Entrepreneurs tear into products so you can repair them yourself

1/7/2013

Co-founders of iFixit Kyle Wiens CEO, left, and Luke Soules CXO, right, look at the replacement parts of electronic devices.

MCT

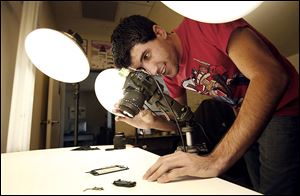

Andrew Goldberg, technical writer at iFixit, photographs a teardown of a iphone at their San Luis Obispo, California office where the company illustrates how to repair your electronics yourself through online photographs and videos.

SAN LUIS OBISPO, Calif. — Jake Devincenzi was thrilled to get his hands on Google’s new Nexus 4 smartphone. He admired its sleek black case and large touch screen — and he couldn’t wait to tear it apart.

In a small room cluttered with discarded computer parts, Mr. Devincenzi picked up a blue plastic stylus and eased the tool into a seam on the side of the phone as three co-workers watched.

Minutes later, a pop. The tear-down had begun.

“We’re in,” he said, and grinned.

Each time Mr. Devincenzi plucked a part from the Nexus 4, he took a high-resolution photo and posted it online. By the end of the week, more than 60,000 people had scrutinized the tear-down, curious to know what was inside.

Mr. Devincenzi, a 20-year-old student at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo, works part-time for IFixit, a company that has less of a business mission than a manifesto: “Repair is independence. We have the right to remove ‘Do Not Remove’ stickers.”

With the helping hands of technicians such as Mr. Devincenzi and repair guides written by volunteer tech experts, IFixit is tapping into growing frustration with cellphones, tablets, and computers that, once broken, are almost impossible to fix. The company says it wants to teach people how to repair electronic devices once again — and will sell them the tools to do it.

The company’s logo is a clenched fist thrusting a wrench in the air.

“It’s not like it was 10 years ago, when you could open things up and kind of half-recognize what was in there,” said Sean Campbell, a technology industry analyst with the Oregon research firm Cascade Insights. “I think most people have given up.”

To IFixit staff, every high-resolution photograph of naked phone bits splayed across a table is a small act of rebellion against big technology companies like Apple, Google, and Samsung. Tear-downs, they say, are a rallying cry for the common man to grab a screwdriver and take back the right to do it yourself.

“We’re not necessarily actively anti-Apple or anti-‘the Man,’ ” said Scott Dingle, 25, a customer service representative. “It’s more like, we train other people to do it themselves.”

What is now a staff of 35 began as two people. In 2003, Cal Poly freshmen Kyle Wiens and Luke Soules started selling laptop parts out of a dorm room. When they couldn’t find manufacturer-issued repair guides, they wrote their own. The first manual they posted online got 10,000 page views in the first weekend.

Co-founders of iFixit Kyle Wiens CEO, left, and Luke Soules CXO, right, look at the replacement parts of electronic devices.

They moved their business to a three-car garage, then a house, then a loft-like two-story office in downtown San Luis Obispo. Most IFixit employees are younger than 35. Many grew up taking apart toasters and other household appliances.

Last year, IFixit earned $5.9 million in revenue by selling parts, kits, and tools. Some of its more popular items include a “spudger” to adjust small wires, a five-sided screwdriver that fits Apple’s proprietary screws, and a magnetic mat to keep track of tiny pieces that come loose.

Some of its tools resemble teeth-cleaning instruments. That’s because the first tools IFixit used had been discarded by a dentist.

After Christmas, the company usually sees a spike in sales of parts, Mr. Wiens said. He attributes that to people who decide to repair their old gadgets if they don’t get a new one as a gift.

Mr. Soules, 28, is the business mind. He runs the in-house shipping center and handles the money. The revenue he oversees covers operating costs, including salaries, tear-downs, and expensive trips to buy gadgets the moment they come out.

Mr. Wiens, 28, is the chief executive and the ideas guy. In college, he dreamed of building a robot that would pick strawberries. Today he dreams of a world where computers don’t wind up in landfills, but are fixed instead.

IFixit is not the only Web site that offers repair manuals, but its tear-downs are special because they expose a company’s proprietary technology, said Scott Swigart, an analyst at Cascade Insights.

The Nexus 4 tear-down revealed a new chip for high-speed data connection. The discovery became news, because Google had not previously disclosed that the phone would have the chip.

Seeing a logic board lying exposed on a table goes a long way toward shattering any aura of mysticism surrounding a new device, said David Aghassi, a freshman at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland who uses IFixit guides and repair kits to fix laptops at the campus repair shop. He checks tear-downs multiple times a day to see how they progress.

Tear-downs are so important to IFixit’s DNA that the staff will do almost anything to be the first to open a device — even fly halfway around the world.

Getting the Nexus was much easier. UPS inadvertently delivered the phone to IFixit a day before it officially went on sale.

Often, IFixit employees trawl the Internet for consumers who may have gotten a gadget ahead of the scheduled launch, or fly to different countries to buy devices that aren’t yet on sale in the United States.

Before the iPad Mini went on the market Nov. 2, Mr. Soules and tech writer Andrew Goldberg flew to New Zealand with heat guns and photo equipment. New Zealand is 21 hours ahead of Pacific time. They planned to have a tear-down posted on the Web before the iPad Mini went on sale in the United States.

But 14 hours before the product’s launch in New Zealand, IFixit’s chief information architect, Miroslav Djuric, found two iPad Minis for sale in Berkeley, Calif. He had scooped his own co-workers. The tear-down staffers left behind in San Luis Obispo went into work just before midnight on Halloween, ready for an all-nighter fueled by doughnuts and coffee.

“Missing Halloween as a college kid to tear apart something that no one’s ever seen before?” said Mr. Devincenzi, who works part time while attending school. “I guess I don’t mind.”

IFixit rates each device for ease of repair. The Nexus 4 got a seven. Mr. Devincenzi and coworker Brittany McCrigler knocked off points for glue. Adhesive makes devices thinner, but it makes opening them very difficult.

That’s especially true for Apple products, which are notoriously hard to open and fix. Making any changes to Apple hardware can void the warranty, and the Genius Bar support that comes with it. Newer iPhones are protected by custom-designed screws. The iPad is held together almost exclusively with glue. To open it, IFixit has traditionally used a heat gun, suction cups, and guitar picks. Some shattered remnants of iPads, evidence of failed attempts, lie around the office.

Removing the screen became slightly more user-friendly when Ms. McCrigler suggested a technique she’d adapted from massage therapy training: Fill a bag with rice, stick it in the microwave, and lay it across the screen’s edge to melt the glue. They call it the iOpener.

Persuading non-techies to tinker is one of the company’s biggest hurdles. Repairs can go wrong, and do — even for the professionals. Screens shatter. Wires snap.

“But once people have their first fix, they’re hooked,” IFixit sales manager Eric Essen said. “When I fixed my iPhone and it turned on, I was like, ‘I am a god! I am Frankenstein!’ ”