American Airlines' ' Brat Pack' now CEOs

In dawn of deregulation, '80s grads rose to top

1/6/2012

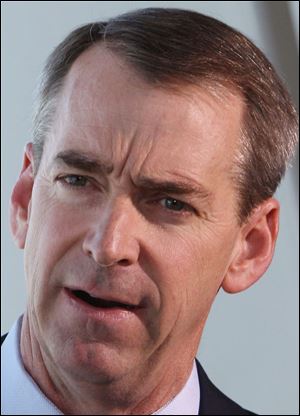

David Cush, CEO of Virgin America

ASSOCIATED PRESS

Spirit Airlines CEO Ben Baldanza

NEW YORK -- From an office at the end of a Dallas runway in the 1980s, the modern airline business was born.

There, in cubicles with thin, gray carpet and shared computers, young graduates of the top business schools were tasked with making sense of deregulation -- a new era when the government no longer dictated routes or prices.

Under American Airlines' then-chief executive officer, Robert L. Crandall, they issued the first frequent flier miles, developed the hub system, and found a way to fill empty seats with deeply discounted fares. Standards were high. Perfection was demanded. Those who excelled were quickly promoted, regardless of how young or new to the company they were. At the time, being a financial analyst on the second floor of American's headquarters was unlike any other job in the industry.

Today, four of them run airlines -- including American.

"It was a magical time," Virgin America CEO David Cush, 51, says. "You didn't know where these guys were going to end up, but you knew you were hanging around with a bunch of smart guys."

US Airways CEO Doug Parker, 50, and Spirit Airlines CEO Ben Baldanza, 50, got their start alongside Mr. Cush.

Tom Horton, the other member of this airline Brat Pack, arguably hit it even bigger -- taking over as CEO of the airline where they all started.

David Cush, CEO of Virgin America

The 1980s "was sort of a golden moment for American," says Michael Useem, director of the Center for Leadership and Change Management at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School.

Today, American struggles with old jets and high labor costs. Once the largest airline in the world, American is in third place behind Delta Air Lines Inc. and United-Continental Holdings Inc. But the most painful jab for the carrier came in November when American's parent, AMR Corp., sought Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection -- the same day it promoted Mr. Horton, 50.

American's success at molding future leaders echoes the success of big companies such as General Electric and Procter & Gamble. Those companies were known to weed out underperforming executives and give those who showed promise extra responsibilities.

"These companies made developing great leaders a defining element of their DNA," Mr. Useem says.

American didn't just create CEOs. Dozens of its young financial analysts from the 1980s went on to become top executives at most of the major airlines. Others held senior roles at travel companies including Orbitz and Royal Caribbean.

They all came to American because it was the center of innovation in an industry on the verge of a revolution. These young analysts were driven by their bosses and each other. And nobody pushed harder than Mr. Crandall.

"The most competent got promoted very rapidly," says Mr. Crandall, who retired in 1998. "That made American a very good place to work. And the consequence of that is we attracted a lot of very, very bright people."

US Airways Chairman and CEO Doug Parker

Three decades later, most still recall the CEO's persistence.

The worst thing you could do was say you didn't want to waste his time with the details. Mr. Crandall thrived on those details and demanded them of his staff. He was known to quiz station managers on how much they spent on rags. If they didn't know, they were told they didn't really understand their operation.

"They didn't care if you were too young or didn't have enough years of experience. All they cared about was if you were competent and able to do a good job," says Bernie Han, who worked at American from 1988 until 1991. He later became the chief financial officer at America West and then held that title at Northwest. He is now chief operating officer of Dish Network.

American's headquarters was an energetic place. Competition was fierce but friendly. The analysts often bounced ideas off each other while playing Nerf basketball in a cubicle.

"If somebody did good work, the other guy wanted to do better work," says Jeff Katz, an American alumnus who went on to become CEO of Swissair, then led the online travel company Orbitz before landing the top job at Nextag, an online shopping Web site.

Despite being at competing airlines today, many former American analysts still keep in touch. From the start, they were a social group.

American Airlines President and CEO Tom Horton

After work, they drank beer at the Euless Yacht Club -- a land-locked dive bar that was the closest place to headquarters. Other nights, it was margaritas at Esparza's, a nearby Mexican restaurant.

There were Texas Rangers games, a basketball league that Mr. Parker played in, and the occasional lunchtime trip to Sonny Bryan's Smokehouse.

"We were all single and many people met their spouses there," says Teri L. Brooks, who rose to head human resources at American before leaving in 1996. She started the same year as David Brooks. Five and a half years later, they were married. He now runs American's cargo division.

Working at an airline meant free flights. Thursday night or Friday morning, a weekend destination was selected -- New York, London, the Caribbean, or skiing in Utah.

"We'd all pile into hotel rooms, sleep on the floor," Mr. Brooks says.

Sometimes a random gate was picked. The plane might be heading to Cancun or Kansas City. Fate would decide.

"I was never a fan of that game," says Mr. Cush. "It never worked out very well."