Influential monk topic of new film

12/6/2008

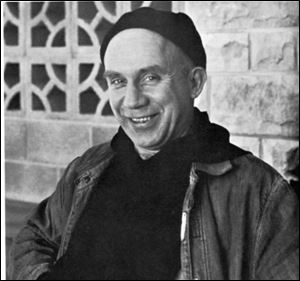

Thomas Merton, a Trappist monk who died Dec. 10, 1968 at age 53, wrote more than 60 books including the best-selling autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain.

Filmmaker and author Morgan Atkinson said he made a curious discovery while working on his new documentary, Soul Searching: The Journey of Thomas Merton.

There are a lot of Thomas Mertons out there, he said.

Merton was a Catholic monk and a poet, literary critic, philosopher, social justice activist, peacemaker, mystic, and spiritual director to many people searching for deeper answers.

Scholars and admirers have spent years studying just one of these slices of Merton s life, but Mr. Atkinson wanted his film to provide a broad look at the man and his legacy.

There was no way to try to tackle somebody as complex and whose life had so many different aspects to it as Merton s did in a one-hour documentary, Mr. Atkinson said in an interview this week from Louisville. I knew it would be ridiculous to try. So my hope was to interest people enough that they would go back on their own and read Merton s writings.

The documentary will debut on PBS stations nationwide Dec. 14, including local broadcasts at 10 p.m. that day on WBGU-TV (Channel 27) and at 10 p.m. Dec. 16 on WGTE-TV (Channel 30).

Mr. Atkinson wrote a companion book with the same title, published by Liturgical Press (206 pages, $19.95), that includes many additional insights from his two years of research that did not get into the film.

The documentary is being released shortly after the 40th anniversary of Merton s death at age 53 on Dec. 10, 1968, when he apparently was electrocuted after touching a fan during a visit to Bangkok.

Soul Searching includes interviews with more than 30 people including Merton scholars and his students and colleagues at the Abbey of Gethsemani in rural Kentucky, where Merton lived as a Trappist monk for 27 years.

He was considered a dangerous thinker by some of his fellow monks and superiors in the Catholic Church for taking an interest in, and writing about, such topics as Zen Buddhism and Eastern mysticism long before the general public in the United States were even aware of those practices, according to the Rev. John Dear in an on-camera interview.

But Merton obeyed orders when his abbot told him to stop writing about Zen Buddhism, Mr. Atkinson points out in Soul Searching.

Among the scholars interviewed was Lawrence Cunningham, professor of theology at the University of Notre Dame, who called Merton the greatest spiritual writer and spiritual master of the 20th century in English speaking America.

The only other spiritual writer whose influence compares in terms of enduring impact, according to Mr. Cunningham, is the perennially popular C.S. Lewis.

One of the reasons why Merton is so compelling a figure today is that he managed to write about very deep spiritual things, very deep convictions about the reality of God, without sounding particularly pious, Mr. Cunningham said.

Mr. Atkinson, 54, said he has been interested in Merton for more than 30 years and feels that the monk s writing has quite simply been a roadmap to living my life as a more fully human being.

For one thing, he said, Merton s whole life was a restless searching for a deeper expression of life.

Merton was born in Prades, France, on Jan. 31, 1915, and his family moved to Long Island, New York, that August to flee World War I.

His mother died when he was 10 and his father died five years later, leaving Merton with a family friend as guardian.

Merton lived a hedonistic lifestyle in college at Cambridge and then Columbia universities, nearly suffering a nervous breakdown, as some friends said, before converting to Catholicism and later becoming a monk.

Mr. Atkinson said Merton s wild living in his youth was consistent with his lifelong search for meaning. When his indulgences did not bring fulfillment, it led him to a spiritual quest.

In some ways he hit bottom in a spiritual sense [at Cambridge], Mr. Atkinson said. From that emptiness and sort of desolation he felt compelled to find deeper things in life than what he was doing.

Although Merton drank alcohol in excess and was involved with a number of women, his behavior was fairly innocent by today s standards, Mr. Atkinson said.

He had pretty high standards for himself and he saw how far he had fallen short of them. After really delving into one aspect of life the material aspect of it, the sensory aspect of it he felt there must be more to life than that.

Throughout his life, Merton was unflinchingly honest and not afraid to write about his struggles and his flaws. That is one reason why Mr. Atkinson and many other Merton fans are drawn to him.

I think it gives him a sense of authenticity. A lot of times there is some spiritual writing that I ll read and I ll feel like I m sort of being bs d or just getting a very pietistic approach that doesn t seem to have much connection with reality that makes sense to me, he said.

Merton had a gift for saying things about spiritual matters and pious matters in a way that was accessible to a normal person who is a spiritual seeker, Mr. Atkinson said.

Merton entered Gethsemani in 1941 and took his solemn vows in 1947. His autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, was published in 1948 and brought international attention to this cloistered monk.

John Eudes Bamberger, an abbot emeritus who studied under Merton, said despite first impressions, the worldwide reach of Merton s writings did not contradict his monastic seclusion.

Trappist monks lived at the time as though they had disappeared from the world, he said, and yet here s this 28-year-old monk writing his autobiography, as if he has a message for the whole world.

Abbot Bamberger said Merton began to feel that writing was a gift God gave him and that it was his way of responding to a hidden vocation.

The book became a best-seller, remains in print today, and led to a long-term publishing contract for Merton, who wrote 60 more books in his lifetime.

Mr. Atkinson said he wrestled with whether to write another book on Merton, since there are more than 100 already on the shelves. But he not only had 60 hours of taped interviews to draw from, he also something many early Merton biographers did not have access to: the monk s personal journals that were published 25 years after his death.

In those journals, you meet a very human person, he said. They really show his day-to-day life. He hasn t airbrushed the faults we all have. They show him sometimes being very petty. But they also show both the depths and the heights of his life. I think they were a real generous gift that was left to us.

David Yonke