Granddaddy of tech is 100 years old

6/16/2011

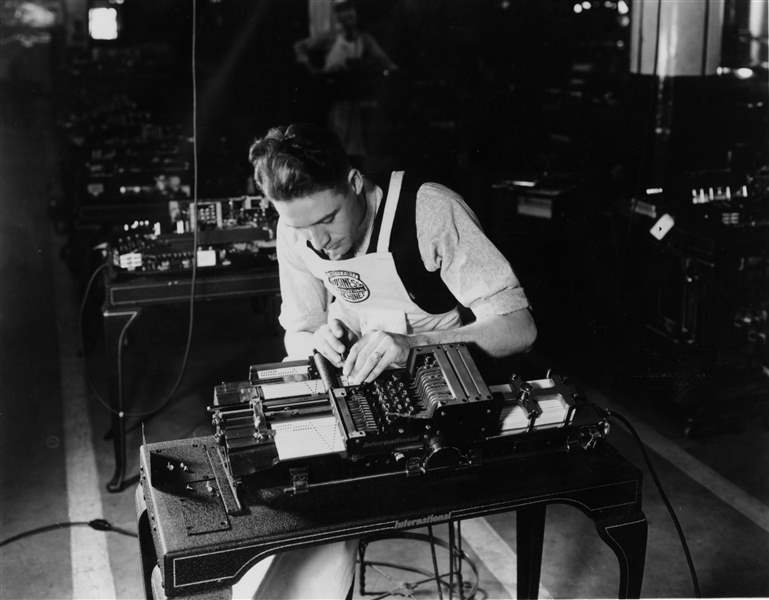

Punch-card-machine assembly was a function of the companies that joined on June 16, 1911, to form what was later renamed IBM.

IBM CORP.

Punch-card-machine assembly was a function of the companies that joined on June 16, 1911, to form what was later renamed IBM.

ENDICOTT, N.Y. -- Google Inc., Apple Inc., and Facebook Inc. get all the attention. But the forgettable everyday tasks of technology -- saving a file on a laptop, swiping an ATM card to get cash, scanning a gallon of milk at a market checkout line -- that's all IBM Corp.

International Business Machines turns 100 Thursday without much fanfare. But its much younger competitors owe a lot to Big Blue.

After all, where would Groupon.com be without the supermarket bar code? Or Google without the mainframe computer?

"They were kind of like a cornerstone of that whole enterprise that has become the heart of the computer industry in the U.S.," says Bob Djurdjevic, a former IBM employee and president of Annex Research.

IBM dates to June 16, 1911, when three companies that made scales, punch-clocks for workers, and other machines merged to form the Computing Tabulating Recording Co. The modern-day name followed in 1924.

With a plant in Endicott, N.Y., the business also made cheese slicers and machines that read data stored on punch cards. By the 1930s, IBM's cards were keeping track of 26 million Americans for the newly launched Social Security program.

Those machines might seem quaint in the iPod era, but they had design elements similar to modern computers. They had places for data storage, math processing areas, and output, said David Mindell, professor of the history of technology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Punch cards carted from station to station represented what business today might call data flow.

The force behind IBM's early growth was Thomas J. Watson, Sr., a demanding boss with exacting standards for everything from office wear (white shirts, ties) to creativity (his slogan: "Think").

Mr. Watson, and later his son, Thomas, Jr., guided IBM into the computer age. Its machines were used to calculate everything from banking transactions to space shots.

As the company swelled after World War II, it threw its considerable resources at research to maintain its dominance in the market for mainframes, the hulking computers that power whole offices.

By the late 1960s, IBM was consistently the only high-tech company in the Fortune 500's top 10. IBM famously spent $5 billion during the decade to develop a family of computers designed so growing businesses could easily upgrade.

It introduced the magnetic hard drive in 1956 and the floppy disk in 1971. In the 1960s, IBM developed the first bar code, paving the way for automated supermarket checkouts. IBM introduced a high-speed processing system that allowed ATM transactions. It created magnetic-strip technology for credit cards.

The company now known as Big Blue developed the bar code and created magnetic-strip technology for credit cards. But a blunder on personal computers nearly cost the company its existence.

For much of the 20th century, IBM was the model of a dominant, paternalistic corporation. It was among the first to give workers paid holidays and life insurance. It ran country clubs for employees generations before Google offered subsidized massages and free meals.

"The model really was you joined IBM and you built your career for life there," said David Finegold, dean of the School of Management and Labor Relations at Rutgers University. Transfers to other cities were still common enough that employees joked IBM really stood for "I've Been Moved."

The origins of the company's nickname, Big Blue, are something of a mystery. It may simply derive from IBM's global size and the color of its insignia.

IBM's gold-plated reputation was based in part on ubiquity and reliability, as well as a relentless sales force. But its fortunes began to change as bureaucracy stifled innovation.

The company had slipped with the rise of cheap microprocessors and rapid changes in the industry. In an infamous blunder, IBM introduced its influential personal computer in 1981, but it passed on buying the rights to the software that ran it -- made by a start-up called Microsoft.

IBM helped make the PC a mainstream product, but it quickly found itself outmatched in a market it helped create. It relied on Intel for chips and Microsoft for software, leaving it vulnerable when the PC industry took off and rivals began using the same technology.

The PC's casing wasn't as important as the technology inside it, and IBM didn't own the intellectual property inside its own machines. In addition, the rise of smaller computers that performed some of the same functions as mainframes threw IBM's main moneymaking business into disarray.

With its legacy and very survival at stake, the company was forced to embark on a wrenching restructuring.

In the 1990s, the firm slashed prices and eliminated jobs. IBM, which had peaked at 406,000 employees in 1985, shed more than 150,000 in the 1990s as the company lost nearly $16 billion over five years.

With around $100 billion in annual revenue today, IBM is ranked 18th in the Fortune 500. It's three times the size of Google and almost twice as big as Apple. Its market capitalization of around $200 billion beats Google and allowed IBM last month to briefly surpass its old nemesis, Microsoft.

Although transformed, IBM remains a pioneer, the envy of the technology industry. Hewlett-Packard Co.'s new chief executive, Leo Apotheker, said one of his primary goals is to strengthen the company's software and services businesses to compete better with IBM.