation of office."

The concept

He said term limits date to the Articles of Confederation of 1776, even if they did not survive in the U.S. Constitution of 1787. His portion of Michigan's 1992 amendment followed closely the 22nd Amendment to the U.S. Constitution ratified in 1951 after Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected to the presidency four times, flying in the face of the long-standing precedent set by George Washington, who limited himself to two terms.

"Thomas Jefferson wrote about rotation in office, the idea that a person who wished to serve in elected office could run based on life experience, be elected, serve, and go back and live under the laws that he had passed," Mr. Anderson said. "If he or she wanted to, they could pursue a different office so that they could not make use of the powers of incumbency or build up any monarchal or despotic privileges."

Philip Blumel -- president of U.S. Term Limits, the Virginia-based organization that largely relied on the citizen-initiative process in states such as Ohio to promote term limits -- said the organization prefers lifetime limits but is not wedded to them.

"Having term limits of any kind addresses the problem of rotation in office and competitive elections. That's the big picture," he said. "When we talk about lifetime or consecutive, we prefer lifetime but for secondary reasons. … It just gives more opportunity for citizens to participate on a level playing field."

Ohio and Michigan voters also overwhelmingly approved congressional term limits, but a U.S. Supreme Court ruling subsequently struck that down along with similar laws in 21 other states. The courts ruled that states could not impose limits on federal office.

Coming back

Rep. Rex Damschroder (R., Fremont) is among a relatively new breed of Ohio lawmaker who had to leave because of term limits and since has returned. Voters replaced him in 2003 with Jeff Wagner (R., Sycamore), who ran into his own term limit in 2010 and is now a Seneca County commissioner. Mr. Damschroder doesn't like the idea of some lawmakers sticking around by moving from one chamber to another.

"Make them sit out and go back into the private sector, just like me with my little airport," he said. "It forces you to get back out and make a living and deal with government from the other side of the fence. Term limits have been very positive. I was forced out. I took a boat and sailed across the Atlantic and back."

Mr. Wagner doesn't know if he will seek to return in six years, assuming Mr. Damschroder maxes out in his second round of eligibility.

"I'm a fan of term limits,'' he said. "The guy before me, Rex, was very popular and would not have been beatable … Term limits gave me a chance, and they gave a chance to the guy after me."

Sticking around

In 2000, when the first set of lawmakers maxed out their eight years, 45 of the 99 members of the state House of Representatives had to leave. The impact was more muted for the 33-member Ohio Senate because just half of that chamber appears on the ballot every two years. Six left in 2000.

But some simply swapped places, their legislative tenures, salaries, and contributions to their public pension plans never interrupted.

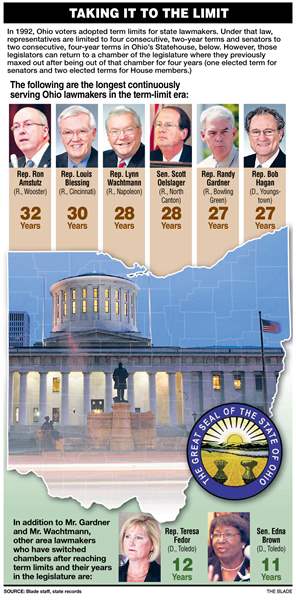

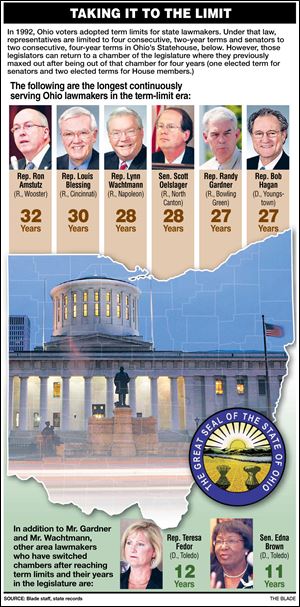

Occasionally, Rep. Randy Gardner (R., Bowling Green), closing in on 27 years in office after moving from the House to the Senate to the House, is challenged on his longevity in office. He carries with him a folder that, among numerous other papers, contains a 1999 newspaper quote from Mr. Zanotti defending the practice of switching chambers.

That quote may come in handy again this year as he asks voters of Wood, Ottawa, Erie, western Lucas, and most of Fulton counties to send him back to the Senate to replace Sen. Mark Wagoner (R., Ottawa Hills), who opted not to seek a second term.

"I think in an era of term limits that there is some advantage for having veteran legislators at the Statehouse, but I truly believe each individual House or Senate race is its own contest," he said. "The first question shouldn't be how long a legislator has been there, but is that the candidate who will better serve the people of that House or Senate district."

Rep. Ron Amstutz (R., Wooster), chairman of the powerful House Finance and Appropriations Committee, is dean of post-term limits legislating with 32 consecutive years in the General Assembly. He already had 20 years under his belt when the first impact of term limits was felt in 2000. Voters then sent him to the Senate and then back to the House in 2009.

He has been presiding over a series of hearings to educate committee members when it comes to school funding. In this age of term limits, many lawmakers were not here when the Ohio Supreme Court repeatedly held the state's method of funding K-12 education unconstitutional.

"We do have some newer members," he said. "They do their homework, and some have read the DeRolph decisions. I wouldn't suggest we don't have tremendous talent. A lot of them are very talented with their own life experience, even if they don't have the legislative component background."

Although never pushed out by term limits, House Speaker Bill Batchelder (R., Medina), at 36 years in the House without a day in the Senate, is the most senior member of the chamber. He voluntarily left after 30 years for a judgeship two years before term limits would have forced his hand in 2000. He returned in 2007.

While there seems to be little appetite among lawmakers to ask voters to repeal term limits, there have been discussions about asking for an extension to possibly 12 years.

"I don't have any suggestions on the number of years," Mr. Batchelder said. "I have no idea whether the public would support it. They killed an extension of judicial service in the last election."

Quality candidates

The lack of a longer-term future for most rank-and-file lawmakers has posed a challenge to recruiting quality candidates and can make it more difficult to keep them if another opportunity comes up elsewhere in government, he said.

Rep. Lynn Wachtmann (R., Napoleon) has nearly 28 years in the General Assembly, resetting the term-limits clock with moves from the House to the Senate and back again. For now, Mr. Wachtmann said he's inclined to let the clock run out after 2014. "I think, frankly, it's time for guys like me to move on," he said, noting that he's seen colleagues who stay so long that their health declines in office. He described term limits as a mixed bag but said he's been impressed with the new blood that has joined the Republican caucus.

Other lawmakers with more than two decades of uninterrupted service include Rep. Lou Blessing (R., Cincinnati) with 30 years, Sen. Scott Oelslager (R., North Canton) at nearly 28 years, and Rep. Bob Hagan (D., Youngstown) with 27 years.

Voters last year sent Rep. Teresa Fedor (D., Toledo) back to the House where she started her political career after term limits forced her out of the Senate. She's been in the General Assembly 12 years.

"I think term limits puts everyone at a disadvantage as far as trying to focus on one single issue and make a huge impact," she said after seeing her anti-human-trafficking legislation passed. It had been in the works for seven years before reaching Gov. John Kasich's desk.

Voters also promoted Edna Brown (D., Toledo) from the House to the Senate in 2010 after she'd exhausted her eligibility in the lower chamber.

Mr. Anderson said Michigan's experience with term limits has been positive, although legislators have faced the same criticism there as here. "The variety of people in office has grown," he said. "The share of legislators with some practical experience has increased. The arrogance that comes with unlimited terms has diminished somewhat. However, term limits were not intended to nor have they eliminated inherent vices of human beings such as avarice, ambition, and desire to politically fund-raise, nor have they stopped politicians from sending exaggerated, misleading, and bogus press releases about their accomplishments."

"The major criticism about term limits is they haven't changed human nature entirely," Mr. Anderson said. "Politicians still do embarrassing things."

Contact Jim Provance at: jprovance@theblade.com or 614-221-0496.