Add veterans' voices to Mauldin's record of WWII

11/7/2010

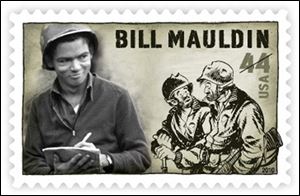

Bill Mauldin was honored by the U.S. Postal Service this year.

It isn't often that a four-star general's order is trumped by an enlisted man's popularity, but even George Patton answered to a higher authority - a guy with five stars named Dwight Eisenhower.

The enlisted man? Tech Sgt. Bill Mauldin. Mr. Mauldin, who died in 2003, was the Army grunt whose cartoons that portrayed the poignant and often ugly realities of World War II endeared him to his fellow soldiers.

In the process, however, some higher-ups were not amused. General Patton issued an order that Sergeant Mauldin had to tone down his criticism of officers in his cartoons.

Perhaps General Patton had been offended by a Mauldin cartoon that showed a general arriving by car at a camp near the front lines. A cook peers out of the mess tent: "Another dang mouth to feed," he says.

Or maybe it was the cartoon of two officers looking down from a mountain ridge, admiring the scenery but apparently oblivious to the graveyard below. "Beautiful view," says one. "Is there one for the enlisted men?"

More than half of Mauldin's 600 wartime cartoons were sketched in combat. Most appeared in Stars and Stripes and other newspapers back home in the states, much to the chagrin of General Patton, who vowed at one point to "throw his ass in jail."

But if General Patton was upset by Mauldin's work, his boss was not. His order died a quick death when General Eisenhower, supreme commander of the Allied Forces in World War II, found out about it. Mindful of the morale boost the cartoons provided the enlisted men on the front lines, Ike countermanded the order and said Sergeant Mauldin could draw whatever he wanted to.

This year, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp honoring Mauldin. It features a photo of the young sergeant with his drawing pad, which was taken in Italy on Dec. 31, 1943. He is just 21 years old but looks much younger. He appears to be glancing to his left at a drawing of his two favorite characters, his fictional buddies Willie and Joe.

Fictional? Maybe, but Sergeant Mauldin was the foot soldier's champion, and there was a bit of Joe and Willie in every American soldier in the fight.

Recalling Mauldin's work in 2010 is relevant on its own merit, but there's another reason to remember what he meant to the guys in the foxholes.

Sixty-five years after the war ended and seven years after Mauldin's death, the sad reality is that we are losing our World War II veterans at an accelerating rate - 1,100 of them a day. Of the 16 million Americans who served in the military in World War II, fewer than 2 million are still alive.

With most of those in their 80s and 90s, nearly all will be gone by 2020, just 10 years from now, according to Martin Morgan, historian for the World War II Museum in New Orleans.

As the ranks of our WWII vets dwindle, the museum is one of several organizations striving to preserve the personal accounts of their experiences in Europe or the Pacific. The Library of Congress and the U.S. Latino and Latina WWII Oral History Project are involved in similar projects.

Those are commendable efforts, but one suspects that these recordings will be archived somewhere and seldom heard by anyone but scholars.

If you have a surviving World War II veteran in your family, or know a friend who served, here's a suggestion. Record his or her living history before it's too late. Burn it on a compact disc and share it with others in the family.

It's not uncommon for aging vets to feel some reluctance to share the details of their service. War is an ugly thing. Nearly 300,000 Americans died in battle in World War II. Almost 700,000 were wounded. They were all heroes. The stories of those who came home remind us that they were among the very best of our "greatest generation."

Thursday is Veterans Day. By the time your Thursday edition of The Blade arrives, we will have lost another 3,000 of them. Take the time. Make the effort.

I guarantee your vet will know all about Bill Mauldin. Along with war correspondent Ernie Pyle, Mauldin crafted a living record of a tragic but ultimately triumphant chapter in American and world history.

Television brought the horrors of Vietnam to the evening news. But it was Tech Sgt. Bill Mauldin, a generation earlier, who showed the tragedy of war through the most ironic medium imaginable: cartoons.

Thomas Walton is retired editor and vice president of The Blade. His column appears every other Monday.

Contact him at: twalton@theblade.com