Whitner still the man of the house on defense

1/21/2012

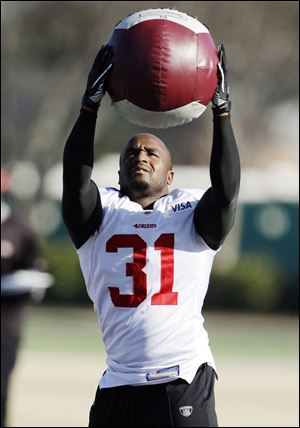

San Francisco 49ers strong safety Donte Whitner (31) participates in a drill during NFL football practice in Santa Clara, Calif..

SAN FRANCISCO -- San Francisco 49ers strong safety and Cleveland native Donte Whitner went from being told as a little boy that he would probably never walk again to being one step away from playing in the Super Bowl.

"It's tremendous to even be playing football at all," said Whitner, who will face the New York Giants in the NFC championship game on Sunday. "To be one victory away from being in the Super Bowl after everything I've been through is my biggest dream come true."

At 6 years old, Whitner was playing catch in his Kinsman Road driveway and the ball rolled into the street. He darted out after it and was struck by a car driving down the street. His mom, Deborah Robinson, got the call at work that her eldest son had been hit by a car, and she was convinced he was dead.

"Nobody would tell me anything but that he had been hit," she said. "All I could think of was that he was gone and they weren't telling me."

She raced home from her job at a nearby nursing home, blinded by her tears and screaming hysterically. "I could've been killed myself," she said. She was driven to Rainbow Babies & Children's Hospital, where Whitner had been taken by ambulance.

"I had to be strong in front of him," she said. "But the doctors told me he'd probably never walk again, and that he'd never, ever play sports again."

Whitner's legs had been shattered in 15 places, and he was placed in a full-body cast for six months. Robinson bought a little red wagon to cart him around and carried him up and down the stairs at home. After that, he was placed in a half-cast for another eight weeks and then had to learn how to walk all over again.

"He kept trying to tear those casts off his legs," she said.

Whitner vividly recalls being told by the doctors that he would probably never walk again.

"Even when you're 6, you understand what it means when somebody tells you you're not going to walk or play sports again," Whitner said. "It was the first time in my life where I actually had to believe in myself when nobody else did."

About four months after he took those first steps, he asked his mom to buy him a basketball hoop.

"I didn't want to do it," said Robinson. "I was so scared those little legs were going to pop. But I couldn't say no. He was so under the weather that he needed something. Sports was all he thought about."

Before long, Whitner was shooting hoops. By age 8, he wanted to play Pop Warner football, but knew his mom would never let him. He forged her signature and had his aunt help him get the physical.

"One day, his coach called me and said, 'Where's Donte? He's missed a few practices and we really need him!' " Robinson said. "I said, 'You must be talking about one of my nephews. Donte doesn't play football.'"

She searched the back porch and found Whitner's hidden uniform.

"He had stopped going be cause he thought I wouldn't approve," said Robinson, who keeps the forged registration form in a frame. "And he's right, I probably would've never let him play."

As time went on, word kept getting back to Robinson about how good her son was in football. "I went and watched and I could see what they were talking about, when I was able to keep my eyes open."

Whitner brought a certain ferocity to the football field, and they both knew where it came from.

"I grew up in a single-parent household, and I didn't really have a relationship with my father [Lindsey Robinson] growing up," he said. "He did so much time in prison for different reasons. I dealt with it on the football field. I always played like an angry man."

At home, it was a different story. Whitner was the man of the house from the time he was young. His mom raised not only him and his little brother, but also four and sometimes five of her nephews that her brothers and sisters left with her.

"Ever since I could walk, I was doing chores," said Whitner, who now has a good relationship with his father. "I cleaned, did the wash, wiped down walls, stairways, and toilets. I also cooked. My most famous thing was pork and beans. That and a big pitcher of Kool-Aid took care of everybody."

Because his mother worked two jobs, Whitner, second-oldest of the seven boys, got the kids up for school, and made sure they were all in the house at night.

"With the help of my grandma, my mom was able to make sure seven boys were fed, got good grades, had a home and went to church," said Whitner, now a father of three.

A near straight-A student, Whitner started out at Benedictine, but ended up at Glenville after his freshman year with coach Ted Ginn, Sr. There, he became close friends with current teammate Ted Ginn, Jr., and former 49er Troy Smith, and they all went to Ohio State together.

"Since the day I met Ted Ginn, Sr., everything's been going uphill for me," said Whitner. "He put us through rigorous workouts before and after school. He was like a father to me. The determination came from coach Ginn. It was all his vision from Day One."

Whitner won the national championship at Ohio State and then was a first-round draft pick -- eighth overall -- of the Bills in 2006, where he started at strong safety for five seasons. He signed with the 49ers last offseason and quickly became one of the team leaders. It was his crushing blow on New Orleans' Pierre Thomas on the opening drive last week that popped the ball loose and set the tone for the 49ers' victory.

What makes the playoffs even more special for Whitner is he's getting to share it with Ginn, Jr., who is like a brother to him. "We've dreamed of this for a long time," he said.

Whitner was so determined to get to this point, not even two shattered legs were enough to stop him.

"This shows you that with enough determination and belief in yourself, you can do any thing," he said.