WITHOUT WARNING: Effects and reform of the WARN Act

Flaws, loopholes deny employees protection mandated by WARN Act

7/16/2007

First of four parts

Robert Phason and others at Meridian Rail in Illinois received eight-days notice that the plant, in background, was closing

WASHINGTON -- A federal law that requires companies to give notice to workers losing their jobs is so full of loopholes and flaws that employers repeatedly skirt it with little or no penalty, a Blade investigation has found.

Worker advocates say the law -- which requires many employers to notify their employees 60 days before they close a plant or lay off dozens of employees -- is in desperate need of reform because workers all over the nation have suffered.

On Dec. 31, 2003, Robert Phason and his co-workers at the Meridian Rail plant in Chicago Heights, Ill., received a letter telling them that the factory was closing in eight days because the company's assets were being sold.

The new owners didn't rehire Mr. Phason, a 34-year employee, and 36 others.

"My wife was doing dialysis and I had no insurance. I had to scrape up money to get coverage so she could keep going to dialysis. That was more devastating to me than anything else, such as missing meals," he said. Mr. Phason was unemployed for several months before he found a part-time job as a janitor.

READ MORE: Effects and reform of the WARN Act

Five years after losing their jobs at a western Pennsylvania call center, Richard Buterbaugh and his wife, Rebecca, are still recovering financially.

The Buterbaughs remember vividly when managers told them and 129 others that they weren't needed any more. They were told to leave immediately.

"You don't have a job and it's sudden and it's unexpected," Mr. Buterbaugh said. "It was like, 'OK, now what are we going to do? We have no income.'"

Since 1988, when Congress passed the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act - known as the WARN Act - employers have laid off tens of thousands of workers nationwide with little or no notice, The Blade found.

The inadequacy of the law has fueled the frustration of employees such as Mr. Phason and Mr. Buterbaugh, who face steep odds in holding their former employers accountable.

In crafting the WARN Act, Congress did not provide for enforcement of the law, forcing workers to sue former employers that don't provide the required notice.

Making a case

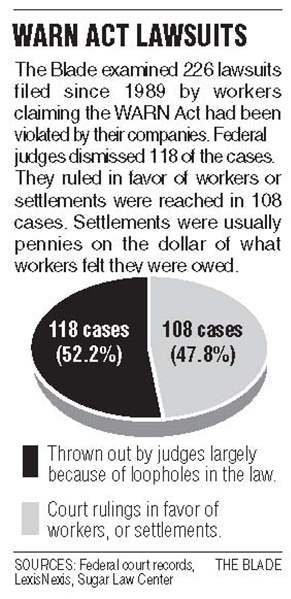

A Blade analysis of 226 lawsuits filed in federal courts across the country since 1989 revealed that judges threw out more than half of the cases.

In the majority of those decisions, judges cited loopholes in the law, ranging from companies that said they tried their best to give notice to employees to firms that claimed they couldn't predict bad financial times.

In 108 cases, WARN Act lawsuits resulted in settlements or with the courts siding with the displaced workers. But in dozens of those cases, workers received only pennies on the dollar of what they felt they were owed.

The law requires companies to pay employees up to 60-days pay when they fail to provide proper notice.

In November, 2004, U.S. District Judge James Carr in Toledo begrudgingly approved a settlement that paid $375 each to employees of National Machinery Co. who lost their jobs when the Tiffin factory closed without notice in late 2001.

Several of the workers, who had claims for more than $4,000, devoted most of their working lives to National Machinery and were never recalled when the plant reopened under a new name a few months later.

In court, Judge Carr labeled the settlement a "pittance" but told the angry workers it was the best they could expect under the weak federal law.

Calls for reform

Lawyers and worker advocates say there are hundreds of instances each year when workers have been laid off with little or no notice, but attorneys declined to pursue lawsuits because of loopholes in the law and difficulty in collecting a judgment.

The three leading Democratic presidential candidates reacted to The Blade's investigation by calling for reform of the WARN Act.

U.S. Sen. Hillary Clinton of New York said if elected president, her administration would pursue efforts to update the law to "reflect the realities of the modern economy."

"The Blade's findings highlight that the legislation is not achieving its goals, and that the legislation needs to be updated and improved to better serve the needs of U.S. workers," she said in a statement.

Former U.S. Sen. John Edwards of North Carolina said: "Families' hold on the middle class is more precarious than ever - the chances that an average person will experience a 50 percent or larger drop in income has more than doubled since the 1970s."

"We need to strengthen the WARN Act, including its enforcement, so it provides working Americans with the fair notice Congress intended when jobs are downsized or outsourced," Mr. Edwards said in a statement.

U.S. Sen. Barack Obama of Illinois said when factories shut down, it's the government's job to "step up on behalf of the unemployed."

"We must give the WARN Act teeth, to ensure that workers are not left in the lurch without a job or a paycheck," Mr. Obama said in a statement.

The leading Republican candidates for President did not respond to requests for comment.

U.S. Sen. Sherrod Brown (D., Ohio) said he plans to pursue an overhaul of the WARN Act.

"We should reconsider this law that has not served the public the way an overwhelming number of House members and senators thought it would," Mr. Brown said.

Companies operating in the United States are covered by the WARN Act if they have 100 or more full-time workers at one location. The law requires employers to provide notice 60 days before a plant closes if 50 or more employees lose their jobs.

The activists who pushed in the 1980s for passage of the WARN Act said the law has provided a cushion to tens of thousands of workers when companies comply with the statute.

But they indicated that when firms exploit problems in the law, they intensify the alienation of workers who feel abandoned by their employers and their government.

Pro-business groups and corporate attorneys acknowledge that some companies game the WARN Act by finding ways to cut workers without violating the law.

"We have seen companies out there that lay off 45 people a quarter; they just keep clicking away at it until they get to that 500-employee figure that they want to get to over a year and a half," said Mark Wilbur, president and chief executive officer of Employers Group, a Los Angeles-based personnel consulting firm.

"Some people call it a loophole. The reality is it's the way the law is written. If you don't like the law, write your legislator," Mr. Wilbur added.

The time has arrived for Congress to close loopholes and put more "teeth" into the WARN Act, said Julie Hurwitz, former executive director of the Sugar Law Center for Economic and Social Justice - a nonprofit law center based in Detroit that has focused for 16 years on enforcement of the WARN Act.

"There is a lot of anger out there," she said.

Meridian Rail

On Dec. 31, 2003, management at the Meridian Rail plant in Chicago Heights, Ill., sent its 149 workers a letter: The factory was closing and their last day of work would be Jan. 7, 2004.

"Mad as hell" is how Clifford Rush described his reaction.

He had worked since 1973 at the plant, which made rail products including switches and freight railcar wheels.

Two weeks before sending employees the letter, the owners of Meridian had a handshake deal to sell the company's assets to an Alabama-based corporation, VAE Nortrak.

The sale to Nortrak took place on Jan. 8, 2004.

Nortrak didn't rehire 37 workers, including Mr. Rush and other officers of the United Steelworkers of America Local 7234, when the plant reopened.

Mr. Rush, who couldn't find a job for two years, learned the Department of Labor had no enforcement power over the WARN Act.

He and other workers sued Meridian in 2005. A federal judge last year sided with the company, but in March an appeals court overturned the decision. The former Meridian employees continue to wait for the money they say they are owed.

Mr. Rush said the Department of Labor should enforce the WARN Act.

"I pay taxes. The government should work for me. The Department of Labor should have the authority to say, 'Hey, you violated the law,' and impose fines on companies. I feel that will stop these companies from doing this," he said.

"I gave my whole life to that company. It was not the first time we had been sold, but it was the first time we had been treated that way - to get a slap in the face," Mr. Rush added.

Melissa Goyette, and about 1,200 of her co-workers lost their jobs with Mortgage Lenders earlier this year. She now works in a lower-paying job with Bond Financial Services in Longmeadow, Mass.

Mortgage Lenders

With major changes in the U.S. economy over the last two decades, sudden plant closings and major layoffs have spread from blue-collar workers to white-collar workers.

Melissa Goyette quickly moved up the ranks at Mortgage Lenders Network, a rapidly growing mortgage lending company based in Middletown, Conn.

But faster than her own corporate rise, the 24-year-old Ms. Goyette lost her high-paying job in early January.

A week before her layoff, Ms. Goyette said management told employees in her division that their jobs were safe despite chatter about problems with the lending markets because of slowing home sales and increasing foreclosures.

"They weren't very honest with the staff of the company about what was going to be happening in the upcoming weeks," said Ms. Goyette, who worked for Mortgage Lenders Network for nearly two years. In 2006, she said she made $70,000 as a senior production coordinator.

On Jan. 23, after Mortgage Lenders Network had terminated hundreds of its employees, management belatedly filed a WARN Act notice with the Connecticut Department of Labor.

Last month, two former Mortgage Lenders Network employees filed a lawsuit against the company's owners on behalf of its 1,200 laid-off employees, asserting that the lender violated the WARN Act. The case is pending.

Some notice, Ms. Goyette said, would have given employees time to look for new jobs and get their finances in order.

Instead, Ms. Goyette and many of her colleagues were forced to settle for lesser jobs to continue earning paychecks. Ms. Goyette said she has taken a big pay cut in her new job as a financial administrator with Bond Financial Services in Longmeadow, Mass.

As former Mortgage Lenders Network employees struggle to return to solid financial footing, Mitchell Heffernan, the company's president, continues to enjoy a luxurious lifestyle, despite the fact that his business is in the midst of bankruptcy proceedings.

Mortgage Lenders currently operates out of an office building, in Rocky Hill, Conn.

Mr. Heffernan owns a $2.73 million, 7,828-square-foot colonial home in the exclusive Hamburg section of Lyme, Conn., according to the city assessor. He also owns a nearby horse barn on nearly 11 acres of land, valued at $881,000, and six vehicles, including an Aston Martin, a Range Rover, and a Cadillac Escalade.

Connecticut Attorney General Richard Blumenthal, in an April news release, said he intended to criminally prosecute Mr. Heffernan for failing to pay 61 employees up to $2.5 million in wages.

Mr. Heffernan's attorney, Robert Scandone, last week declined to comment.

Comm Comm

When a company abruptly closes a plant or lays off a large number of employees, the burden of proof is on the workers to show the WARN Act was violated.

It is a difficult task, and even if former employees succeed, collecting the money owed to them is another huge hurdle - as Richard and Rebecca Buterbaugh and 129 of their former co-workers learned.

On May 8, 2002, their employer - Communications & Commerce LLC, a help-desk call center in Indiana, Pa., known as Comm Comm - closed abruptly.

The employees knew their employer had financial troubles. A year earlier, Comm Comm lost its biggest client, VoiceStream, causing a brief layoff, and then struggled to obtain new business in late 2001 and 2002.

Employees, though, said the company was hiring even in the week before it shut down, making the surprise closure even more difficult to understand.

The employees sued for 60-days wages, claiming they weren't given notice before the layoffs. They also sought unpaid signing and performance bonuses, overtime wages, and reimbursement for unpaid medical bills.

In total, the former employees felt that Comm Comm owed them more than $1 million.

They soon encountered one of the key weaknesses of the WARN Act - identifying a solvent company that's obligated to pay what's owed to ex-workers.

To win their lawsuits, the workers had to prove that Barry Reese and Ralph Reese, the former owners of the parent company of Comm Comm, controlled and made the decisions that led to the shutdown.

Nearly four years after Comm Comm's sudden layoff, lawyers for the workers questioned whether they could legally hold the Reeses responsible. Weighing the odds, the attorneys negotiated a settlement of $170,000 for the displaced employees. About $10,000 was for unpaid bonuses, overtime, and medical bills.

The settlement included legal and administrative fees, leaving about $112,000 for the former employees to divide. That represented about 13 days of pay, well short of the 60 days required under the law.

Jeffrey Balicki, an attorney who represented Comm Comm and the Reese brothers in the WARN Act lawsuit, said the settlement was not an admission of wrongdoing by the former owners.

Mr. Balicki said the owners contended the sudden closure was necessitated by the fact that the company's lenders abruptly cut off the business' line of credit, a circumstance the owners could not have predicted.

"Clearly, it's a very defensible case," Mr. Balicki said. "They just settled because of where they were at the time in their lives with that litigation and just wanting to bring closure to it and retire and move on to other things."

Kathryn Sanborn, who was laid off by EPIX, an employee leasing firm in Tampa, Fla., accepted a severance-pay package that required her to waive her right to sue her former employer.

Severance waivers

One way that companies have avoided their responsibilities under the WARN Act is by requiring employees to waive their rights under the law when they are terminated in exchange for severance pay - without telling them they are entitled to up to two months wages under federal law.

The use of waivers by companies that want to escape WARN Act liability is a loophole that Congress should close, said John Philo, legal director for the Sugar Law Center for Social Justice, the nonprofit law center that publishes an annual guide to the WARN Act.

"Companies essentially are holding people economically hostage," Mr. Philo said. "If companies give one, two, three weeks' severance, people need it. They suddenly are being laid off. If they sign the waiver, they don't get the 60-days notice like they are entitled to. It really puts them in a Catch-22."

Kathryn Sanborn lived that conflict.

As a midlevel executive for EPIX, an employee leasing firm in Tampa, Fla., Ms. Sanborn was summoned to the human resources office on Aug. 27, 2002.

EPIX had decided to "downsize."

"I was one of 60. They took me to my desk and I packed up my personal belongings, and they walked me to my car," she recalled.

A week later, the employees who lost their jobs received an overnight letter with a legal document enclosed.

Former employees would be paid a week of severance for each year they had worked at EPIX - but only if they waived their rights to sue.

Ms. Sanborn signed and she received two weeks of severance pay.

Later, Ms. Sanborn contacted the Sugar Law Center.

"After checking with the [Department of Labor], we understand that EPIX is in violation of the WARN Act and we would like to pursue our legal rights," she wrote.

But because she and several other former EPIX employees had signed waivers, they could not prevail in court.

Stuart J. Miller, a New York City lawyer who specializes in representing workers in WARN Act lawsuits, said he encounters the problem regularly.

"When they call me, it is too late," he said. "Employees should not be allowed to release the company of his or her WARN claim without an explicit statement in the release that says there is a WARN Act and you may have a claim, and you are waiving that claim as well."

The plant-closing bill

Many of the issues that workers grapple with when they lose their jobs are rooted in the compromises made in 1988 as Congress fiercely debated what many called the "plant-closing bill."

To win passage of the WARN Act, Democratic U.S. Sen. Howard Metzenbaum of Ohio and his allies compromised - shortening the notice period from as much as six months to 60 days, exempting many small businesses, and allowing companies to avoid liability if they were seeking capital to remain afloat.

The WARN Act took effect without President Reagan's signature - the only bill in his two terms that became law without his signature.

"In cutting back enough to obtain a veto-proof margin, we obviously weakened the bill considerably," said James Brudney, a law professor at Ohio State University who was chief counsel for the U.S. Senate subcommittee on labor from 1987 to 1992.

The Government Accountability Office, the nonpartisan investigative arm of Congress, has examined the WARN Act twice.

In 1993 and again in 2003, the GAO found major flaws in the law and recommended Congress take action to reform it.

The 1993 report concluded that although workers under the WARN Act were more likely to get notice of an impending layoff or plant closing, many employers ignored the law and others did not give notice because of exemptions and loopholes.

Of the 650 major layoffs analyzed from 1989 to 1993, 415 were exempt from the requirements of the law, often because the layoff didn't impact at least one-third of a company's work force, a WARN Act requirement.

Shortcomings cited

The GAO's 1993 report recommended several changes to the law, most notably that Congress should consider giving the Department of Labor the power to enforce it.

But in 1994, the GOP regained control of Congress and the new majority had no interest in strengthening a weak, worker-protection law.

A decade later, another GAO report found many of the same shortcomings.

The 2003 study focused on 2001. It found that only one-quarter of the 8,350 plant closures or mass layoffs that year were subject to the WARN notice requirements.

Only about one-third of the employers provided proper warning in the instances in which notice was required, the study found.

As a result, GAO recommended Congress consider amending the WARN Act to simplify the calculation of when companies had to provide notice and make the law more precise.

The study also said the Department of Labor should educate employers and workers about their rights and obligations under the law.

Since its passage in 1988, there have been numerous attempts to reform the WARN Act and make it more effective.

In March, 1994, Mr. Metzenbaum offered the most significant makeover of the WARN Act. He proposed:

w Extending the notice period from 60 to 90 days for the largest layoffs.

w Providing WARN protection to more employees by lowering the minimum number of layoffs that trigger notices and including part-time workers in that calculation.

w Allowing the Department of Labor to bring lawsuits on behalf of displaced workers.

But Mr. Metzenbaum's efforts to amend the WARN Act never gained traction in the Senate. He did not seek re-election in 1994.

Ten years later, U.S. Sen. Tom Daschle, a Democrat from South Dakota, introduced a bill aimed at restricting the move of jobs from the United States to other countries. The proposal included changes to the WARN Act.

Mr. Daschle, the Democratic leader in the Senate, was joined in his reform effort by a number of Democratic senators, including Ms. Clinton and Mr. Edwards.

The bill would have expanded the number of workers covered by the law, extended the notice period to 90 days, required employers to educate workers about their rights under the WARN Act, and forced employers to provide notice when moving jobs overseas.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce fought the changes, the bill died, and Mr. Daschle was ousted in his re-election bid in 2004.

"The legislation contained several measures designed to strengthen the WARN Act and remove loopholes that had left so many workers without its protections," Ms. Clinton said in a statement to The Blade last week.

Mr. Obama, when he was a member of the Illinois Senate, worked to increase enforcement of the WARN Act by requiring the Illinois Department of Employment Security to annually notify employers of their responsibilities under the WARN Act.

"Now, I believe we must act at the federal level to close the loophole that allows employers to disregard the WARN Act without penalty," Mr. Obama said last week in a statement.

Early signs of trouble

In the 1980s, as a wave of plant closings around the nation hit the Midwest and Northeast especially hard, Greg LeRoy worked for a Chicago-based group that tried to keep factories open.

Mr. LeRoy recently told The Blade he and other veterans of the movement saw problems with the WARN Act when it took effect in 1989.

The 60-day notice requirement isn't long enough for communities to try to save a plant from closing and the loopholes are big, said Mr. LeRoy, president of the Washington-based nonprofit group Good Jobs First.

"To us, those were quite predictable when the dust settled on the very watered-down version of it," he said.

Robert Baugh, a high-ranking official at the AFL-CIO, has used plant closing data to document the number of jobs lost because of international trade.

Mr. LeRoy and Mr. Baugh have not given up hope that Congress, now controlled by Democrats after 12 years of Republican rule, will reform the law.

"I want to make it stick," said Mr. Baugh, who is executive director of the AFL-CIO's Industrial Union Council. "I want it for smaller firms. There should be some teeth in this thing."

Ohio's Senator Brown - a member of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions - said the changes he is studying include giving the Department of Labor enforcement power, making more companies covered by the notice requirements, and perhaps boosting the penalty for employers that violate the WARN Act.

Tom Kummerer is among the workers across the nation who hope that Congress takes action to close loopholes in the law.

Mr. Kummerer began working for National Machinery Co. in Tiffin in 1977 and worked his way up from the boiler room to the purchasing department.

He lost his job without notice when the plant closed in December, 2001.

"I just feel like there is too much of this going on underneath the radar in the United States. Something has to be done to stop it," he said.

Contact James Drew at:jdrew@theblade.com or 419-351-2004.