Chilling look at Everest: PBS documentary tells story of killer storm

5/13/2008

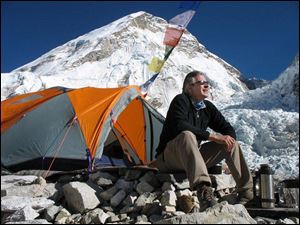

Climber and filmmaker David Breashears outside his tent at Everest Base Camp. He made it back to safety.

For generations, Mount Everest has represented the biggest natural high on Earth, both literally and figuratively. The world's highest peak, it towers more than 29,000 feet - that's nearly 5 1/2 miles high - and has attracted countless adventurers who dream of looking down from a craggy perch on the rooftop of the world.

Since the early 1950s, when Sir Edmund Hillary became the first man to have officially reached the summit, nearly 3,000 climbers have made it to the top. More than 200 others have died in the attempt.

A dramatic new PBS documentary called Storm Over Everest tells the story of five of those deaths that took place on the south side of the mountain during a ferocious storm in May of 1996. The two-hour film, which will be shown at 9 tonight on WBGU-TV, Channel 27, and WGTE-TV, Channel 30, was made by world-renowned climber and filmmaker David Breashears, who was leading an IMAX film team on Everest at the time of the storm but made it to safety before the worst of it hit.

The deaths caused by the storm are well known, and have been the subject of several books and at least one movie, Into Thin Air. Many of the accounts of the tragedy have stirred up controversy, in part because they've assigned blame to various guides and other members of the three climbing parties that became stranded on the mountain.

Breashears' movie makes no attempt to play the blame game. Instead, he deftly combines interviews with survivors, breathtaking footage he shot over the two days when the tragedy took place, plus additional scenes he shot during a subsequent visit to Everest. He also stages dramatic re-enactments of portions of the story, seamlessly blending everything to produce a coherent and evenhanded account.

Viewers are left to reach their own conclusions about what, if anything, might have been done to avert the tragedy.

Two factors are undeniable. First, because there were nearly three dozen climbers on Everest that May day, bottlenecks resulted in some areas along a well-traveled "highway" to the summit, and many people remained at or near the top too long. But that might not have mattered as much had it not been for the second factor, the sudden appearance of a freak storm.

Caused by a cyclone in the nearby Bay of Bengal, the monster storm came boiling up from below, trapping the climbers high up on the mountain's south face. "Within the space of five minutes, it changed from really a good day with a little bit of wind to desperate conditions, something I'd never experienced the ferocity of before," says survivor John Taske.

With the storm worsening, many in the climbing parties began a frantic descent toward the relative safety of high camp, while guides remained high on the mountain to assist other climbers. As darkness began to fall, swirling, hurricane-strength winds reached 80 mph, and the temperature plunged to minus-30.

Climbers became disoriented in the blizzard, blinded by blowing snow and ice pellets, and many were unable to find their camp. Those who made it to the wind-lashed tents huddled inside, wrestling with the life-or-death decision of whether to go back out and try to rescue those who were still lost in the whiteout.

In the end, some managed to make it back to camp on their own, while others were saved by climbers who ventured back out to lead them to safety. Still others never made it back.

Knowing what can happen during an Everest expedition, one has to wonder what makes people take such risks just for the chance to stand atop a mountain, even if it's the biggest one on the planet. Is it ego, or maybe something else?

The gorgeous vistas captured by Breashears' cameras give part of the reason, and comments from some of the survivors provide other clues. Beck Weathers, who barely survived the climb - he lost most of both hands, his nose, and parts of both feet to frostbite - explains in an extraordinarily personal interview that extreme mountaineering has always provided the only relief he's found in a lifetime of depression.

"I John Wayne'd it, so I never let anybody know about [the depression]," he says, "and I discovered that if you drove your body hard, when you did that you couldn't think. And that lack of thinking, as you punished your body and drove yourself, was amazingly pleasant."

Sandy Hill, another survivor, expresses similar sentiments. "Other people when their life is at a difficult spot, [they] turn to drugs or drink or credit cards," she says. "I go to the mountains. That's always worked for me."

There will always be questions about whether more of the climbers could have made it safely down the mountain if different decisions had been made, but no one can answer those questions with any certainty - not even those who were there.

Weathers, who was twice left for dead during the ordeal, is philosophical about the actions of his fellow climbers.

"Everybody always says that the definition of character is what you do when nobody is looking," he says. "When we were up there, we didn't think anybody was looking Some individuals come out of that, I think, justly proud of their actions. Others would probably not want anybody to know."