Perrysburg native co-authored Rose s book

2/10/2004

Rick Hill says he got to know Pete Rose pretty well in the 31/2 years they worked together, and that he believes the former All-Star is telling the truth: I feel very comfortable in the information Pete s given me.

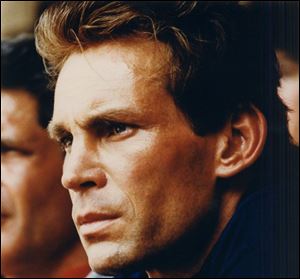

Rick Hill portrays a jail guard in the Jim Carrey movie Liar Liar.

In My Prison Without Bars, Hill partners with Pete Rose who, while banned from baseball since 1989, had steadfastly guarded the fact that he bet on the sport while managing the Cincinnati Reds.

“I wasn t so surprised at what he did,” Hill said. “My hook into this story was to try to find out why he did it, how he felt about it when he did it, and how he feels about coming clean now.”

Hill met Rose in 1986 at Pittsburgh s Three Rivers Stadium. He was in town with other Hollywood celebrities to participate in a softball game against a team of Pittsburgh Steelers football players before a Pirates-Reds baseball game. The pair was introduced by Pirates manager Jim Leyland, who was Hill s next door neighbor when he was growing up at 1020 Elm St. in Perrysburg.

Rose and Hill continued to cross paths in the years that followed, often at celebrity golf tournaments.

Around 1994, Rose moved to Los Angeles, where his daughter aspired to be an actress. A mutual friend gave Rose a copy of a screenplay Hill had written called The Longshot. It was the true story of Jim Eisenreich, a major leaguer who was diagnosed with Tourette s syndrome, a neurological disorder characterized by involuntary movements and vocalizations.

“He was intrigued by the story,” Hill said. “He said basically, How do you write a baseball story like you did, but you don t deal so much with baseball?

“At this stage, probably around 1998, Pete was going through a lot of conflict on how to deal with his situation, trying to get an audience with the commissioner [to consider lifting his banishment from baseball], that kind of thing.”

Rose agreed to let Hill write a book about him, though it took several meetings between the two before Rose finally opened up and confessed his misdeeds.

“[I told him] None of us can identify with 4,256 hits, Pete, because you re the only guy on the planet who got it. You ve got 17 major league records. I had a decent college career, but that s it.

I can t identify with playing pro ball for 24 years, but I can identify with pain. I can identify with hiding a lie. I can identify with obsessive behavior that wreaks havoc in your personal life.

If we can get to the key of that, we ll have a heck of a story. ”

My Prison Without Bars focuses not only on Rose s admission, but also on family history and brain chemistry. Citing experts, Hill argues that those factors help explain why the man known for his head-first slides dove head-first into baseball, sex and gambling.

“We took his mother s personality profile to the experts. She s what you call an oppositional defiant [disorder] personality,” Hill said. “This is a genetic personality type she was born with.” He said Rose also was born with it, and it means that he sees everything in life as a conflict.

Hill also profiled Rose s father, an obsessive compulsive workaholic perfectionist.

“Pete told me at one point while we were writing, Nobody ever tried to explain this stuff to me before. I said, Well, either they didn t know or a lot of people are intimidated by [you]. He s a very ornery, cantankerous guy, and I say that with a lot of respect.”

Not everyone respects Hill s explanations for Rose s problems.

“Hill never notes that ODD is a diagnosis applied mainly to children and adolescents,” wrote columnist Al Mascitti in The (Wilmington, Del.) News Journal. “Once such people are adults, they re just called jerks. ”

Responded Hill: “I would question anybody who would call anybody with an affliction a jerk. That s assuming they have the ability to control it without getting some help.”

Hill said Rose struggles with controlling urges because of a dopamine deficiency in his brain.

“In 1920 they didn t have that knowledge,” Hill said. “When [commissioner] Kenesaw Mountain Landis enacted that rule that you re banned for life [for gambling on baseball], he did so because it suited the times, it suited the era. Right now, we know better.”

Hill said that a habitual gambler is no different than an alcoholic or a drug addict. Each requires therapy, re-evaluation and - in Rose s case, he said - a second chance.

“The contrition is real, but I don t think he s ever going to be able to satisfy those cynics because Pete s too competitive and too prideful to let that side of him come through. Emotions and sensitivities are not part of his personality.”

Yet despite topping the New York Times non-fiction best seller list last month (it s currently No. 3), baseball s hit king hasn t made it to first base in the minds of many.

“There are critics,” Hill said. “There are those who don t like Pete Rose or have an axe to grind. They don t trust him. In some ways, Pete s like the boy who cried wolf, and he has to own up to that.”

Sports Illustrated ran excerpts from the book in its Jan.12 edition. In its Feb. 2 edition, five of the six letters to the editor were critical of Rose.

Columnists have taken swings too.

Jenkins, who was convicted in 1980 for cocaine possession while playing for the Texas Rangers, no longer supports his peer s entry into the Hall.

“I was very surprised with Ferguson Jenkins,” Hill said. “So was Pete, that someone who was given a second chance because of a drug conviction would actually criticize someone for gambling. That blew me away.”

Hill notes that seven of every 10 e-mails collected at peterose.com - Rose s Web site - have been positive. He said that some who attacked Rose, including media critics, have changed their stance after reading the 322-page book.

“I could have had every page dripping with remorse,” Hill said. “I could have had Pete weeping and crying and having this wonderful epiphany. You know what would have happened? People would have said, They re writing a propaganda piece to get Pete Rose into the Hall of Fame. ”

Hill said Rose knew he needed to acknowledge betting on baseball to be considered for the Hall of Fame, but added, “I don t think that s the only motivation. To say there was no self-serving interest in it, that s awfully idealistic isn t it? Everybody looks out for themselves. But that wasn t the sole motivation: Pete really wanted to come clean.

“Why now? I think it has worn on him. I don t think he s the same man at 62 as he was at 52. I don t think he has the same cravings. People have said, Can you trust Pete? ”

The author says you can, even if Rose hasn t always told the truth before.

“I feel very comfortable in the information Pete s given me. Let s be realistic - we worked together for 31/2 years. You get to know somebody pretty well.

“I think he genuinely feels remorse for what he did and I don t think he felt remorse 12 years ago.”

Hill also believes Rose s ban will be lifted and that baseball s hit leader will one day be enshrined in the Hall of Fame.

“Based on the medical evidence and the knowledge of who Pete is and why he did the things he did, it just seems too hypocritical to ban someone for life anymore, life without the possibility of parole.

“I don t believe Pete corrupted the game. I believe he corrupted himself. I believe he hurt himself far more, because the game has survived, the game has continued. Fans were hurt, people were disappointed, damage was done.

“But I believe Pete did more damage to himself than he did to anyone else.”