Climate talks stalled over finance, carbon cuts

11/23/2013

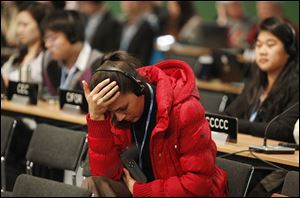

Delegates attend the closing session of the 19th conference of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in Warsaw, Poland today.

WARSAW, Poland — The inability of more than 190 countries to agree on climate aid to developing countries and milestones for work on a new global warming pact has pushed U.N. climate talks into an extra day.

After all-night talks, a new draft agreement emerged today with vague guidelines on when countries should present their carbon emissions targets for a larger deal that’s supposed to be adopted in Paris in 2015.

Developing countries want to make sure that richer countries adopt stricter targets than they do and have resisted a push by the European Union and the U.S. for a clear timeline.

The latest draft said countries should present their commitment by the first quarter of 2015 if “in a position to do so.”

Negotiations were expected to continue into this afternoon.

“Climate negotiations are understandably tense because there is still a perception that if one country wins the other loses,” said Jake Schmidt of the Natural Resources Defense Council. “That isn’t true as countries clearly have a huge domestic upside to action, but that perception still lingers.”

The U.N. climate talks were launched in 1992 after scientists warned that humans were warming the planet by pumping CO2 and other heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere, primarily through the burning of fossil fuels.

In Warsaw, negotiators were trying to lay the foundation of a deal in 2015 that would take effect five years later, but were bogged down by recurring disputes over who needs to do what, when and how.

Countries made progress on advancing a program to reduce deforestation in developing countries, an important source of emissions because trees absorb carbon dioxide.

Climate financing proved harder to agree on. Rich countries have promised to help developing nations make their economies greener and to adapt to rising sea levels, desertification and other climate impacts.

They have provided billions of dollars in climate financing in recent years, but have resisted calls to put down firm commitments on how they’re going to fulfill a pledge to scale up annual contributions to $100 billion by 2020.

“There is absolutely nothing to write home about at the moment,” Fiji delegate Sai Navoti said, speaking on behalf of developing countries.

Pointing to the devastating impact of Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines, island nations also demanded a new “loss and damage mechanism” to help them deal with weather disasters made worse by climate change. Rich countries were seeking a compromise that would not make them liable for damage caused by extreme weather events.