Risk of neighborhood blight grows as banks delay sales of foreclosures

11/4/2012

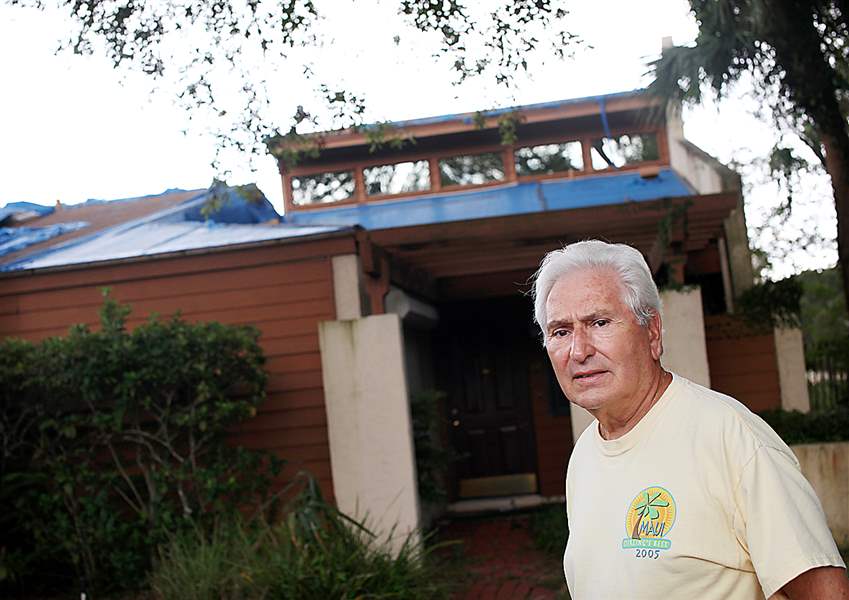

Richard Campanaro stands in front of an empty townshome in Cranes Roost Villas in Altamonte Springs, Fla. Mr. Campanaro says the home is a foreclosure that Bank of America has allowed to fall into disrepair. By slowly releasing their properties, some lenders can benefit from rising home values.

Orlando (Fla.) Sentinel

Richard Campanaro stands in front of an empty townshome in Cranes Roost Villas in Altamonte Springs, Fla. Mr. Campanaro says the home is a foreclosure that Bank of America has allowed to fall into disrepair. By slowly releasing their properties, some lenders can benefit from rising home values.

ORLANDO, Fla. -- A neighborhood’s chances of recovering quickly from the hung-over U.S. housing market depend not only on how many foreclosed homes it has but also, it seems, on which banks own the properties.

Bank of America, for instance, takes almost two months longer on average to sell a foreclosed property than smaller EverBank Financial does, according to new, nationwide data from the research company RealtyTrac Inc. And Bank of America, the lending giant that inherited many of its troubled mortgages when it bought Countrywide Financial in 2008, has been taking longer this year to sell its foreclosure properties than it took last year.

A lot of things can happen when long-abandoned houses sit on the market for additional months. By slowly releasing their foreclosed properties, for instance, some lenders have benefited from rising home prices this year.

But those long-held properties also rack up more unpaid association fees, overdue property taxes, repair costs, neighborhood complaints, and even code-enforcement fines as the months wear on.

At Cranes Roost Villas in Altamonte Springs, Fla., the first thing residents and visitors see as they enter the gated community is a leaky corner unit draped in blue tarp so long that the plastic sheeting has started to disintegrate.

“Bank of America put a bright-blue tarp on top of roof rather than repair it,” said longtime resident Richard Campanaro. “Half of it has blown off. It would make a wonderful haunted house if you wanted to do something for Halloween. It’s terrible — I wouldn’t even want to enter the property.”

Last year, it took Bank of America an average of 5.3 months to sell a foreclosure, according to RealtyTrac. So far this year, it has averaged 6.7 months. Deutsche Bank, Wells Fargo & Co., and Citigroup have also fallen further behind in selling their foreclosed properties. Through September, all of them were taking at least 20 percent longer than they took in 2011, based on RealtyTrac’s nationwide data.

Smaller banks appear to be more nimble when dealing with foreclosures, perhaps because they aren’t faced with nearly the same volume of properties, said Daren Blomquist, RealtyTrac vice president. And mortgage servicers with portfolios of higher-end properties are better able to sell those homes than are companies saddled with less-desirable houses.

But the longer a bank-owned house sits idle during the foreclosure process, the deeper it falls into disrepair.

“Banks are not typically too willing to repair these homes, particularly if there are property flippers ready, willing, and able to buy the more scratch-and-dent variety of homes and fix them up,” Mr. Blomquist said. According to RealtyTrac, the number of flippers is up 25 percent nationally compared with a year ago.

A group of nonprofit housing organizations recently filed complaints with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, accusing Bank of America of failing to maintain foreclosed houses in 13 cities’ minority communities. The groups included photos of houses with unlocked doors, mold, interior walls spray-painted with graffiti, and piles of trash heaped outside.

The Charlotte-based lending giant denied any wrongdoing and said it stands behind its property-maintenance and marketing practices.

Repeated safety violations at the same bank-owned houses have become such a recurrent theme for local governments that some of them, such as the city of Tampa, have considered establishing foreclosure registries, which require lenders pay $125 to register a property within 10 days of filing a foreclosure notice.

In registering a property, banks have to provide contact information for a property manager in case the house falls into disrepair and the local government — or the neighborhood’s community association — wants some action taken.

A spokesman for Wells Fargo said the company inspects foreclosures monthly, registers foreclosures as required, maintains abandoned houses, and secures them.