Obama inaugural draws on nation’s best orators

1/22/2013

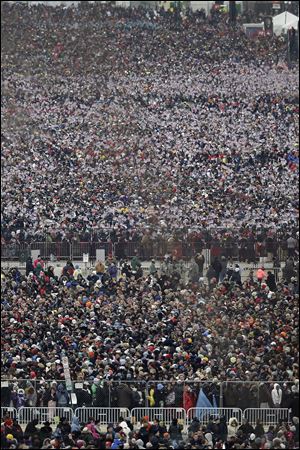

President Obama waves after his inaugural address while Vice President Joe Biden applauds at the ceremonial swearing-in outside the U.S. Capitol on a cold day.

With a bow to the past, an arc toward the future, and a steady eye on his place in history, President Obama opened his second term with a call to make the struggles of the middle class, the immigrant, the striving, and the vulnerable the American cause in the second decade of the 21st century.

No modern inaugural address ever was as punctuated with subtle references to the American canon as this one, with repeated references to the preamble of the Constitution and with carefully shrouded allusions to Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and John F. Kennedy. Embedded in Mr. Obama’s speech was a trove of the enduring remarks of three of the finest verbal craftsmen of the American idiom.

But equally prominent in his remarks were references to the pathfinders of American freedom, the men and women who expanded the American electorate; who broadened American culture, and who, with their challenge to the status quo, enlivened and enriched the mainstreams of American life.

No president who preceded Mr. Obama would have placed in the same sentence the struggles of Seneca Falls, where an 1848 convention and a Declaration of Sentiments began the women’s movement; the confrontation at Selma, the Alabama county seat whose bridge in 1965 became a bloody symbol of the civil-rights movement, and the 1969 riot at Stonewall, the gay bar in New York’s West Village that became a symbol for the fight for gay rights.

And by saying that it was America’s “task to carry on what these pioneers began,” Mr. Obama identified these onetime rebels with the insurrectionists who began the American Revolution and the American experiment — and perhaps not with their rebellious heirs on Capitol Hill who hold the Obama presidency and the Obama proposals hostage.

Overall, the Obama speech set forth the President’s vision of an America that preserved the social insurance programs of his progressive forebears Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Lyndon Baines Johnson even as it attacked the federal budget deficit and brought comity to the Capitol, where ferocious fights over spending marred the President’s first term.

These divisions similarly threaten his second term, when the question of the future of entitlements such as Roosevelt’s Social Security and Johnson’s Medicare almost certainly will be engaged.

Throughout the Obama vision are the sometimes irreconcilable values of unity and diversity — values encapsulated, and reconciled, in the phrase on the front of the U.S. Great Seal: E pluribus unum. For Mr. Obama used his remarks Monday to set out a national path and, at the same time, secure national unity.

Inauguration Days are occasions for high hopes and high rhetoric, and unity on Capitol Hill might be a barrier too high even for days like Monday.

“My fellow Americans,” he said, “we are made for this moment, and we will seize it— so long as we seize it together.”

The American political class has done almost nothing together in the Obama years without titanic struggle, and sometimes, including the landmark Obama overhaul of the health-care system, without any Republican votes whatsoever. Even so, the President seemed to be saying, the nation must move forward, sometimes accepting small progress when perfection is unattainable.

“We must act,” he said in an allusion to Kennedy’s 1961 inaugural address, “knowing that today’s victories will be only partial, and that it will be up to those who stand here in four years, and 40 years, and 400 years hence to advance the timeless spirit once conferred to us in a spare Philadelphia hall.”

The Obama speech may have provided few quotes for the American scrapbook — the President relied, perhaps too much, on his predecessors for stirring sentiments — but this was an inaugural address that was artfully and deliberately constructed. He portrayed the American story as a “bridge” between ideals of the Declaration of Independence (specifically, that “all men are created equal”) and what he called “the realities of our time,” adding:

“For history tells us that while these truths may be self-evident, they have never been self-executing; that while freedom is a gift from God, it must be secured by His people here on Earth.”

That excerpt served two purposes on a frosty Washington noon hour. It affirmed, as Lincoln had done, that the goals of the Declaration of Independence, which have no basis in law, were in fact the goals of the Republic created 13 years later by the Constitutional Convention.

And it also tied Mr. Obama to Jefferson, who wrote the Declaration, and to Kennedy, who concluded his own inaugural address more than a half century ago by saying that “here on Earth, God’s work must truly be our own.”

Mr. Obama drew heavily on Lincoln, the first Illinois president and the chief executive he says he most admires, speaking of a “government of, and by, and for the people” (Gettysburg Address, 1863).

Kennedy and Lincoln served precisely a century apart, and it was to those two presidents Mr. Obama turned for his trumpet call at the conclusion of his address. Kennedy had said in 1961 that “the devotion which we bring to this endeavor will light our country and all who serve it — and the glow from that fire can truly light the world.” Lincoln ended his second inaugural in 1865 by pleading, “let us strive on to finish the work we are in.”

The Obama version is an amalgam of the two timeless remarks, updated for our own time:

“Let each of us now embrace, with solemn duty and awesome joy, what is our lasting birthright. With common effort and common purpose, with passion and dedication, let us answer the call of history, and carry into an uncertain future that precious light of freedom.”

All this may on the surface seem at odds with the notion that while only 44 men have served as chief executive, every president is an American original. But for a president who is decidedly not like the others, it may be especially important to seem and sound like his predecessors, particularly like those whose soaring rhetoric made the American heart soar.

At base, Barack Obama may indeed be like other presidents. He wants to be remembered, and quoted, generations from now. If he is, it may well be because of his belief in “that precious light of freedom”— his phrase, completely — that has illuminated the American way, in olden times and in our own.

Block News Alliance consists of The Blade and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. David M. Shribman is the executive editor of the Post-Gazette.

Contact David M. Shribman at:

dshribman@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1890.

Follow him on

Twitter at ShribmanPG.