State doesn't keep the right graduates

10/1/2006

Last in a series

CLEVELAND - The human heart sparks electricity with each beat. When it skips and its rhythm breaks, life turns fragile.

It took Charu Ramanathan, Ping Jia, and their graduate adviser in a Cleveland lab to map the heart to show what trips its electrical circuits. They knew their work belonged in hospitals, so they patented it.

A business was born.

Ms. Ramanathan came to Case Western Reserve University a decade ago to pursue a doctorate in biomedical engineering, which no college in her native India offered. Ms. Jia left China for the same reason.

The world sends many of its best minds to Ohio universities each year, where they perform ground-breaking research. That research spawns patents, which are one of the best predictors of a state's wealth and lead to new companies - the kind of firms that the leading candidates for governor call vital to the state's economic future.

But Democrat Ted Strickland and Republican Ken Blackwell rarely discuss the researchers behind those breakthroughs.

Instead, the candidates talk a lot about "brain drain," the flight of homegrown college graduates from the Buckeye State.

Maybe they should go back to school.

In fact, Ohio keeps more of its college graduates than the average state, a recent study of 1.11 million alumni records found. But the state bleeds the scholars who should be the heart of a high-tech economy: people holding doctorates in biology, chemistry, and engineering.

At a time when Ohio's economy needs more and better ideas, the state isn't losing young minds, it's losing the most educated young minds.

Ted Strickland interrupted a busy day of fund-raising on Aug. 31 to address a small crowd of reporters at the University of Toledo. Flanked by students and shaded by the stone tower of University Hall, the southeast Ohio congressman attacked rising tuition costs and what he called a critical problem facing the state. "Ohio leads the nation in young people leaving the state and going elsewhere," Mr. Strickland declared. He promised to reverse the trend by creating "decent-paying jobs."

Ken Blackwell doesn't often agree with Mr. Strickland. But at a shopping-mall rally in Perrysburg the next day, Ohio's secretary of state nearly echoed his opponent. "Right now, too many of our young people believe that the only way that they can go up is to go out," Mr. Blackwell said, adding: "There's no more important job for the next governor of this state than putting an Ohio option back into the hands of our young people."

University of Toledo research suggests both candidates for governor are misguided.

UT's Urban Affairs Center analyzed 1.11 million alumni records of Ohio graduates between 1980 and 2003. It found more than 80 percent of those who graduated between 2000 and 2003 did not leave for "cool cities" along the coast. They stayed in Ohio. Out of the entire 24-year pool of alumni, 70 percent are still Buckeyes.

Between 66 percent and 70 percent of college graduates nationwide continue living in their home state, according to an ongoing survey by the U.S. Department of Education.

"If you can keep someone for three years after they graduate," said Patrick McGuire, the UT sociology professor who authored the study, "you almost always have them for life."

The study detected another trend, which the Ohio Board of Regents confirms. Those with master's degrees, doctorates, and professional degrees are 50 percent more likely to leave Ohio than those with bachelor's degrees.

The average salary for people with doctorates is $73,892 a year, compared with $48,724 for bachelor's degree holders, according to the Census Bureau. That income gap is $6,000 wider than the one between college graduates and high school graduates.

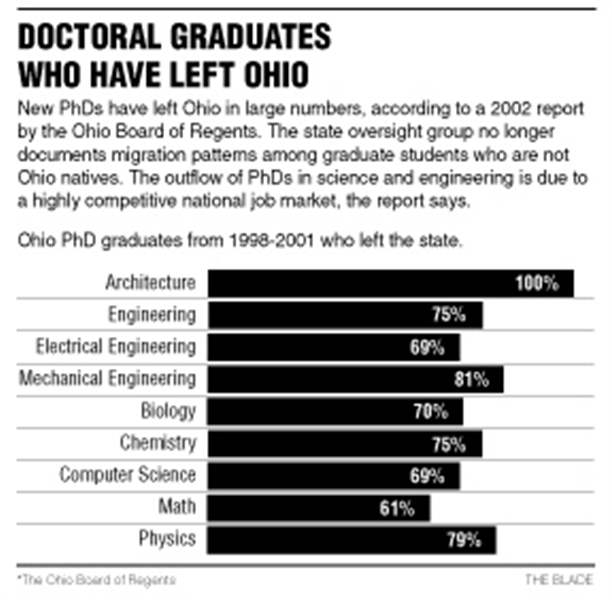

A 2002 performance report issued by the Ohio Regents found 70 percent of those holding doctorates in biology, chemistry, and engineering leave Ohio. Graduate degree recipients have job opportunities nationwide, unlike most of Ohio's bachelor's degree holders, later performance reports noted.

The Regents can't give more recent statistics because they stopped measuring overall graduate student migration three years ago.

Of native-born U.S. citizens with doctorates in science and engineering, about 41 percent remain in the state where they attended graduate school, according to the National Science Foundation.

Advanced degrees stoke inventive economies. A 1999 study published in the journal Science found that PhDs educated in America, but born elsewhere, were more likely to perform ground-breaking research, file patents, and start new companies.

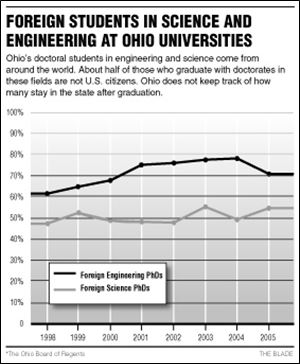

More than half of the graduate students in biology, chemistry, and engineering at Ohio's universities come from abroad. The presence of foreign students pumped $405 million into the state's economy in 2004, according to NAFSA: Association of International Educators.

Soundararajan Srinivasan had never seen America firsthand when he left India to study biomedical engineering in Ohio State University's doctoral program.

After six months on campus, Mr. Srinivasan chose the topic of his dissertation: how to filter out white noise and focus your hearing on what is important. His work helped him land a job at the Bosch Group in Pittsburgh, an automotive technology firm.

"I interviewed at a couple places in California, Switzerland, GM in Michigan," Mr. Srinivasan said. "Coming out of a grad school with a PhD, you have avenues."

Mr. Srinivasan likes Pittsburgh. He would have preferred to stay in Columbus. But no Ohio business interviewed him.

A 2003 analysis of census data by the Governor's Commission on Higher Education and the Economy concluded that Ohio's real obstacle was its inability to attract college graduates from other states. Salaries were higher elsewhere. College graduates who left Ohio made about $3,000 more a year than those who stayed or moved into the state.

And as top graduate students leave, Ohio universities face increasing pressure from politicians to jump-start an economy that isn't keeping up with the nation.

"A knowledge-based economy requires cooperation between the higher education and business communities," Mr. Blackwell says in his education platform. Mr. Strickland calls investment in university research and innovation "the ultimate answer" to the question of how to create better Ohio jobs.

The pressure comes as Ohio ranks 40th in the country in funding higher education on a student-by-student basis, the Regents note.

In 2004, a state commission proposed to improve Ohio's economy in part by spinning off companies from university research. The idea came late to Ohio, where until 2000 ethics laws prohibited public university professors from licensing their discoveries to businesses.

Ohio universities have improved dramatically in patent revenue since, but they face stiff competition. Michigan State University alone generated $36 million from licensed patents in 2004. That's $10 million more than all of Ohio's nonprofit research institutions combined. And only 24 percent of the patents Ohio's universities license go to in-state companies.

At Case Western, Ms. Ramanathan and Ms. Jia developed software that images a heart in three dimensions. As a result, doctors can treat abnormal heart rhythms with targeted operations, rather than controlling the symptoms through more general therapies, such as medication, implanting devices, or surgery.

The research initiated by their adviser, Yoram Rudy, led to the financing in August of CardioInsight. Ms. Ramanathan and Ms. Jia co-founded the company, which is about to start clinical trials.

Both women have young children. In her spare time, Ms. Jia browses Chinese Web sites because "when you come to Case, the lab is your whole world." She estimates that 90 percent of her classmates left Ohio after graduation.

"That has been my complaint to my husband, that my good friends left," Ms. Jia said.

As a technology transfer executive at Case Western, Joseph Jankowski helped shepherd the work Ms. Ramanathan and Ms. Jia performed in the lab into CardioInsight.

"Grad students and post-docs are the primary researchers and investigators," Mr. Jankowski said. "There's probably not a technology we license that doesn't have input from a graduate student."

No Ohio institution receives more from patents than the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. The clinic's 15,000-square-foot business incubator features a pair of mass spectrometers, which measure the mass and concentration of atomic particles - work too technical for most "tinkerers" with bachelor's degrees.

"By and large," said Chris Coburn, executive director of the clinic's innovation division, "what we're doing is not going to be done in a garage."

Patents allow universities to translate their research into economic opportunity. But interim Regents Chancellor Garry Walters noted that students must be a college's primary focus because "the best form of technology transfer is a highly trained graduate."

Some of Ohio's top companies say they can't get the graduates they need from Ohio.

Akron-based Goodyear rode a truckload of new products to renewed profitability in recent years, thanks to a research revolution borrowed from nuclear weapons.

Goodyear previously designed a new tire, built it, tested it, and repeated the process three or four times before it was satisfied, which could take up to three years.

In the 1990s, the Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico - which devise delivery systems for nuclear warheads - showed the company how to cut the time in half by using computer modeling to test tires before they hit the road.

Goodyear struggles to recruit enough engineers to fill its research staff of 1,000, said Joseph Gingo, the company's executive vice president for quality systems and chief technical officer.

Ohio's "rust belt" identity makes it harder to land out-of-state engineers to work the computer testing models, Mr. Gingo said, and in-state schools aren't producing enough engineers on their own.

"The education system in Ohio has to be able to supply us with engineers who can apply these tools," Mr. Gingo said. "This is the way you're going to have to educate your students in the future. It's not just my industry, it's every industry."

Mr. Gingo has no problem recruiting the kinds of engineers who create the testing models, instead of the ones manipulating them. "The kind of guys that like [computer] modeling," he said, "if they lived in California and you gave them a great modeling challenge, they will move from San Diego to Akron."

Some of Ohio's most innovative thinkers agree that nothing will attract bright minds to Ohio better than opportunity. It's the conundrum at the heart of the state's economic struggles: Will great thinkers create great jobs, or will great jobs lure great thinkers?

Mr. Coburn says the Cleveland Clinic's reputation helped it land top researchers from Japan, Croatia, and Argentina.

"You might have to work harder," he said, "particularly in February when it's sleeting, but we get our people."

Ms. Ramanathan and Ms. Jia could have followed their adviser to St. Louis but chose to start CardioInsight near Case Western. "The high-tech sector," Ms. Ramanathan said, "especially in the university, the collaborations, made me forget that it is Cleveland."

A job drew a young World War II veteran named David Morgenthaler to the Great Lakes. He stayed and in 1968 founded a pioneering venture capital firm in Cleveland, where, at 87 years old, he still manages a $2.5 billion portfolio.

Mark Schweitzer was a West Coast lifer when he spurned a New York offer to take a research position at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. He came for the job but stayed for the lifestyle.

"My family actually likes it here," Mr. Schweitzer said. "We like our neighborhood and we like our schools. It turns out that's very important."

Mr. Schweitzer and a colleague, Paul Bauer, recently wrestled 75 years of data into a comprehensive analysis of what affects state economies the most.

It was their study that found a dearth of ideas, measured by patents and education, behind Ohio's economic woes.

The economists currently are studying detailed patent data to figure out what really breeds brain power in cities and states. They don't expect to finish anytime soon.

In the meantime, Ms. Ramanathan has a theory based on personal experience. Clearing Ohio's obstacles to innovation, she said, takes persistence.

"You bang on a door," she said, "and keep at it, keep at it, keep at it, until the door falls off."

Contact Joshua Boak at: jboak@theblade.com or 419-724-6728.