MARGARET THATCHER, 1925-2013

British ‘Iron Lady’ dies, but her legacy endures

1st female P.M. ruled for 11 years

4/9/2013

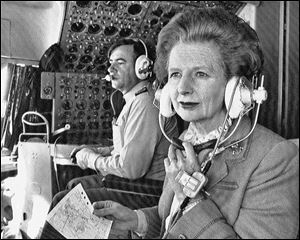

British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher sits in the cockpit during a flight to Hong Kong from Beijing on Dec. 20, 1984.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher sits in the cockpit during a flight to Hong Kong from Beijing on Dec. 20, 1984.

LONDON — Margaret Thatcher, the “Iron Lady” of British politics who set her country on a conservative economic course, led it to victory in the Falklands war, and helped guide the United States and the Soviet Union through the Cold War’s difficult last years, died Monday of a stroke. She was 87.

She had been in poor health for months and had dementia.

British Prime Minister David Cameron cut short a trip to return to Britain after receiving the news, and Queen Elizabeth II authorized a ceremonial funeral with military honors — a notch below a state funeral — at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London.

“The world has lost one of the great champions of freedom and liberty, and America has lost a true friend,” said a statement issued by the White House.

Ms. Thatcher was the first woman to become prime minister of Britain and the first to lead a major Western power in modern times.

Hard-driving and hardheaded, she led her Conservative Party to three straight election wins and held office for 11 years — May, 1979, to November, 1990 — longer than any other British politician in the 20th century.

The tough economic medicine Ms. Thatcher administered to a country sickened by inflation, budget deficits, and industrial unrest brought her wide swings in popularity, culminating with a revolt among her own Cabinet ministers in her final year and her shout of “No! No! No!” in the House of Commons to any further integration with Europe.

But by the time she left office, the principles known as Thatcherism — the belief that economic freedom and individual liberty are interdependent, that personal responsibility and hard work are the only ways to national prosperity, and that the free-market democracies must stand firm against aggression — had won many disciples.

At home, Ms. Thatcher’s political successes were decisive.

She broke the power of the labor unions and forced the Labor Party to abandon its commitment to nationalized industry, redefine the role of the welfare state, and accept the importance of the free market.

Abroad she won new esteem for a country that had been in decline since its costly victory in World War II.

But during her first years in power, even many Tories feared that her election might prove a terrible mistake.

Former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher pauses at the casket of former U.S. President Ronald Reagan as he lies in state in the Capitol Rotunda on June 9, 2004.

In October, 1980, 17 months into her first term, Ms. Thatcher faced disaster.

More businesses were failing and more people were out of work than at any time since the Great Depression. Racial and class tensions smoldered. Even her close advisers worried that her push to stanch inflation, sell off nationalized industry, and deregulate the economy was devastating the poor, undermining the middle class, and courting chaos.

At the Conservative Party conference that month, the moderates grumbled that they were being led by a free-market ideologue oblivious to life on the street.

With electoral defeat staring them in the face, Cabinet members warned, now was surely a time for compromise.

To Ms. Thatcher, they could not be more wrong.

“I am not a consensus politician,” she said. “I am a conviction politician.”

Her tough stance did the trick.

A party revolt was thwarted, the Tories hunkered down, and Ms. Thatcher went on to achieve great victories. She turned the Conservatives, long associated with the status quo, into the party of reform.

Her policies revitalized British business, spurred industrial growth, and swelled the middle class.

But her third term was riddled with setbacks.

By the time she was ousted in another Tory revolt — this time over her resistance to expanding Britain’s role in a European Union — the economy was in a recession and her reputation tarnished.

To her enemies she was a woman who railed against the evils of poverty but who was callous and unsympathetic to the plight of the have-nots.

Her hostility toward the Soviet Union and her persistent call to modernize Britain’s nuclear forces fed fears of nuclear war and even worried moderates in her own party.

It also caught the Kremlin’s attention. After a hard-line speech in 1976, the Soviet news media gave her a sobriquet of which she was proud: the Iron Lady.

Yet when she saw an opening, she proved willing to bend.

She was one of the first Western leaders to recognize that the Soviets would soon be led by a member of a new generation, Mikhail Gorbachev, and invited him to Britain in December, 1984, three months before he came to power.

“I like Mr. Gorbachev,” she declared. “We can do business together.”

Her rapport with the new Soviet leader and her friendship with President Ronald Reagan made her a vital link between the White House and the Kremlin in their tense negotiations to halt the arms race of the 1980s.

Margaret Hilda Roberts was born on Oct. 13, 1925, in Grantham, Lincolnshire, 100 miles north of London.

Her family lived in a cold-water flat above a grocery store owned by her father, Alfred, the son of a shoemaker.

Alfred Roberts was also a Methodist preacher and local politician, and he and his wife, Beatrice, reared Margaret and her older sister, Muriel, to follow the tenets of Methodism: personal responsibility, hard work, and traditional moral values.

Margaret learned politics at her father’s knee, joining him as he campaigned as a candidate for alderman and borough councilman as an independent.

“Politics was in my bloodstream,” she said.