WITHOUT WARNING: Effects and reform of the WARN Act

Tiffin workers discover limits of WARN Act

Class-action lawsuit yielded meager payout

7/16/2007

We had some other big employers in Seneca County, but [National Machinery] was the best place to work, says Mark Griffin, a 38-year employee of the Tiffin company.

king / blade

Second of four parts

Gene Goshe had worked at Tiffin’s National Machinery Co. for 32 years when the plant closed without notice in 2001.

TIFFIN -- Four days after Christmas in 2001, Gene Goshe braved the brisk cold as he walked to his newspaper box and unrolled his copy of the Tiffin Advertiser-Tribune.

"National shutting down," blared the headline in tall letters across the front page.

In seconds, Mr. Goshe's life changed forever.

After devoting 33 years of his life to the National Machinery Co., Mr. Goshe read in the newspaper that morning that the plant had abruptly closed. He didn't get a phone call to let him know he no longer had a job.

"It was like a snowball hit you in the hind end on the first of January," recalled Mr. Goshe, then 58. "This is the way we are going to start the year."

The sudden demise of National Machinery stunned Tiffin, a town of 17,000 about 55 miles southeast of Toledo already reeling from plant closings and layoffs.

The plant, a few blocks from the small downtown, made the machines that made nuts and bolts since the 1880s. But while the products of its machines embodied the ordinary, the storied history of National Machinery was far from typical.

"The National" -- as locals affectionately called it -- provided a choice working environment for generations in and around Seneca County, a flat, fertile part of northwest Ohio dotted with fields and woodlots.

READ MORE: Effects and reform of the WARN Act

VIDEO: The Blade talks with Gene Goshe and Joe Poignon about their years at Tiffin's National Machinery Co. when the plant closed without notice in 2001.

The company's reputation as an exceptional employer was rooted in its traditions - a club for employees who had worked there at least 25 years, summer picnics at Cedar Point, and Christmas parties at the fancy Ritz Theatre.

National Machinery was like family, workers recalled. Not surprisingly, it was begun by Tiffin's first families -- the Frosts and Kalnows, whose ownership dates to the 1880s, when patriarch Meshech Frost convinced the company's original owner to move its operations to Tiffin.

The Frosts, and later the Kalnows, are recognized as Tiffin's leading community boosters, using some of their vast fortune to support local causes and institutions, including the city's Heidelberg College, where the families set up scholarship programs to benefit the children of National Machinery employees.

More than 500 workers lost their jobs in the sudden shutdown of National Machinery. When the plant reopened under new ownership, many were not recalled.

A fractured bond

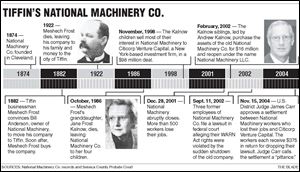

The bond between the privately held company and its workers changed forever on Dec. 28, 2001 - the date National shut down.

For most of the 549 National Machinery Co. employees, there was no notice the place where many of them had dedicated their working lives was closing.

Paul Aley, National Machinery's president, explained to workers in a letter dated the day the plant closed that banks cut off the company's money because of its financial troubles. Most employees didn't receive Mr. Aley's letter until they had already read about National's demise in the newspaper or heard about it from friends or co-workers.

In 1988, Congress passed a law requiring business owners to give 60-days notice before a plant closing or mass layoff. If National Machinery Co. had followed the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act, known as the WARN Act, its employees could have begun looking for new work and putting their finances in order instead of dealing with the shock of suddenly losing their jobs.

There were concerns about the well-being of National Machinery Co. leading up to its closure. Citing financial problems, the company announced some layoffs earlier in 2001 and gave most of its workers the holidays off without pay. But the veteran workers expected business would pick back up as it had many times over the years.

This time wasn't like the others.

Hoping for better times

In the weeks and months after National Machinery's shutdown, employees looked to their faith for strength.

Twice a week, employees such as Mr. Goshe, a Vietnam veteran and father of four, would gather outside the plant at noon and form a prayer circle with 50 to 75 people. In the cold January and February air, they would pray for each other and for the future of National Machinery Co.

"Everybody would go around and if anybody had something to say, they'd say it, or they would say a prayer," Mr. Goshe said. "If anybody had anything they wanted to get off their chest, they could get it off their chest."

The local newspaper informed many National Machinery workers that their jobs no longer existed. Workers did receive a letter from the company dated the day of the plant closing.

The workers took pride in their roles in National Machinery's history and held out hope for a return to better times.

"National Machinery had the knowledge in town that they were the best employer in Seneca County," said Mark Griffin, a 38-year employee. "We had some other big employers in Seneca County, but that was the best place to work.

"They took care of their people, they had a fair wage, you worked your overtime, had a great retirement, and they took care of you," Mr. Griffin said.

From its Quarter Century Club, which honored employees of 25 years, to its picnics, baseball leagues, and community service, National Machinery was steeped in tradition.

Its owners, the Frosts and Kalnows, who for decades referred to their employees as "Our people," instilled an unapologetic sense of family in and outside the plant.

They provided quality employment, fair wages, and steady jobs, and in return they expected their workers to live up to National Machinery standards to protect the image of the company. Employees in the 1970s and '80s were expected to be clean-cut and trouble-free. They were forbidden from cashing their checks at local watering holes.

Mr. Griffin said National Machinery employees had enough pride in their work to cash their checks at a bank, not at a bar.

In return, Mr. Griffin said, "If you got into trouble or were a little short, they would always bring the money up ahead of you. They would pick you up and you could pay 'em back later. It was like a family thing."

A Tiffin institution

National Machinery began four generations of ownership by the Frost and then Kalnow families soon after Meshech Frost convinced Bill Anderson to move the company to Tiffin in 1882.

In Tiffin, there is much folklore about National Machinery and its family ownership.

One tale is that Mr. Frost went to New York City to get a loan from financier "Diamond" Jim Brady to help purchase the company.

After his death in 1922, Mr. Frost left the company to his son, Earl Frost, who ran it into the 1950s. Earl Frost's daughter, Jane Frost, who was the heiress to the family fortune, married Carl Kalnow, a banker, and together they owned National Machinery Co.

National Machinery employees still fondly recall the story behind the Frost-Kalnow engagement.

"From what I know, Mr. Kalnow came to town and he got off the train and asked who the richest man in town was and if he had a daughter," Mr. Griffin said. "It was Miss Frost and he ended up marrying her."

The Kalnows had four children -- Carl, Andrew, Gertrude, and Loretta - who inherited National Machinery after their mother's death in 1986.

In 1998, the Kalnow siblings -- who were raised in Tiffin but had moved away - sold the company for $98 million to Citicorp Venture Capital, a New York-based firm that buys and sells companies as investments.

Within three years, National Machinery rapidly declined from a thriving company to an abruptly shuttered one.

![REG-NATIONAL24P-10-jpg.jpg ‘We had some other big employers in Seneca County, but [National Machinery] was the best place to work,’ says Mark Griffin, a 38-year employee of the Tiffi n company.](/image/2012/10/25/300x_b1a4-3_cCM_ca0,2,1047,957/REG-NATIONAL24P-10-jpg.jpg)

‘We had some other big employers in Seneca County, but [National Machinery] was the best place to work,’ says Mark Griffin, a 38-year employee of the Tiffi n company.

A different company

After National Machinery closed, the Kalnow siblings - who had kept a seat on the company's board of directors and a 15 percent stake in the business as part of the sale - became the workers' best hope for rescuing the company.

In the weeks after the company closed its doors, the Kalnows, led by Andrew Kalnow, founder of Chicago-based Alpha Capital Partners, a private equity investment firm, began negotiating to buy National Machinery's debt from a consortium of banks holding tens of millions of dollars in notes - the debt taken on to buy the company from him and his family.

In February, 2002, the Kalnows repurchased National Machinery for $16 million, just a fraction of what they had sold it for just three years earlier.

In Tiffin, many employees believed their prayers were answered.

But they soon learned that National Machinery, under its new ownership, would be a far different company than the one they had devoted 20, 30, or even 40 years of their lives.

In a complex business transaction, the Kalnows established National Machinery LLC, or limited liability company, which they used to essentially purchase the property and assets of the former National Machinery Co.

The sale was completed in such a way that the new company would inherit the old company's headquarters in Tiffin, its factory, its machinery, and its customers. But it would have no responsibility to pay the debts of the old company. Those debts included millions of dollars owed to suppliers and $1.5 million more owed to area doctors and health-care facilities for medical services provided to former employees before the plant closed.

Officials of the new company eventually agreed to pay an undisclosed amount toward the $1.5 million in medical bills owed by former plant workers. But the new company said it had no legal obligation to the employees of the "old company," who were left behind when the plant closed in December, 2001.

A spokesman for National Machinery LLC last week said WARN Act issues were handled by the former plant owner and their lawyers.

"Like many other companies today facing the challenge of being successful in a highly competitive world market, National Machinery LLC is leaner and less vertically integrated," said John Bolte, senior vice president of operations and human resources. "Many processes and therefore jobs from the past simply do not exist in our company in order to make us more competitive."

Attempts by The Blade to interview Andrew Kalnow and his siblings were unsuccessful.

In an e-mail from Mr. Kalnow last month, he told The Blade: "It seems like you have a politics agenda in mind that has nothing to do with our business and contribution to the community."

Workers get down to business at National Machinery Co. in 1974. The plant, a few blocks from downtown Tiffin, began operations in that Seneca County community during the 1880s.

A sense of betrayal

The Kalnows' "new company" -- National Machinery LLC -- in the spring of 2002 hired nearly 240 full-time employees after it reopened the plant, many of whom worked for the "old company."

But many of National Machinery Co.'s 549 employees, including some of its longest-tenured workers, such as Joe Poignon, never received the call to come back.

"They started it back up, but they excluded us," said Mr. Poignon, a 40-year employee who worked in the company's after-market section. "There was people who weren't retired out there who had more than 25 years of service and they were not called back."

Some grew bitter, angry, and depressed as they waited and waited for the call from National Machinery that never came.

"It's the way they treated us," said Mr. Poignon, who tries to avoid Greenfield Street in Tiffin, where National Machinery is located. "Not calling us in to inform us of anything, and not being up front and square with us, and being ostracized after they reopened the plant. None of us deserve that. After we have given our lives to it, our good working years are gone. We can't go out and restart. We gave them all our good working years."

He added, "You feel like you've been betrayed."

Depression and anger

Several former National Machinery employees fell into depression as they tried to live without the work they had been doing for most of their lives.

Others were angry.

Joe Poignon, a 40-year National Machinery employee, was among the many workers who were not called back when operations resumed at the Tiffi n plant under new ownership.

Paul Martorana, a 27-year employee of National Machinery, returned to the company's offices to settle his pension after the new company had taken over. But before he left, he had a request of Anne Martin, the company's secretary.

"Would you do me one favor?" Mr. Martorana recalled asking. "Take my picture off the wall. I don't want anyone to know I was ever associated with this company."

Mr. Martorana wanted his picture taken off the walls of National Machinery Co.'s Quarter Century Club. The club, which had more than 735 members since it was established in 1936, honored the company's most loyal employees.

Many members of that devoted club were among those who were unexpectedly thrown from their jobs, instantly losing health-care coverage, paychecks, accrued vacation time, and the stability of employment.

"A lot of people got hurt, financially and mentally," Mr. Martorana said.

"We didn't know what to do," Mr. Poignon said. "There were people who were scheduled for surgery. They didn't know what to do. They didn't have insurance. Some of them had cancer."

Picking up the pieces

It was difficult, if not impossible, for some former employees to find reliable work after decades with National Machinery. The employees had no time to plan, find new jobs, or train for new careers.

Out of necessity, some took whatever they could find, accepting steep pay cuts and losing benefits.

"It's basically turned our lives upside down," said Sharon Goshe, who has been married to Gene Goshe for 34 years.

‘A lot of people got hurt, fi nancially and mentally,’ Paul Martorana, a 27-year employee, says of National Machinery’s closing. He and other ex-workers later sued, citing the WARN Act.

Mr. Goshe said he held out hope for about three months after the plant closed, hoping that he would get a call to return to work. The call never came.

"Once they opened back up and [I'd] seen the ones they were hiring back, I was too old," Mr. Goshe said.

He began applying for nearly "any job that was in the paper," but he didn't have any success and began to suffer from depression.

"The unemployment was running out, and we got the same old stories," he said. "You go out and you look for a job and you get your hopes up, and you hear nothing."

Ten months after National closed, Mr. Goshe took a job for $10 an hour with no benefits at a local lumber yard, a $4 an hour wage cut.

Many employees of National Machinery skipped their paid vacations over the years, believing they had accrued months of paid time off that could be used in the future. When the old company shuttered, employees were not reimbursed for the time.

The workers said they were also owed thousands of dollars in lost wages and unpaid medical bills. But when they went to the plant office and tried to collect from National Machinery LLC, they heard a familiar refrain: "Sue the old company."

But the "old company" no longer existed.

Taking legal action

On Sept. 11, 2002, three former workers of National Machinery Co. -- Chad and Donald Baker and Paul Martorana - filed a class-action lawsuit in federal court in Toledo on behalf of all the workers who lost their jobs.

They sued National Machinery Co., Citicorp Venture Capital, and two related entities claiming the WARN Act was violated when the plant closed without a 60-day notice. They asked for lost wages, vacation pay, and medical expenses they said they were owed, totaling at least $4,000 per worker.

They received a quick education into the limitations and loopholes of the federal law.

But the biggest obstacle they faced was the wall of legal agreements, contracts, and documents set up by a squad of lawyers to make sure that National Machinery LLC was not responsible for the debts and actions of National Machinery Co.

Attorneys for Citicorp Venture Capital argued that their client wasn't the liable employer under the law because even though Citicorp was the majority owner of the "old company," it didn't make business decisions on behalf of National Machinery.

Because the "old company" was now a mere shell, its former employees fell into one of the most prominent pitfalls of the WARN Act - finding someone who could pay the workers what they were owed.

Nearly three years after the company closed, attorneys for the employees and Citicorp Venture Capital agreed to a settlement that would pay $375 per worker before taxes - just pennies on the dollar of what most employees felt they were owed. National Machinery LLC, as a completely new entity, had no obligation to the workers and was not involved in the settlement.

Ten months after National Machinery shuttered in 2001 and laid off hundreds of workers, Gene Goshe took a job for $10 an hour with no benefits at a local lumberyard.

An 'insult'

Calling the settlement an "insult" and frustrated with the law, 74 former National Machinery employees wrote the judge to object to the settlement.

"There were a lot of very good employees that were completely devastated when all this happened and some satisfaction needs to be given to all of us," Virginia Coffman wrote. Mrs. Coffman, along with her husband, John Coffman, worked for National Machinery Co. for more than 28 years. "This type of treatment cannot be allowed to go unnoticed and just slide by, it has hurt many responsible people who are still trying to recover."

In a handwritten note, Steven Webster, a former National Machinery employee from Upper Sandusky, Ohio, explained that the company's sudden closing triggered a financial tailspin that caused him to fall behind on child-support payments. Mr. Webster explained that he needed to withdraw from his 401K plan twice to keep banks from foreclosing on his home.

"For the six months I was without a job, I had my water, electric, and gas shut off and had to live with my mother for a while until I got a job because I couldn't afford food or anything," Mr. Webster wrote.

Many of the workers sent copies of their letters to their representatives in Congress and the Statehouse, including U.S. Rep. Paul Gillmor (R., Tiffin), U.S. Sens. George Voinovich and Mike DeWine, then-Gov. Bob Taft, and state Rep. Jeff Wagner (R., Sycamore).

None of them was willing to fight for their constituents, at least on the WARN Act.

On Nov. 15, 2004, a group of former National Machinery Co. employees went to federal court in Toledo to object in person to the proposed settlement.

On their day in court, U.S. District Judge James Carr empathized with the plight of the workers, inviting them to sit in the jury box and address the court. But the judge all but told the workers that his judicial powers were limited by a law with no teeth.

In the end, Judge Carr reluctantly approved the settlement, declaring it a "pittance" and telling angry workers it was the best settlement they could hope for under the weak federal law.

"Most simply put, and most unhappily, you're out of luck," Judge Carr told the workers. "That statute has proven to be no protection to you."

Lingering bitterness

In Tiffin, more than five years after the "old company" suddenly was closed on a cold December day, time has healed some of the wounds. But there still remains an undercurrent of regret and bitterness.

Today there's a sign outside the headquarters of National Machinery LLC that proudly proclaims it as a 130-year-old company.

The former employees never called back by the "new company" say the sign epitomizes the hypocrisy of what transpired at National Machinery.

"What I've heard is they think they've done great - 'they've saved the company,'" Mr. Poignon said. "You don't want to think that the place you've worked your entire life has done something terrible. They didn't fulfill their promises to a lot of people who gave their whole lives to the company."

The laid-off workers have struggled to come to terms with the fact that National Machinery LLC - which conducts its business from the old headquarters of National Machinery Co. in Tiffin, builds the same machines, and serves the same set of clients - wasn't legally required to pay their lost wages and benefits.

Some recognize that Andrew Kalnow may have saved National Machinery, but they question why the rescue couldn't have been performed more humanely, taking into account the loyalty of many of the company's longtime employees.

They believe Meshech Frost and Jane Frost Kalnow would be disappointed.

"It's all about putting money in your pocket," Mr. Poignon said. "Maybe morality has changed. Maybe young people think this is OK. But in our day, this wasn't a moral thing to do. If you look at the business side of it, it looks pretty good.

"But if you look at the human side of it, there's been a lot of damage."

Contact Steve Eder at: seder@theblade.com or 419-304-1680.