Rescue agency workers intervene for mentally ill

7/15/2001

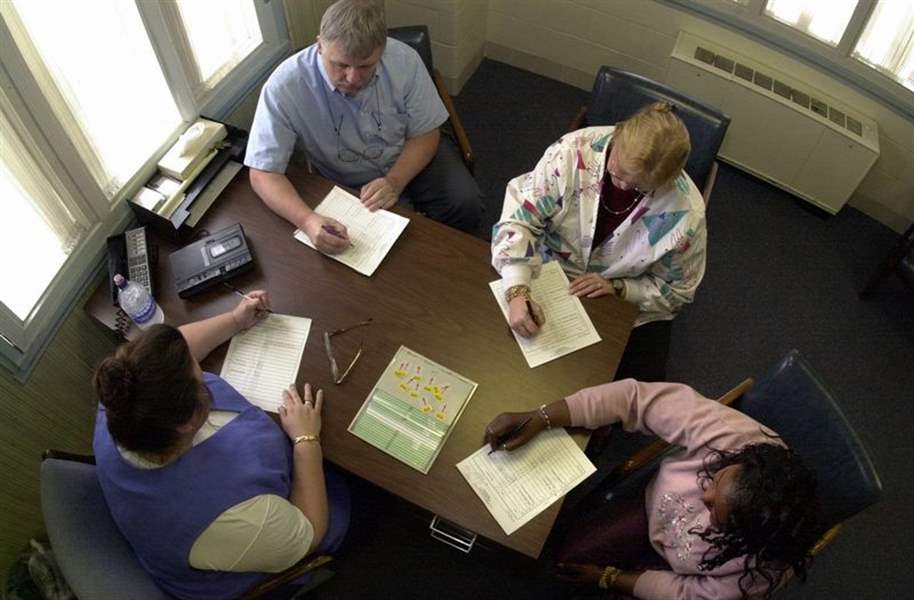

At shift change, staff members, from top, Steve Huber, Karen Adrian, Patricia Shipp, and Pam Henderson exchange notes.

Her mind is holding her prisoner.

Trapped in a fog brought on by mental illness and drug addiction, she stands in her doorway as Brian and Mike pull up. They're here to help.

Both work for Rescue Mental Health Services, the Lucas County agency that is the first responder in emergency mental health cases and responsible for coordinating disposition of each patient.

The agency treats or evaluates about 6,000 people a year, many of whom are repeat patients. One fourth of its patients are seen more than once a year and some are seen up to a dozen times or more a year.

Sometimes Rescue workers end up treating patients at their inpatient facility on Collingwood Boulevard, while other times they funnel patients to the county's private hospitals for treatment.

Today, Brian and Mike are out on a field assessment.

The West Toledo woman they are assessing has become agitated over the last few days, including shouting and yelling. Neighbors have complained. Brian and Mike enter the woman's apartment to talk with her.

The place is filthy. Dirt is on the floor, a mattress lies on the floor in one room, and holes have been punched in the wall. The woman is dressed in blue jeans, new tennis shoes, and a navy blue sweatshirt. She sits on her couch and looks straight ahead most of the time but occasionally glances at Brian and Mike, who are standing nearby.

She rambles, sometimes incoherently.

“Get these people off me, they're in my body,” she says.

Mike begins to question her: “Do you have any medication?”

“Yes, but it makes me sick,” she says.

Many people with mental illness must take medication to control their illness. With it, no one would suspect they have an illness. Without it, they can descend into the mental fog this woman is experiencing.

Illegal drugs, such as the crack cocaine this woman says she's taken, make matters worse.

Mike explains that he and Brian want to help her. Maybe she'd like to come to Rescue and talk some more, he asks.

“I don't want to answer any more of your questions,” she says suddenly. “Just leave.”

Mike and Brian leave the apartment and walk a few yards from the doorway.

“We can go ahead and pink slip her,” Mike tells Brian, who agrees with the assessment.

Without intervention, the woman could become a danger to herself and others, Brian says. “Pink-slipping” is mental health jargon for the process where those with mental illness are involuntarily committed to a treatment facility.

Brian begins jotting down notes on the pink form about the woman's behavior. Meanwhile, Mike begins to fill out other paperwork and calls Toledo police to come and get the woman.

A woman who has been evaluated at Rescue Mental Health Services rests in an interview room at the facility on Collingwood Boulevard.

“She knows what's happening next,” Brian says as he continues to write. The woman has been through the system before.

A short time later, three police cars and a police van arrive. They're not taking any chances. While those with severe mental illness are usually more dangerous to themselves than others, their behavior is unpredictable. She is taken to Flower Hospital without incident.

Brian and Mike, like all other Rescue workers, travel in pairs to back each other up. In the last 15 years, there have been only two cases of Rescue workers needing medical treatment after being assaulted by mentally ill patients. But the constant need to be on guard is stressful, said Rescue president Frank Ayers.

“There's always the possibility of something,” Mr. Ayers says. “That's what's stressful - not knowing what's going to happen.”

On his way back to Rescue's headquarters, Brian talks about his day. Although it's been pretty typical, he adds: “Every day is different.”

Among his past experiences: talking on the phone to a suicidal man with a gun to his head. Other times, he's been called in to evaluate a violent patient brought to Rescue by police, a patient who was ranting and confused, someone who because of mental illness doesn't even know where he is. Sometimes his job is just to listen.

Sometimes, talking is all that's needed; other times a stay at Rescue or a local hospital's psychiatric unit is necessary. Involuntary commitments aren't enjoyable, but “even if someone doesn't want help, you're doing some good,” Brian says.

Rescue helps others going through short-term mental crises. Rescue staff workers do their jobs in relative obscurity, and few people outside law enforcement, the medical community, and the clients and their families know about their service.

Mental health professionals estimate up to 2 percent of the population has a serious mental illness like schizophrenia. Each year, about 10 percent of the population has some sort of temporary crisis, such as dealing with a sudden or traumatic event such as a death in the family.

Despite those statistics, services like Rescue's are relatively new.

While every county in Ohio must have some sort of emergency mental health service, only large urban areas have services as advanced as those provided by Rescue, Mr. Ayers says. However, Rescue was anything but advanced in the beginning.

St. Patrick of Heatherdowns Catholic Church started a volunteer suicide prevention hotline in 1966. The program grew over the years and in 1980 the United Way and the Lucas County Mental Health Board decided something more was needed to deal with cases of emergency mental illness.

Rescue was formed in 1982 to act as the central agency coordinating all cases of emergency psychiatric illness in Lucas County. These are cases where a patient is suicidal, dangerous to others, psychotic, hallucinating, or having intense, short-term problems.

“We were organized to serve as a bridge so people did not have to go back into the hospital,” says Mr. Ayers.

In the 1980s, psychiatric hospitals began to move most patients into the community. Northcoast Behavorial Hospital, a state-run facility and the only local psychiatric hospital in Toledo, went from about 500 beds in 1980 to 45 beds for psychiatric patients today.

“As the beds went down, we got busier and busier,” Mr. Ayers says.

Today, Rescue has a $4.6 million annual budget, mostly funded by taxpayers through state tax revenue and a local county levy. The agency staffs a 12-bed adult unit and a five-bed child unit.

Rescue workers see about 550 patients a month. Of those in need of further treatment, about 130 are admitted to Rescue's adult crisis unit, 40 are admitted to the child/adolescent unit, 130 are admitted to private hospitals, and about a dozen are admitted to Northcoast Behavioral Hospital.

At shift change, staff members, from top, Steve Huber, Karen Adrian, Patricia Shipp, and Pam Henderson exchange notes.

Patients who need treatment stay - usually for two to three days - at Rescue for evaluation or are sent to local hospitals after being evaluated. It's a relationship that's unique in Ohio. Rescue and local hospitals work in partnership, which means mentally ill patients regardless of income can be treated at Lucas county's private hospitals.

Most patients - about 35 percent - at Rescue are self-referred or are referred by family. The rest come in approximately equal amounts from community mental health centers, hospital emergency rooms, and the police.

“We've had university professors, attorneys, doctors - the whole range,” Mr. Ayers says.

About 65 percent of Rescue patients have abused drugs or alcohol shortly before being seen by Rescue workers.

Like the woman taken to Rescue last month.

She had attempted suicide by overdosing on drugs. Hospital workers had saved her and she was taken to Rescue for evaluation.

Ivy, a Rescue worker, is in a room at Rescue with the woman. The room is quiet except for the hum of an air conditioner. Screens cover the plastic windows. The furniture is heavy and hard to move.

“Are you having suicidal thoughts? Do you want to hurt yourself?” Ivy asks.

“No,” the woman responds.

“Have you ever tried to attempt suicide?”

“Several years ago,” the woman says.

Ivy pauses briefly. She knows the woman doesn't remember her recent suicide attempt or is lying.

While confused at times, the woman seems quite intelligent. She talks about her career in the military. She mentions how making enough money has always been important to her; so important that she often worked months without a day off on construction jobs. Her problems with mental illness always seemed to catch up to her, though, and when they did alcohol abuse followed close behind.

“As long as I'm drinking, I never sleep,” she tells Ivy.

“When was the last time you slept?” Ivy asks.

“It's been a month,” the woman says.

Ivy asks a few more questions and asks the woman if there's anything she wants to add.

“You might want to know about the recent suicide attempt. I didn't tell you about that one,” she says.

When Ivy gently inquires when that was, the woman appears confused.

“I can't remember. Last week? I took a bottle of my Mom's sleeping pills.”

Ivy tells the woman that she will be treated at Rescue or a hospital, but Ivy's going to go downstairs and visit with the woman's family. Her mother and sister sit in a waiting room.

“Is she going home?” the sister asks.

No, Ivy says, she needs treatment.

“We've tried so many times to get her some help,” the mother says.

Mike comes into the office where Ivy is filling out paperwork and sits in a nearby chair. Although it's relatively quiet, Mike notes that “it can change in a minute, from nothing to three people all at once.

“We've had shifts where 18 to 20 people came in. It's just amazing.”

Mike points out that it's often more difficult on the family than the patient to deal with mental illness.

“A lot of times the family doesn't understand,” he says. “[But] a lot of people don't understand mental illness.”

Brian adds that many in the general public don't understand that a mental illness is just as real and potentially harmful as a physical illness.

“You have to understand that there's a great stigma yet of mental illness. People don't understand it, but almost anyone at one point in their life could be in a psychiatric crisis,” he says.

Ignorance often keeps people from seeking or receiving treatment, Rescue officials say. As a result, many people still remain trapped by mental illness - prisoners of their minds, waiting to be rescued.