FLOC leader, British allies take fight for migrant workers to N.C.

Group pressures tobacco firm to improve camp conditions

7/20/2014

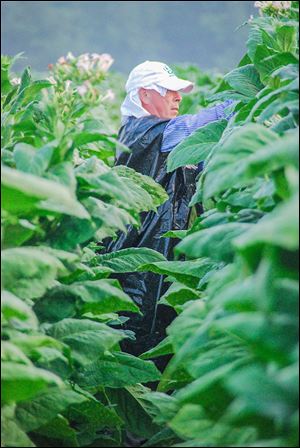

Baldemar Velasquez, the founder and president of FLOC, labored on a North Carolina tobacco farm in 2008.

CHRISTIANA VELASQUEZ

Baldemar Velasquez, the founder and president of FLOC, labored on a North Carolina tobacco farm in 2008.

Ian Lavery’s desire to stand up for workers started in the coal mines of North East England and will take him to the tobacco fields of North Carolina, where he and a fellow member of the British Parliament will travel this week on a fact-finding mission organized by a Toledo-based farmworkers union.

Mr. Lavery and Jim Sheridan will visit the southern state during the high heat of late July, when tobacco workers toil in fields and live in migrant camps that the Farm Labor Organizing Committee contends can be unsanitary and poorly equipped.

The union planned the rare human rights visit by foreign representatives to the heart of tobacco country. The two Labor Party members will meet U.S. Rep. Marcy Kaptur (D., Toledo) and FLOC president and founder Baldemar Velasquez.

Exploitation occurs around the world, and the trip highlights that abuses also occur in the United States, said Mr. Lavery, who worked as a miner, served as a union leader, and was elected a member of Parliament in 2010.

“I want to see it firsthand ... and then see if there’s anything at all that can be done to help these people,” he said during a phone interview.

On Saturday, the contingent will visit the union’s field office in Dudley, N.C., go to several camps, and attend a forum during which laborers will speak about how they are treated. The next day, the two members of Parliament and Mr. Velasquez will meet in Raleigh with church and advocacy groups. Mr. Velasquez and Mr. Sheridan plan to go to Washington early the following week to see leaders of the AFL-CIO, which supports an ongoing FLOC campaign to sign up tobacco farm laborers.

“I think there’s regular exchanges between U.K. and American politicians, but I don’t think anything like this has ever happened before,” Mr. Sheridan told The Blade, also by telephone.

The effort is part of the union’s attempt to improve what it alleges are substandard working and living conditions for farm workers — a situation it says Reynolds American Inc., and its biggest shareholder, British American Tobacco, have the power to correct.

In December, Mr. Velasquez traveled to London and met with Parliament members to discuss the human rights of tobacco farm workers and later invited officials to visit North Carolina.

Big tobacco

FLOC wants to focus international attention on the situation and pressure British American Tobacco, which owns about 42 percent of Reynolds American, the parent company of R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. Reynolds is a major purchaser of tobacco in North Carolina, where the union has a foothold through a collective bargaining agreement with the North Carolina Growers Association.

U.N. officer Rhys McCarthy, left, FLOC chief Baldemar Velasquez, and Parliament members James Sheridan and Ian Lavery meet in London about tobacco workers’ plight. During the trip in December, Mr. Velasquez invited them to North Carolina.

FLOC aims to organize thousands of tobacco farm workers and reach an agreement similar to the one it struck with workers, Toledo-area growers, and Campbell Soup Co. — a tactic it replicated a decade ago with Mt. Olive Pickle Co. in North Carolina.

Providing workers with good housing and better wages costs money, and corporations such as Reynolds should pay for that, Mr. Velasquez said.

“It makes no sense for us to fight with the farmers over a bone like two dogs ... but to go up the supply chain to try to get some cash infused from the top down to the bottom so that people can earn a fair day’s pay for a fair day of work,” he said.

Reynolds’ position

Reynolds officials would not agree to be interviewed about farm labor issues. Spokesman Bryan Hatchell declined to answer questions submitted by email; he cited a lack of time to respond because of last week’s announcement that Reynolds, the nation’s second-largest tobacco company, will acquire the third-largest, Lorillard Inc.

Reynolds contends that because it doesn’t grow tobacco or employ farm workers it doesn’t control their pay or housing. The company has undertaken “significant efforts” — such as training programs for contracted growers and donations to improve migrant housing — aimed at helping suppliers “do the right thing for the people who play an important role in our supply chain,” according to an online statement.

Migrant camps

In North Carolina, Mr. Velasquez said some tobacco farm workers sleep in camps with no windows for ventilation, and facilities can lack places to bathe or do laundry. Clean clothing and showers are critical because workers absorb nicotine through their skin when handling tobacco. Symptoms of green tobacco sickness include nausea, headaches, vomiting, and fatigue, according to a 2011 report by FLOC and Oxfam America.

FLOC plans to take visitors to several labor camps where undocumented workers live and introduce them to workers who will testify about the conditions.

“I think they will be appalled,” Mr. Velasquez said.

He said conditions are generally better at farms that employ those with guest worker visas, a program that allows people from other countries to legally work in the United States. The North Carolina Growers Association is the nation’s largest user of the program, and it guarantees a $9.87 minimum hourly rate, said Executive Director Stan Eury.

Baldemar Velasquez, left, meets his roommates, nicknamed El Nino and El Caballo, in a labor camp at a tobacco farm in North Carolina. In July, 2008, in brutal heat and humidity, he lived and labored with about 14 migrant workers. ‘My feeling is that if I’m going to represent somebody, I better do the work that they’re doing,’ he said.

Undocumented workers typically make the minimum wage of $7.25, sometimes less. They are often afraid to complain about conditions for fear of retaliation, Mr. Velasquez said. Many of the workers are illegal immigrants from Mexico.

The growers association provides about 7,800 workers to help with numerous crops, from tobacco to sweet potatoes and cucumbers. The workers reside in hundreds of camps at farms throughout the state.

“Our guys are 100 percent in compliance, and so we don’t have much control or comment over what everyone else does,” Mr. Eury said.

The North Carolina Department of Labor inspects migrant farm housing annually. It checks for cleanliness, smoke detectors, and hot and cold running water, among other items. A minimum of one toilet is required for every 15 people of the same sex.

In 2013, it issued certificates to 1,478 housing sites, with a total number of 17,887 beds. Last year, it found 10 unregistered camps, according to the agency’s annual report.

“The biggest complaint we get from the advocates is about the substandard camps,” said department spokesman Dolores Quesenberry, who said the agency has no comment on the upcoming visit. “If they see something, we would hope that they would call us and let us know.”

The living and working conditions of farm laborers are mostly hidden from public, said Miss Kaptur, who will accompany the group on Saturday. She said she’s concerned about workers who “have so little footing in our economic system” and respects Mr. Velasquez’s work. In 2007, she accompanied FLOC to Mexico, following the murder of one of its field organizers.

An opportunity

The North Carolina visit is a novel opportunity to shine binational attention on the labor situation.

“People of conscience have to inform and have to awake the rest of society,” Miss Kaptur said, adding that if the majority of Americans “understand a situation that is truly unjust, they will correct it.”

Upon returning home, Mr. Sheridan hopes to meet with leaders of British American Tobacco and share what he saw with U.K. news outlets.

“If people are working hard then they should reap the rewards. So hopefully Ian Lavery and I can bring some sort of focus to what’s going on in North Carolina,” he said.

Mr. Sheridan, who previously worked in Glasgow shipyards, is the chairman of the Unite the Union Parliamentary Group. Unite is Britain’s largest union.

Earlier this year, he and Mr. Lavery were among 45 Parliament members to sign a resolution calling attention to “onerous conditions faced by migrant farm workers in the tobacco fields of North Carolina and the American South.” It states that Reynolds refuses to grant workers freedom of association and calls for British American Tobacco to “use its influence” to help reach an agreement with FLOC.

Contact Vanessa McCray at: vmccray@theblade.com or 419-724-6065, or on Twitter @vanmccray.