Anniversary rekindles memories of storm

1/26/2003

Getting around in Toledo's Colony area near Monroe and Oatis streets was easier when skis and sleds were used.

blade

Hanifan: She works for a New York advertising agency.

Happy Birthday, Susie Snowflake.

A quarter-century ago, as a deadly blizzard ravaged the Midwest, you slipped into the world early in the morning on Jan. 28, 1978, in the semi-darkness of a bedroom near Waterville.

It's not that your mother chose it that way. But wind gusts that topped 50 mph had created drifts up to 16 feet that swallowed vehicles and even some houses. The hospital was now a white-out world away.

As your father held your mother's hand and a back-up generator struggled to light two bulbs, one of the paramedics - who just arrived by snowmobile - quipped: “If it's a girl, call her Susie Snowflake.”

It was a sweet name, and a sharp contrast to the vicious storm that struck Ohio and parts of the Midwest and the Ohio Valley on Jan. 26-27, 1978.

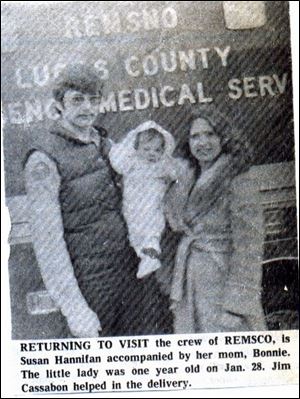

A newspaper clipping recalls the Hanifans' reunion with an EMT a year after the storm.

In the end, what meteorologists labeled as an incredibly rare “severe blizzard,” killed 61 Ohioans, including nearly a dozen in northwest Ohio. It was the Toledo area's worst blizzard in history: The Blizzard of '78.

A combined official snowfall of just over 13 inches paralyzed emergency services, shut down highways, stranded motorists in a zero-visibility nightmare, and plunged much of the state into darkness and cold. Nearly 30,000 area households served by Toledo Edison Co. were reported without power.

“It was just scary,” said former coach Darrell Hedrick, whose Miami University basketball team had beaten the Rockets hours earlier at the University of Toledo. He was jerked awake on the ride home when the bus ground to a stop as they left northwest Ohio.

The bus driver later suffered a stress-related heart attack. The team spent the night in a city jail.

“The snow was piled high,” the former coach said, “and it just kept coming and coming and coming.”

In rural Lucas County, Jim Sautter pushed into the oncoming wind to the woodshed 150 feet away from his powerless home where his wife huddled with their 3-year-old son and 6-week old daughter.

“I couldn't see my house once I got 20, 25 feet outside the door,” he said. “I couldn't see where I was going. I just walked into the general direction.

“When I turned around I couldn't see my footprints.”

---------------

What was recorded as the worst winter storm ever for Ohio was really the violent collision overhead Jan. 26, 1978, of two rather benign, low-pressure systems - one moving in from North Dakota, the other from the Gulf of Mexico.

On the second day of the Blizzard of '78, traffic on Heatherdowns Boulevard remained frozen by incapacitating snow that drifted over city streets.

Weather experts had seen the two fronts heading this way the previous day, but believed they'd miss each other. The North Dakota system was to sweep harmlessly north of Ohio, while the southern system was to creep into the state, bringing some harmless moisture.

Temperatures hovered above freezing on Jan. 25, making the precipitation more like spring rain.

“I laughed at the time,” recalled Marj Mulcahy, a registered nurse at Toledo Hospital. “It was raining and raining hard, and I thought you couldn't get change that drastically that fast.”

But meteorologists saw something much more menacing. Both systems had veered off their predicted courses and were on a collision course.

Most of Ohio crawled under the covers that Wednesday night under a cold, almost spring-like rain - many not hearing the forecasters' warnings at 9 p.m. that a blizzard was imminent.

“We knew this was a big one,” said Martin Thompson, then a young meteorologist technician assigned to the Mansfield office of the National Weather Service.

But even those who predicted a blizzard and watched as the winds began to pick up speed late into the night underestimated the wrath of the systems as they crashed into each other around midnight.

In an extremely rare and dangerous dynamic, the two systems twisted together to create a “severe blizzard.” It drove the mercury to below zero, solidified the rain into a coat of ice, and changed the rain to snow.

Mr. Thompson, figuring he would be stuck at the office for several days, packed his bags before he left for the office. But he was too late. Stinging wind and horizontal snow drove him back inside his front door.

Vicious gusts up to 100 mph thrashed much of the state, driving the wind chill to 60 degrees below zero and building snow drifts that consumed vehicles and rose as high as small buildings.

The phone rang at Donald Shanteau's home at 3 a.m. Toledo's former safety director remembers the hour-long crawl in his 1977 Plymouth Fury to the downtown fire station from his West Toledo home.

The snow was already bumper-high in places, and the slits of light from his headlights picked up the snow whipping across the roads.

“It was the old saying: `It's not snowing hard until it's snowing sideways,'” he said.

Getting around in Toledo's Colony area near Monroe and Oatis streets was easier when skis and sleds were used.

Jim Marshall, today the head of the local history department at the Toledo-Lucas County Main Public Library, had a meeting that morning at the library, but he got a 6 a.m. phone call at his Secor Road apartment telling him it was canceled.

“I looked outside,” he said, “and realized the only way out was to jump from the balcony.”

Those who dared venture outside were stranded along the expressways and side roads. Highways in Ohio's eight northwest counties were closed.

It wasn't until days later that a military helicopter sat down on U.S. 23 near Central Avenue and Mr. Shanteau hopped out with a screwdriver and measuring tape. The ice on the roadway, he learned then, was 8 inches thick.

For the first time in history, the Ohio Turnpike closed. A snow plow operator was found dead near his stalled truck in Wood County.

The National Weather Service in the coming days would record 61 weather-related deaths throughout the state - crushed in buildings that crumpled under the weight of the snow, and freezing in fields, near stalled vehicles, and in their own homes.

As the isobars on the national weather map closed into tight, ugly loops over Toledo, eerie green lightning flashed in the clouds overhead.

Utility lines dropped. Patches of homes and street lights flickered and went dark.

The work day began that Thursday, but left unmanned, stores, restaurants, and offices remained locked and empty.

Police and fire and hospital shifts were skeletal and chauffeured into work on snowmobiles.

It wasn't just that Mother Nature dumped so much snow. It was the fury in which she spat out everything: wind, ice, snow, and stinging, bitter cold, Toledo police Capt. Mike Murphy said.

“Our street looked like a maze they test mice in. It was just tunnels in the snow,” Captain Murphy said. “You didn't go out for a while. You didn't dare.”

When he eventually got to work, he said, “it was very quiet. There was very little being reported, except emergency calls of people stranded.”

---------------

By the end of the day of Jan. 27, what appeared to be powdered sugar icing - with a treacherous layer of ice underneath - slathered most of the Midwest.

Susie, it was then that your mother felt the first pains. Certainly, you were on the way. Emergency help, however, wasn't so certain.

Two young paramedics on their way to your home aboard a snowmobile dumped into a snowbank in the pitch dark, losing their medical equipment.

At your home, two tiny bulbs flickered while a wood stove kept the temperature just above freezing. Down the road, your aunt Kimberly Hertzfeld, who'd just finished her nursing training, began the bone-chilling, quarter-mile walk to your mother's side.

“It was ... our third child,” recalls your father, John Hanifan. “Our families had a history of delivering fast, so on the first two births, I figured I'd better pay attention. And it's a good thing I did.”

At 1:42 a.m. on Jan. 28, Susan “Snowflake” Kimberly Hanifan, you wiggled into the world.

Your father used clothespins to clamp your umbilical cord and the paramedics and your aunt joked with your mother about your name.

A short time later your mother, Bonnie, developed potentially lethal complications.

To get your mother to a hospital, a tractor owner hooked onto a Chevy Suburban in the icy dark of the early morning on the 28th and dragged it through shoulder-high drifts over what was the road from their house.

“It was like going down a bobsled chute,” your father recalls. “We'd bump against drifts and ricochet from one side to another.”

Your mother recovered, of course. And Susan Hanifan went on to become a production assistant for a New York advertising agency.

Most of the region recovered as well.

As day broke on the 28th, residents began to burrow out of their homes. Some rigged up sleds with boxes to get groceries. Others dusted off skis.

The two-day winter blast that dumped nearly a foot of snow had shattered routines as well as records. Among other things, the worst blizzard ever had produced the lowest barometric reading recorded in Ohio to that point.

The storm was blamed for $60 million in “lost production and livestock deaths,” according to the National Climatic Data Center.

For years to come, the slightest prediction of a significant snowfall would send residents scrambling to the grocery stores, where they'd clear the shelves of milk and bread.

But Ms. Hertzfeld said the Blizzard of '78 also taught many people that what they consider necessities - electricity, for example - are really conveniences. “It takes something like that,” she said, “to prove that we really are survivors.”