Demolition requests pile up for homes in historic Vistula

10/23/2011

The Blade

Buy This Image

Richard Martinez chairman of the Vistula Historic District Commission, with vacant homes on Elm Street, and his home on North Superior Street, in Toledo, Thursday.

At a sparsely attended meeting of the Vistula Historic District Commission, longtime board member Mike Young couldn't hold back.

Three of the four items on Tuesday night's agenda were applications to demolish buildings in Toledo's oldest neighborhood, and he'd had it.

"I've been on this historic district commission for I don't know how many years, and we're still doing what we've always done," Mr. Young, a retired landscape architect, lamented. "We're still getting what we've always got, which is tearing down a bunch of houses."

The commission was established by the city of Toledo "to protect and enhance the historical and architectural characteristics of the Vistula Historic District." It reviews and decides proposals to make exterior changes to buildings in the district, yet between 2001 and 2010, the board also reluctantly approved 43 demolition applications.

The great majority were houses that had fallen victim to what neighborhood advocates refer to as demolition by neglect -- properties that are purposely neglected by the often-absentee owners so that demolition becomes a foregone conclusion.

Vistula, a neighborhood just north of downtown that dates to 1837, has been fighting the trend for decades -- fighting and losing.

Vacant, overgrown lots are interspersed amid 100-plus-year-old homes and townhouses -- some stately brick mansions, others boarded-up, falling-down frame houses. Windows are broken. Daylight streams through holes in roofs. An urban groundhog dashes across an alley and into its hole at the base of an abandoned duplex.

Richard Martinez, who is chairman of both the Vistula Historic District Commission and the Historic Vistula Foundation, is frustrated by the disrespect his North Toledo neighborhood has been shown for all too long, frustrated by the lack of enforcement of the city's housing code.

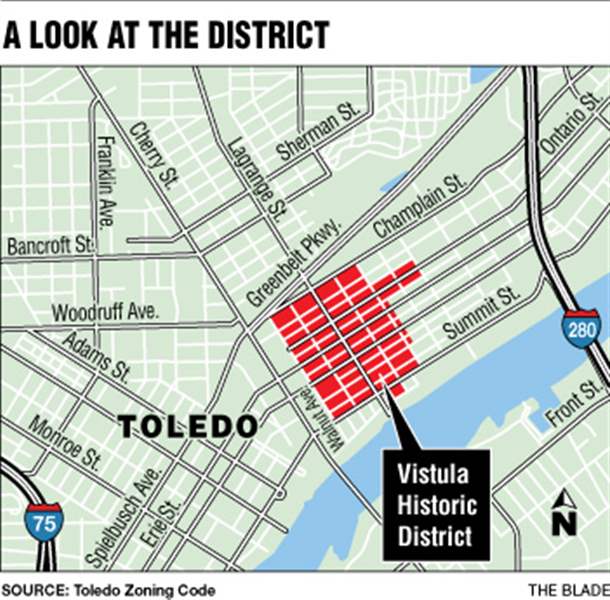

During a drive through the historic district, which is bounded by Walnut, Champlain, Chestnut, Magnolia and Summit streets, Mr. Martinez points to house after house that was occupied, was rehabilitated, and now has fallen into disrepair. He looks beyond the neglect to the intricate molding, the turrets, the fish-scale shingles, the quaint porches. He takes note of the success stories though they seem grossly outnumbered by the failures.

"Look at this," he said, pointing to a blue-and-white, two-story home with a minivan in the driveway. "This is a beautiful little 19th century home that's been taken care of. A family lives there. They're not rich, but they did a little painting. They did some repairs. Imagine this neighborhood if everyone took care of their home like this. It would be a delightful place to live."

The overwhelming lack of owner-occupied homes is precisely the reason Vistula has fallen into its state of disrepair, said Tom Gibbons, principal planner with the Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commission. Property owners, by and large, do not live in the historic district. A disproportionate number of houses and apartment buildings are rentals, many subsidized housing for the poor.

"It started in the '80s when developers got old buildings and rehabilitated them," Mr. Gibbons said. "At the time, it was great because it helped preserve them, but like anything, when you concentrate the poor in one area, you have a lot of problems."

Recently, the United North community development corporation put together a business plan with the Historic Vistula Foundation that proposes, in part, to work with the Lucas County Land Reutilization Corp. to acquire vacant properties in the historic district, properly mothball them to protect them from further deterioration and vandalism, and then market them to new owners for redevelopment and reuse.

Terry Glazer, United North's chief executive officer, said the land bank could be a key resource for curbing the demolition in Vistula, and he thinks it's worth the effort.

"I think this neighborhood has so much potential when you think of the fact that you not only have the historic district, you have the riverfront adjacent to that," he said. "What other neighborhood is like that? And it's adjacent to downtown Toledo. It's got everything going for it. It really does."

Linda Detrick-Jaegly, economic development and marketing director for United North, said a key part of the business plan for Vistula is to update the inventory of real estate in the district, assess each property, and prioritize structures that ought to be saved because of their architectural and historical significance. Lucas County Auditor records show the historic district has 577 parcels, although that figure includes vacant lots.

"It's almost a daunting project, but we have to do it," she said. "If we don't, we're going to lose that historic district."

She conceded that not every house can be saved, agreeing with fellow historic district commission member Toni Battle Gaines, who said at Tuesday's meeting, "I am a real champion for the historic district and historic homes, but realistically we can't save everything."

The commission, which ultimately approved demolition applications for two houses on Locust Street, is legally bound to OK razing structures if it finds the building has no features of architectural or historic significance or if there is "no reasonable economic return for the structure as it exists and there is no feasible alternative to demolition submitted to the applicant." Individuals or organizations that object to the demolition may appeal the commission's decision to the plan commission.

Mr. Gibbons said there's "no golden goose" that's going to solve the problem.

"How did the neighborhood get like that? Did it happen overnight? No. It was one building at a time, one block at a time," he said. "To undo that, you're going to have to do that again -- one building at a time, one block at a time."

Asked if he believed he would see the neighborhood turn around in his lifetime, Mr. Martinez, who moved into Vistula from South Toledo in 1988, thought for a moment before answering.

"We're always hopeful that it's going to change, but I don't think -- I don't know," he said. "That's why we're working with United North now."

Despite the high crime rate and the view of boarded-up homes and apartments just down the street from their brick Italianate home, Mr. Martinez said he and his partner, Judy Cattran, are there to stay.

"This house keeps us here. We love this house. It's a beautiful house," Mr. Martinez said. "And we have neighbors here that we know and we kind of stick together because of the fact that there are not that many of us around."

Contact Jennifer Feehan at: jfeehan@theblade.com or 419-724-6129.