Rich history abounds in venerable city of Delhi

5/25/2014

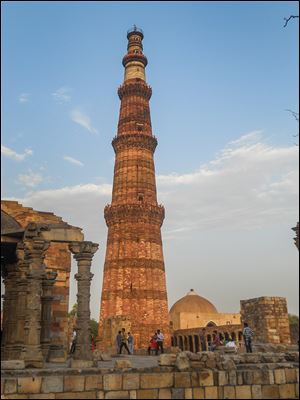

The 1,000-year-old Qutab Minar rises 237 feet above the surrounding ruins in Delhi.

S. AMJAD HUSSAIN

Dr. Hussain

DELHI, India — There are two Delhis. One is the old city, which the locals call Puraani Dilli, with its roots going back a millennium or two before the Common Era. The other is New Delhi, built in 1911 as the new capital of British India. It is, however, the old city with its narrow labyrinthine alleys, old homes, maddening traffic, the Red Fort, and the majestic mosque called Jama Masjid that is a magnet for people like me.

Calcutta (now Kolkata) had served as the capital of the East India Company and later, when sovereignty of India was transferred to the British government, as the capital of British India for 150 years. The shifting of the capital to Delhi, a thousand miles west of Calcutta, was a political move. There was, at the time, considerable political unrest in Bengal, and the British authorities did not want to have their capital in a vulnerable position.

In an interesting quirk of the British Raj, the capital would move at the approach of summer every year from Calcutta to the summer capital of Shimla in Himalaya, a thousand miles to the west. At the end of summer, the government would move back to Calcutta. The suffocating heat of the India plains was just too much for sahib log to bear. As a result the government was on wheels, bullock carts, and horse carts, and later trains and trucks, six months of the year.

Paratha, or deep-fried bread, is a specialty of the old city of Delhi. It has been sold at the same location for 142 years.

New Delhi is a modern city with wide leafy boulevards, stately buildings, and spacious bungalows with manicured lawns. But to understand the pivotal role Delhi has played in changing fortunes of empires and dynasties, one has to venture into the old city.

In its 3,500-year history, this city has been destroyed and rebuilt numerous times. Claudius Ptolemy (90-168 C.E.), the Roman-era astronomer, mathematician, and geographer, mentioned the city as Datedla. Delhi was prosperous and fabulously rich and was coveted by many a foreign invader.

Some, like Mahmud of Ghazni (10th century), who attacked India 17 times, came only to loot and pillage. Others stayed and became part of the land. Among the latter were the Khiljis (13th century), the Tughlaqs (14th century), and the Mughals (16th century). The British were the latest invaders who came as petty traders (early 17th century) but in due course became rulers and stayed for 350 years.

Some of the buildings and monuments still stand in silent testimony to those past rulers. Others have crumbled and can only be visualized through bits and pieces of artifacts and fragments uncovered by archaeologists.

One monument still standing is the 237-foot-tall Qutab Minar, constructed in 1192 by King Qutbuddin Aibak. Made of sandstone and marble and constructed in phases over 175 years, the tower is a marvel of engineering.

Nearby, virtually a stone’s throw away, is an iron pillar constructed about 1,600 years ago and dedicated to King Chandargupta, the founder of Maurya dynasty (320-185 B.C.E.). The 23-foot-high, rust-free pillar points to the amazing knowledge of metallurgical skills of the ancient craftsmen of India.

But perhaps the most-lasting imprint on the city was left by the Mughal emperors who ruled much of India from 1528 to 1757 C.E. Shah Jahan, the fifth Mughal ruler, had a knack for building lasting monuments. The Red Fort and Jama Masjid in old Delhi was built during his reign. He also built the Taj Mahal as a memorial to his wife Mumtaz Mahal.

Now, as then, the Red Fort and the large mosque called Jama Masjid define the geography of the old city. Running westward from the fort is a wide boulevard called Chandani Chowk that has been the heart of the commercial life of the city for hundreds of years. At one time, a canal flowed in the middle of the boulevard. On both sides of the road are old neighborhoods with the warrens of narrow serpentine alleys.

In one of these alleys lived in the 19th century Asadullah Khan Ghalib, a giant of Urdu poetry. He was the court poet to the last Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar, himself a poet of repute. Mr. Ghalib wrote both in Persian and Urdu, but his Urdu poetry, barely a slim volume, has overshadowed all his other work. His poetry has been set to music and has entered into the consciousness of the common man on the streets of India and Pakistan. Mr. Ghalib remains as relevant today as he was 200 years ago.

The 1,000-year-old Qutab Minar rises 237 feet above the surrounding ruins in Delhi.

My host and guide in the old city was Abdul Rehman, a lawyer and a lover of Urdu language and literature. Charming and engaging, Mr. Rehman was born and raised in the city and knows each and every nook and cranny. With him, I saw the old home of Mr. Ghalib, ate deep-fried bread (paratha) in one of the alleys famous for this delicacy, and visited Mr. Ghalib’s tomb just outside the city.

Mr. Ghalib was also the chronicler of the events that took place around the great mutiny of 1857, when there was a bloody uprising against British rule. In his letters written to friends, he describes the reign of terror that the British had wrought on the citizens of the city in the aftermath of the mutiny.

Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar was deposed and banished to Rangoon, Burma, to die in exile, and all of his progeny were put to the sword. While in Rangoon the emperor wrote an Urdu poem that captures the agony of exile:

O Zafar, how unfortunate have you become,

That you are denied even a tiny piece of land in your beloved country for burial.

This short couplet has entered into Urdu classics.

Delhi is also known as the city of saints and sinners. While it is difficult to point out sinners (except for the irrepressible writer, the late Khushwant Singh, who by his own account was a renegade sinner), there are plenty of saints buried in and around the city. The most famous among them is the 13th century Sufi saint Nizamuudin Aulia. His religious inclusiveness has left a deep imprint on India, where the pilgrims to his shrine just outside Delhi include Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, and Christians.

During my stay in Delhi I was invited by the Urdu department of Delhi University to read from one of my Urdu books. I was most grateful for this rare opportunity. Surrounded by the large size photographs and paintings of Urdu literary luminaries of the past three centuries peering down at the podium was a bit intimidating but also very uplifting and satisfying.

Since I was reading my own work, I did not think the giants of yesteryear would break out of their frames as in Washington Irving’s essay The Art of Book-Making.

Dr. S. Amjad Hussain is a retired Toledo surgeon.

Contact him at: aghaji@bex.net