ATHLETES AT PUBLIC UNIVERSITIES

Union concept carries wave of complexities

State laws could tilt competitive balance

6/1/2014

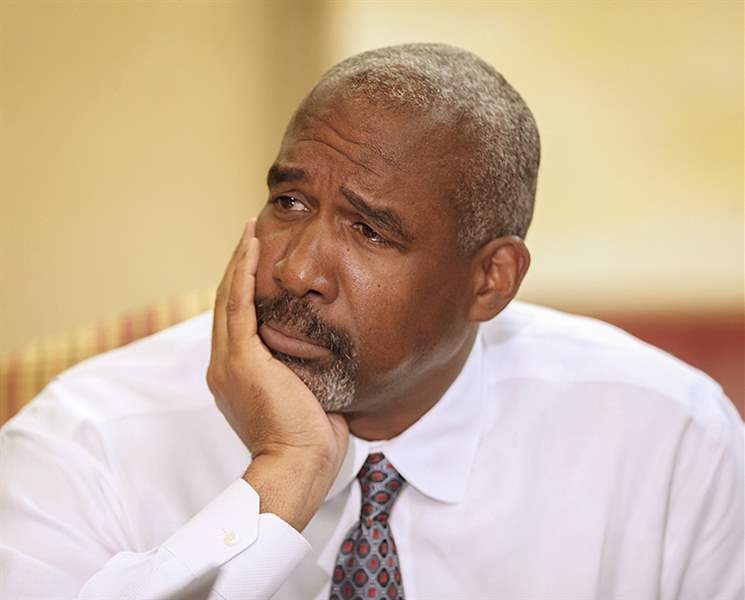

Gene Smith of Ohio State says he favors reform. But, he adds, ‘if you turn it into an employer-employee relationship, it changes everything.’

ASSOCIATED PRESS

Gene Smith of Ohio State says he favors reform. But, he adds, ‘if you turn it into an employer-employee relationship, it changes everything.’

O’Brien

COLUMBUS — When a federal board recently ruled that football players at Northwestern University could form a union, it was a historic but limited decision.

Kingston

The bigger question is what the landmark case means for NCAA athletes at public colleges.

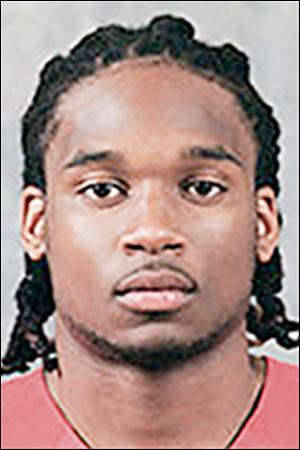

Roby

Could the union movement ever come to Ohio State, where quarterback Braxton Miller is compensated with a scholarship valued at $22,418 per year as the star of a football team that generated $61 million in revenue last year? Could the football and men’s basketball players at the heart of a $16 billion industry some day collectively bargain for improved benefits at Penn State and Wisconsin?

It all depends on the state, where vastly varying political climates and labor laws could open a tangle of complications — including questions of competitive balance if, say, a star recruit were required to join a union at OSU and unable to at Michigan.

“In almost every way, there is a can of worms that is going to be opened up from this,” University of Toledo law professor Geoffrey Rapp said. “That doesn’t mean it’s a bad idea. It just means there are going to be repercussions of a wide variety of forms.”

If the National Labor Relations Board upholds later this summer a regional NLRB official’s ruling that Northwestern’s football players are employees and thus able to unionize, the precedent likely would apply to all private schools. Meanwhile, the public schools that make up 108 of the 125 NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision members are beholden to their states.

The extremes range from Connecticut, where lawmakers have proposed legislation that would give university athletes the right to unionize, to the 24 right-to-work states, where union membership cannot be mandatory in a workplace, to states such as Alabama and Texas, where public employees have no rights to collective bargaining.

Ohio is somewhere in the middle, even as the state’s Republican-controlled House passed a measure in April decreeing that players are not university employees. A spokesman for the Ohio AFL-CIO said the federation would back a union push at OSU and other state schools.

“Anytime there are employees out there that are in need of representation, a voice on the job, I think we’re going to lend our support,” Ohio AFL-CIO political director Jason Perlman said, “no matter what the political ramifications or the position they hold.”

He added, “I look at it like any other business. When you have few with total control, usually it self-destructs at some point, and those who are actually performing the work don’t have a voice in making sure the product — in this case football — stays viable and the employees can stay healthy and have some security. I don’t think it’s any different than an auto plant or a steel plant or a coal mine.”

Opposition

College administrators are almost universally against the union concept, hoping instead that widespread reform will keep intact a semblance of the traditional amateur model.

Among them is Ohio State athletic director Gene Smith, who has found himself in the crosshairs of a system under siege. When he received an $18,000 bonus because Buckeyes wrestler Logan Stieber won a national title earlier this year, the news went viral — the reward for an individual feat seen by some as a stark symbol of a backward arrangement where everyone but the athletes profits. (Though Mr. Smith’s bonus was in his past contracts and incentives tied to athletic success are common nationally, he said the backlash will lead him to re-evaluate the structure of his deal “because of the optics.”)

Mr. Smith, 58, wants to update, not upend the NCAA. A Cleveland native who attended Notre Dame on a football scholarship, he believes in the best possibilities of college athletics. At Ohio State, the football and men’s basketball program fund opportunities for athletes in 34 nonrevenue sports.

“If you turn it into an employer-employee relationship, it changes everything,” Mr. Smith told The Blade. “[Oklahoma football coach] Bob Stoops said it best: ‘Then I could fire them.’ If you’re negotiating with a union on what the benefits are on the other side of the table, there are going to be stricter demands on the relationship. I just believe that there’s a better way to solve the problems.”

That includes a push to give the biggest and richest schools the autonomy to use their massive resources as they see fit. Mr. Smith favors a proposal — expected to be approved by the NCAA in August — that would give the 65 members of the Atlantic Coast Conference, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-12, and Southeastern Conference the ability to provide athletes with unprecedented benefits, including enhanced medical care and insurance and a few thousand extra dollars per year. The stipend would cover the difference between the value of a full scholarship and the practical cost of attendance. (OSU, for instance, calculates the cost as $3,340 for an Ohio native and $4,786 for an out-of-state student.)

While Big Ten Commissioner Jim Delany proposed a $2,000 annual stipend to help scholarship athletes in all sports cover their full expenses in 2011, the measure had little chance in a vote of 351 NCAA Division I schools — most with far fewer resources than the power leagues. The still-to-be defined latest proposal would cost between $500,000 and $1 million per school, veritable pocket change for top programs. Last year, Ohio State earned $124 million in revenue and spent $123 million while Michigan pulled in $123 million and spent $111 million, according to federal data.

“Cost of attendance, health care, what Northwestern players are talking about, I agree with them 100 percent,” Mr. Smith said. “If an athlete gets surgery in their senior year, then graduates and goes to California and two years later, they have surgery on the same leg, we can’t pay that. We can’t create some type of insurance policy to protect injuries that may occur as a result of playing, and I’m a proponent of that. There’s a way to solve these issues.”

The other conferences, meanwhile, are now forced to reconsider their path. University of Toledo athletic director Mike O‘Brien is opposed to college unions but in favor, he said, of “whatever can be done to better the environment for the student-athletes.” Though UT navigates a tight budget — the department came out even last year after distributing $23.7 million in revenue among 15 varsity sports — Mr. O’Brien is in favor of Mid-American Conference schools paying athletes a cost-of-attendance stipend.

“It’s something that each institution is going to have to look at,” he said. “But given the fact that we recruit against various conferences, obviously we have to look at that and in turn be in favor of it.”

Bowling Green State University athletic director Chris Kingston preferred not to discuss specific proposals, saying, “I’m in favor of all of my coaches and all of my student-athletes having everything they need and a lot of what they want in order to compete for and win championships.”

Cash questions

So what is enough? Keeping in mind the Title IX mandate that financial aid available to male and female athletes be “substantially proportionate,” how much compensation is fair for a major-conference football or men’s basketball player?

At Ohio State, for instance, an out-of-state scholarship football player receives a grant-in-aid valued at $38,138 that covers tuition, books, a stipend for housing, and per recent NCAA legislation, unlimited on-campus meals and snacks. The athletic department also foots the bill for 380 athlete campus-parking permits and annually distributes several hundred thousand dollars in need-based aid from the NCAA’s Special Assistance Fund.

The fund has covered everything from braces for basketball star Evan Turner to helping the family of former defensive lineman Nader Abdallah after their New Orleans home and grocery store were destroyed by Hurricane Katrina.

“I remember [Abdallah] had tears in his eyes,” Mr. Smith said. “He was going to drop out of school because his family had lost everything. We were able to bring his family here, put them in the Holiday Inn, give them a pier diem, and get them back on their feet.”

Beyond that, many players from low-income families receive up to $5,645 per year in Pell Grant aid.

Athletes at Ohio’s eight public Football Bowl Subdivision — FBS — colleges received more than $4 million from the federal program last year, according to information provided through open records requests. Ohio State had 57 football players receive a total of $245,359 in Pell Grant aid and 175 athletes in all receive $736,342. Toledo had 57 football players receive $258,771 and 122 athletes overall receive $509,209.

The Blade also sought Pell Grant data from the University of Michigan. The school asked for two extensions before denying the request, citing a subsection in the Michigan Freedom of Information Act and federal privacy laws. The same request made to Michigan State was fulfilled within a week.

Through a spokesman, Michigan athletic director Dave Brandon declined to comment for this story.

The road ahead

For now, few agree on the best course for college athletics.

While many players express faith in the status quo — “it just kind of seems silly to want to be unionized because we get a lot of stuff that people don’t get,” OSU defensive lineman Michael Bennett said — others want a bigger voice.

Former Ohio State star cornerback Bradley Roby said he “definitely” felt like an employee playing college football — the distinction at the center of the Northwestern case. Kain Colter, the ex-Wildcats quarterback spearheading the union movement, testified at an NLRB hearing that players work an average of 40 to 50 hours per week. He said the time commitment led Northwestern to steer him away from a premed track to less strenuous courses.

“How these colleges are running football programs now, it’s just like the NFL,” Roby said earlier this year. “It’s about results, it’s about winning. That’s what the game is about. ... Classes, working out, performing week in and week out. You’re doing all that and then you’re coming home and don’t have much to eat.

“You can’t take anybody out to go get food or go to the mall and get some new shoes. It’s like, ‘Wow, where’s all this money going?’ Not in my pockets. I sympathize with the [Northwestern players].”

Mr. Perlman, the Ohio AFL-CIO official, said he has heard from several former college athletes in favor of player unions.

“To think college football is going to go away because of this is just silly,” he said. “It may change. Players may have more security, and maybe players in their contract would have things we don’t agree with or not like because they can’t just be suspended for whatever team rule or whatever it may be or for no cause.

“But giving them the ability to organize a union is not saying that you have to pay them a ton of money and the scholarship shouldn’t be considered into that. It just means they have the ability to sit down across from their athletic director and work out rules.”

The future of the union push remains murky, even at Northwestern, where football players voted in April on whether to exercise their right to organize. (The vote will not be counted until — and if — the NLRB upholds the ruling that they are employees.) And for public schools in states such as Ohio, the threat remains distant. Experts said the Ohio State Employment Relations Board is unlikely, for now, to defy the House and declare any university players to be employees.

“The majority of the members are the same party as the governor, so the majority are Republicans while the majority of the NLRB are Democrats because of the President,” said UT professor Joseph Slater, one of the nation’s leading voices on public sector labor law. “So if people were to stick to their stereotypes of what their ideologies are, you would think it would be less likely they would extend these rights to college athletes.”

Still, change is coming, the big money giving way to bigger complications.

“I’ll never back away from the fact that football and men’s basketball here and other places generate revenue and support a large number of other student-athletes,” Mr. Smith said. “That’s the collegiate model. It helps our student-athletes in a significant way. Many of them would not be able to go to college were it not for sport. I’m a big believer that we sometimes miss the point when we don’t focus on the other sports.

“But that’s understandable. We created this. Our culture created this.”

Contact David Briggs at: dbriggs@theblade.com, 419-724-6084 or on Twitter @DBriggsBlade.