BOTTOM LINE: STAY IN OPERATION

Ice-cream makers swallow costs as prices of raw materials spike

Loss of customers feared in bad economic times

8/9/2011

Jim Cappanari covers freshly made ice cream. He posted an apology for a recent 10-cent increase in the price of a cone.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

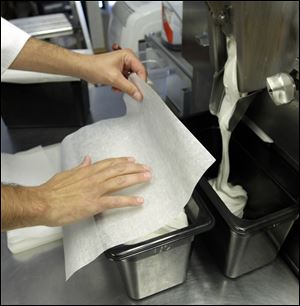

Jim Capannari, who runs a small ice-cream company in Mount Prospect, Ill., pours ingredients into a machine. He hasn't passed along much of the increases in costs of milk, butterfat, and sugar.

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- The cost of the milk, butter fat, and sugar that are key to Jim Capannari's ice cream have spiked this year, but he hasn't passed much of the cost along to customers.

The Illinois ice-cream maker and a lot of his colleagues don't feel that they can, saying customers will pay only so much in a down economy, even for high-end treats.

"The bottom line is, you want to stay in business," said Mr. Capannari, who went so far as to hang a sign in his suburban Chicago shop explaining why cones went up 10 cents.

There's no question the price increases for ice cream's raw materials have been steep -- milk prices have gone up an average 38 percent in the past year, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, while sugar prices are up almost 20 percent and the cost of high-fructose corn syrup rose just over 22 percent.

Yet the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics says the average price of a half gallon of ice cream has increased just 7 percent in that time.

The factors behind the price increases for ice cream's base ingredients are much the same as those for food in general -- global demand, a weak dollar that makes American products more affordable overseas, and the high cost of the mostly corn feed that most dairy cattle eat, according to Penn State University economist Jim Dunn, an expert on the dairy business.

In this case, he said, economic growth has turned the Chinese into major consumers of dairy products, but they don't trust their own country's powdered milk after tainted milk killed a number of babies and sickened thousands more. The relatively weak dollar makes American powdered milk a bargain in China and, as a result, the cost of a hundred pounds of milk -- a standard wholesale measure -- hit $22.10 last month.

"That is the highest price that we've ever seen," Mr. Dunn said.

Similarly, sugar prices have been increasing over several years of high demand and big producers such as Brazil coming up short.

"That was one of those things that I never knew I would have to get into -- commodities markets," joked Mr. Capannari, who said his start in the business a decade ago coincided with a roughly 400 percent increase in the cost of vanilla, something that caught him way off guard at the time.

Since then, he's gotten used to that sort of thing.

Jim Cappanari covers freshly made ice cream. He posted an apology for a recent 10-cent increase in the price of a cone.

High-end ice creams, however, have carved out a niche for themselves during the recession and now-stalled recovery, said Larry Finkel, the food and beverage research director for the market research company Packaged Facts in New York. The products represent a form of affordable luxury, a treat that stands in for more expensive indulgences, such as travel or electronic toys.

But even companies that charge a premium for their pints say they aren't making much money. Jeni's Splendid Ice Creams runs just shy of $10 a pint, but Chief Executive John Lowe said much of that goes toward the ingredients.

"We have worked hard not to raise prices and in the last year have not done so," Mr. Lowe said, explaining that Jeni's has tried to save money elsewhere, on transportation in particular.

"But the increase in commodities and fuel does impact the bottom line," he added. "We joke that we work in not a not-for-profit, but a low profit."