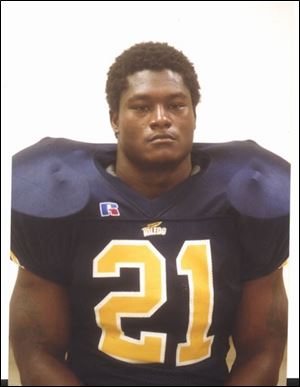

Rocket battles sickle cell anemia

11/2/2000

William Bratton was diagnosed with the sometimes painful disease at age 8.

It was one play in a game of many big plays, but it was perhaps the most satisfying moment of the night for the University of Toledo football team.

Junior tailback William Bratton burst 37 yards around right end late in the third quarter against Central Michigan on Sept. 30. It was the Rockets' second-longest run from scrimmage and their third-longest offensive play this season, and it led to a field goal in a 41-0 victory at the Glass Bowl.

For Bratton, it was a form of validation. He was UT's second-leading rusher last season, but has been slowed this year by assorted injuries and recurring bouts with sickle cell anemia. His is No.3 on the depth chart behind starter Chester Taylor and Antwon McCray.

Against Central Michigan, Bratton displayed glimpses of what made him a highly desirable recruit who rushed for 1,862 yards and carried Lima Senior High School to the 1996 state championship game.

Those precious moments sustain Bratton against the physical pain that has become a regular part of his life.

“When I do things like that, it shows me I can compete and play football. I don't know anyone else that plays (football) with sickle cell. I feel blessed,” said Bratton, 22. “I've learned to stay out there and compete; don't quit. When it's your turn to play, go out there and get it done.”

Bratton was diagnosed at age 8 with sickle thalassemia, an inherited, chronic blood disease in which the red blood cells become crescent-shaped instead of circular and function abnormally. The unusual shape can make it difficult for blood to flow to many parts of the body, and can cause tissue damage and damage to most organs, including the spleen, kidneys and liver. It is also accompanied by severe pain.

The disease occurs primarily in people of African heritage, with approximately one out of 400 African-Americans affected.

In some cases patients are afflicted with permanent anemia, making simple physical tasks difficult and participation in athletic competition nearly impossible.

In Bratton's case, his sickle cell count is normally low enough to allow him to play football.

“William is a courageous young man. Without a doubt, he has overcome an awful lot,” Toledo coach Gary Pinkel said. “He never complains. He keeps fighting through it.

“So many people said William would never play college football because of sickle cell. He has proved all of them wrong.”

Said Bratton: “When I'm sick, it's hard to describe the pain. Morphine doesn't help. It starts in my back and goes to my joints, my elbows and my knees. When it gets really bad, it hurts all over.”

Two years ago Bratton suffered a sickle cell crisis in his dormitory room. He needed two teammates to take him to the hospital.

Upon leaving the hospital, the 220-pound Bratton was 10 pounds lighter and considerably weaker. He is usually among the Rockets' strongest players with the ability to bench-press 370 pounds, but could barely lift 200 pounds after that episode.

Even when healthy, Bratton tires quickly. Most players can remain on the field during a lengthy drive; Bratton can do four or five consecutive plays before having to come out for a rest. On those occasions when he has stayed on the field for 10 or 11 straight plays, “I was so tired I couldn't even drink water.”

This year Bratton was felled by four sickle cell episodes, three before August two-a-day practices and another about two weeks before the Sept. 2 opener at Penn State.

“That really set me back,” Bratton said. “Even though you're tired you try to keep going because you don't want to let your teammates down.”

“As far as I can tell, he handles it very well,” said Rocket defensive end DeJuan Goulde, who himself collapsed and was taken to the hospital in an ambulance following a bronchial attack late in a game against Syracuse last season. “I'm not sure what it does to him, but if it's worse than what I see he hides it well. Because he makes it seem like it's really no big threat to him.”

Bratton, after missing the opener, has carried the ball in six of the Rockets' next seven games despite suffering a thigh contusion and a mild stress fracture in his foot. He is fourth on the team in rushing with 95 yards on 24 carries and has one touchdown.

Last year Bratton was second on the team with 486 rushing yards and four rushing touchdowns.

“He's missed a lot of time but I think we're in the process of getting him back. He started doing a little better a week ago,” Pinkel said. “When we get him back we'll start playing him more.”

For Bratton, every day is a challenge. He knows the average life expectancy for African-Americans with the disease is in the mid-40s, but he refuses to dwell on the future.

“They told me the life expectancy is not that long for a person with sickle cell. I don't really pay attention to that,” Bratton said. “As far as playing sports and keeping up with everybody else, that is really hard for a person with sickle cell. If you can do that, you're accomplishing something.”