A house full of dreams

2/12/2005

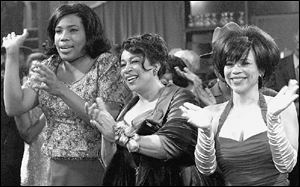

Pauline (Macy Gray), Nanny Crosby (S. Epatha Merkerson), and Bertha (Rosie Perez) enjoy a night out at Maxie s, a local nightclub in HBO s presentation of Lackawanna Blues.

Pauline (Macy Gray), Nanny Crosby (S. Epatha Merkerson), and Bertha (Rosie Perez) enjoy a night out at Maxie s, a local nightclub in HBO s presentation of Lackawanna Blues.

Ruben Santiago-Hudson grew up in the 1950s and '60s in an all-black rooming house in the small upstate New York city of Lackawanna. Even as a child, he realized how special his surroundings were and how different were the people he encountered at 32 Wasson Ave.

Years later, he would tell the story of that rooming house in what would become an acclaimed one-man off-Broadway show called Lackawanna Blues.

Now, with financing from HBO Films, he has fleshed out his tale and adapted it for film. The result is a lively, colorful, and nostalgic look at the type of black community-within-a-community that flourished in America during the dark days of segregation.

The movie, which premiered last month to rave reviews at the Sundance Film Festival, gets its cable TV premiere at 8 tonight on HBO.

Lackawanna Blues is the story of Rachel ("Nanny") Crosby (Law and Order's S. Epatha Merkerson in the role of a lifetime), owner of a boarding house that also serves as a diner, community center, and halfway house for a collection of drifters, grifters, and others who are not quite able to make it on their own. It's also the place where everyone in the neighborhood goes each week to drink, gamble, dance to the jukebox, and enjoy Nanny's Friday night fish fry.

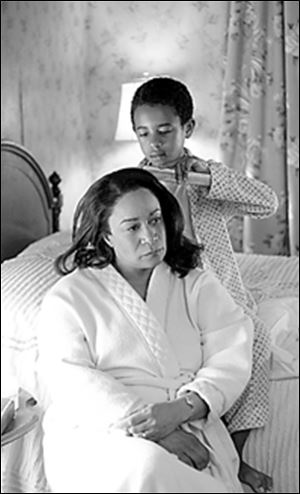

The story is told mostly in a series of flashbacks recalled by the adult Ruben, who is taken in by Nanny at age 2 when his parents (Jimmy Smits and Carmen Ejogo) aren't able to raise him. While lavishing her love and tenderness on "Junior," as she calls the young Ruben, Nanny also makes time for a succession of needy tenants, providing a helping hand, a sympathetic ear, or a shoulder to cry on.

And there are plenty of needy souls: a one-legged former psychiatric patient (Louis Gossett, Jr.); the squeaky-voiced Pauline (singer Macy Gray), who keeps a straight razor in her bra and wields it against her two-timing boyfriend; a recluse (Jeffrey Wright) who's a black history buff and a double murderer; and a hulking guy (Delroy Lindo) who lost an arm, he says, while "defending a lady's honor."

Young Ruben (Marcus Carl Franklin) tends to Nanny (S. Epatha Merkerson).

At a time when blacks are not well-served by a predominantly white society, Nanny functions as a one-woman Department of Social Services, dispensing assistance when it's needed, with no red tape involved. Or, as an adult Ruben recalls her, "Nanny was like the government, if it really worked."

There's a surprising number of well-respected actors in the cast - other big names include Ernie Hudson, Rosie Perez, Liev Schreiber, and Patricia Wettig - even though many of them have very minor roles. That could be a testament to the movie's subject matter, and maybe to the clout of its producers, one of whom is Oscar-winning actress Halle Berry.

As the film's title implies, music is a big part of the fabric of this community. As one of the characters explains the blues to Junior, "This is our story - we don't need no history books." Hip-hop artist Mos Def brings a manic energy to his role as a bandleader at Maxie's, the local nightclub, and Robert Bradley is a fiery blind soul singer whose wrenching songs echo the stories being told in the movie.

Nanny is a soft-hearted woman, but she can be tough, too. When her ne'er-do-well husband Bill (Terrance Howard) drives off and leaves Junior behind during a fishing trip, she is quietly seething when Bill gets home.

"If you ever mistreat this child again, man, I will blow the back of your head off," she says, and Bill knows she means it.

In another scene, she faces down a wife-beating husband who comes to the boarding house looking for his woman - despite the fact that the man is half her age and twice her size.

While the movie is a tribute by Santiago-Hudson to Nanny, it's also a fond look back at the type of community in which people used to really take care of each other.

Its director, George C. Wolfe, whose Broadway credits include Angels in America and Bring in Da Noise, Bring in Da Funk, calls Lackawanna Blues a "love poem to segregation," which underscores a certain irony - that for all its evils and injustices, racial segregation in the United States did have its flip side, namely the resulting creation of close-knit communities like this.

Of course, to some that's painting a distorted picture, one that's a little too warm and fuzzy, akin to saying that slavery wasn't all bad because it enabled blacks to get together and sing spirituals in the cotton fields.

As the years passed, integration provided more opportunity for blacks, in Lackawanna as elsewhere in the country. But for every door that integration opened, it meant the closing of a door in Lackawanna's African-American enclave.

There's no neatly packaged conclusion to Santiago-Hudson's story. As the adult Ruben leaves Nanny's house, he takes a long look around the old neighborhood. Where there had once been vibrancy and life, there are now abandoned buildings, boarded up and decaying.

To all outward appearances, the community he once knew and loved is dead. But inside the rooming house, Nanny - now an elderly woman with health problems of her own - still presides over what's left of her local constituency.

When somebody tells her she should take care of herself now instead of continuing to worry about everybody else first, she waves them off.

"I'm all right," she says. "This is what I do."

Contact Mike Kelly at: mkelly@theblade.com

or 419-724-6131.