U.S. law, 6,000 miles separate child, parents

11/30/2000

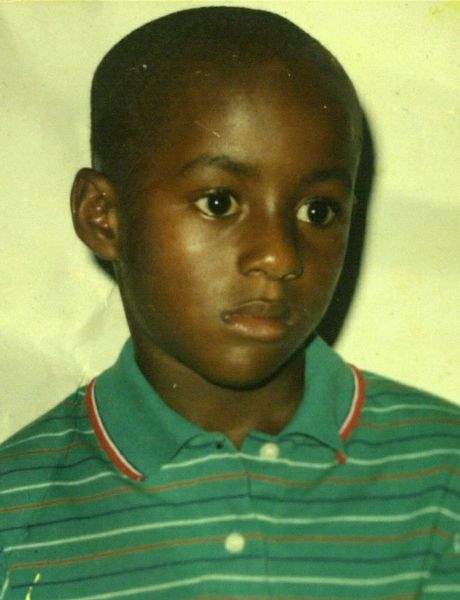

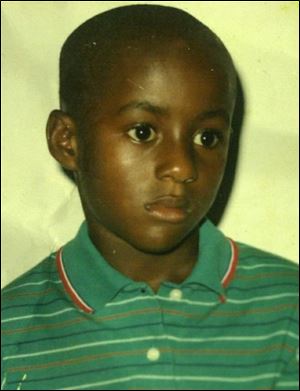

Francis Nmah

Margaret, right, and Gabriel Nmah have a 16-month-old daughter, Delores, in her father's lap, whom Francis has never met.

The tears start a slow, steady stream down Margaret Nmah's face almost as soon as she starts talking about the 9-year-old son she hasn't seen for more than two years.

She and her husband, Gabriel, left the post-civil war strife of Liberia with the understanding that their son, Francis, would join them in Toledo as soon as they had enough money to send for him.

But since 1998, Francis has remained 6,000 miles away in the unstable West African country, ensnared by a U.S. immigration law that might keep him separated from his parents for four more years.

"It's very terrible," Mrs. Nmah said as she cried. "Sometimes, I feel like my son is dead. When I talk to him, I feel sick and depressed. I really want my son. I feel like I'm a bad mother."

Mrs. Nmah, who won a visa lottery in 1998 for her family, said Francis would have come to America with her and her husband, but they didn't have enough money. Millions of people from around the world apply for diversity visas, but only 55,000 are awarded each year, and the visas expire if not used.

Francis Nmah

The Nmahs were not able to raise the extra $1,500 required to bring Francis here. Family and friends urged the couple to move to the states and get jobs so Francis could join them soon after.

But the diversity visa that allowed them entry into the states expired shortly after they arrived in the fall of 1998. A subsequent request for a student visa that the Nmahs hoped would reunite them with their son was turned down in February, 1999.

Through attorneys who work for Advocates for Basic Legal Equality, the Nmahs petitioned the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service for humanitarian parole, which allows entry into the country for urgent humanitarian reasons.

That request was denied in July.

A letter from Dennis Peruzzini, acting director of the INS's Rome office, said the facts in the case are unfortunate, but "do not constitute circumstances that would place the applicant in an urgent humanitarian category."

Mrs. Nmah said she never would have left Francis in Liberia with his aunt had she known it would be so difficult to get him into the country.

Apart from longing to have their son under their roof, they also want him out of Liberia, because they fear for his safety in a country where from 1989 to 1996 civil war has claimed 200,000 lives and left an estimated 1 million people homeless.

The country remains unstable. In June, the U.S. Department of State issued a travel warning to American citizens. The department prohibits dependents from accompanying government officials to Liberia.

Mrs. Nmah, who works as a dietary aide at the Sunset House nursing home, said she worries about her son's ending up in a dangerous situation. She also worries about his emotional well-being, because her sister often sees Francis off by himself crying.

His parents try to talk to the boy by phone every few weeks, but it can be difficult to get through. And when they do talk, Francis begs for his parents to send for him.

"I don't know what to tell him, because he's telling me that I'm lying to him," Mrs. Nmah said. "He says, 'Send the money for my ticket.' But he doesn't know what I have to go through."

The Nmahs feel like they're running out of options. ABLE has turned to U.S. Rep. Marcy Kaptur (D., Toledo) and Mike DeWine and George Voinovich, Ohio's Republican U.S. senators, to sponsor a special bill that would allow Francis to enter the country.

But while all of the legislators have sympathized with the Nmahs' plight, members of their staffs don't think a private bill offers the best chance for success.

Steve Katich, staff director for Miss Kaptur's Toledo office, said few private bills have a chance of passing.

"I think working with the system that's in place will be more effective than trying to pass legislation, which would be difficult at best," Mr. Katich said.

Miss Kaptur has intervened once by sending a letter to U.S. immigration officials in Rome in July asking them to grant the request for humanitarian parole.

Mr. Katich said Miss Kaptur plans to contact the INS again to ask it to reconsider its decision.

Staffers for Senators DeWine and Voinovich also rejected the idea of a private bill. A letter dated Nov. 7 from the senators' joint Columbus office said it "does not seem to us that the Immigration and Naturalization Service has done anything contrary to its mission in this specific case...."

Mike Dawson, a spokesman for Mr. DeWine, said that not many private relief bills pass Congress each year and those that do are usually "life-and-death situations."

"Otherwise, you'd have [private bills] for every INS case in the country, of which there are tens of thousands a year," Mr. Dawson said.

He said the senator's office will write the INS and push Francis's case. He said the office will try to get the boy a special visa so he can visit his parents during the holidays.

Mr. Voinovich will join Mr. De|Wine's request to the INS, according to Scott Milburn, a spokesman for the senator.

"It's a very unfortunate case," Mr. Milburn said. "As it stands now, it looks like INS has done an accurate following of the rules, but we're going to see what we can do."

Emiko Furuya, a fellow with the National Association of Public Interest Law who works in ABLE's Toledo office, said she thinks involvement by the legislators is crucial to getting Francis into the country.

Mark Heller, an ABLE attorney working on the case, said he's frustrated by the federal agency's stance on Francis's case. After all, he said, the boy will be allowed into the United States in about four years if his parents gain citizenship or through a different type of immigration petition that will take just as long.

Mr. Heller said the delay simply keeps Francis separated from his mother and father during a crucial period of his life.

"So what is the great loss for anybody here to just let him come in and be with his parents?" Mr. Heller asked.

Mark Hansen, district director of the INS office in Cleveland, said Francis's compelling story is one of many that can be told every year. He said the boy's parents and attorneys are not barred from trying to make their case again for humanitarian parole.

"There are only so many visas available, and, obviously, when the demand is greater than the supply, it creates a backlog."

The holiday season is particularly tough on the family, which now includes 16-month-old De|lor|es, whom Francis has not met. Mr. Nmah, who works at Pro-Pak Industries, said shopping trips have been abandoned, because seeing families having fun together triggers painful thoughts of a son who is so far away.