Experts try to put flood fears on ice

3/21/2002WASHINGTON - Stow those life rafts.

The reported collapse of a Rhode Island-sized ice sheet in Antarctica is not the kind of polar ice cap melting that could raise sea levels and inundate coastal areas.

Experts agree, however, that collapse of the northern part of the Larsen B ice shelf is important scientifically and may be a red flag for ocean-level rises. “It is a big deal,” said Dr. Douglas R. MacAyeal of the University of Chicago. “But probably not for the reasons that the public thinks and fears.”

Dr. MacAyeal is an expert on icebergs who visited and studied the Connecticut-sized berg that calved from the Ross ice shelf on the other, colder side of Antarctica in 1999.

“The Larsen B incident has no implications for any immediate global sea-level rise,” Dr. Ted Scambos said yesterday. His group at the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado in Boulder announced the Larsen B collapse.

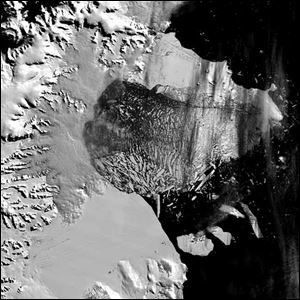

The Larsen B ice shelf, a large floating ice mass on the eastern side of the Antarctic Peninsula, has shattered and separated from the continent In this fourth of four images of the breakup taken March 5, 2002 by NASA's Terra satellite. The ice shelf has existed since the last Ice Age 12,000 years ago collapsed this month with staggering speed during one of the warmest summers on record there, scientists say. The collapsed area was designated Larsen B, and was 650 feet thick and with a surface area of 1,250 square miles, or about the size of Rhode Island.

Ice shelves are platforms of ice, often several hundred feet thick, that form where inland glaciers and ice sheets flow into the ocean. Ice shelves float in the ocean. Like ice cubes in glass of water, they displace a mass of water equal to their own mass.

So when floating ice melts, it does not raise water levels.

“The event is very important, however, in expanding our understanding of ice behavior in Antarctica,” Dr. Scambos added. “We now know that ice sheets are more sensitive to climate change than anyone thought. This is a very dramatic example of how fast a huge expanse of ice can collapse.”

Scientists are concerned about abrupt collapses because ice shelves act like the cork in a bottle. They help contain and hold back the flow of land-based glaciers and ice sheets. “Remove the bottleneck - the plug - and nobody knows the result,” Dr. MacAyeal said. “That ice covering the land could abruptly flow into the ocean, and that would have a dramatic effect on global sea levels.”

Both experts noted the Larsen ice shelf does not hold back massive amounts of land-bound ice that could rush into the sea.

Dr. Scambos said Larsen has been melting gradually and growing smaller since the late 1940s. Several huge sections have broken away in the past. One ice berg that calved in 1995 was 42 miles long and 15 miles wide.

The latest incident involved the single-biggest loss of ice in 30 years. Although 1,250 square miles of ice were discharged into the ocean, the event will cause no danger to navigation. The ice shattered into thousands of relatively small pieces that are expected to drift in the Weddell Sea, far away from commercial shipping lanes.

Larsen's retreat coincides with a 4.5-degree Fahrenheit increase in average temperatures in the Antarctic Peninsula over the last 50 years. The peninsula is a spit of land that stretches toward South America and has a much warmer climate than the mainland.

In contrast, the Antarctic mainland, which accounts for more than 90 percent of the south polar ice cap, has been getting colder during the last 35 years. Its average annual temperature is minus 56.2 degrees Fahrenheit.

The lowest temperature recorded on Earth was in Antarctica: minus 128.6 degrees Fahrenheit.

National Science Foundation research, reported in January, described Antarctica as the only continent where the climate is cooling. Scientists can't explain why.

“My big concern is whether this behavior, the melting trend, will continue to march south further into the continent,” Dr. Scambos said. “Then we could have significant sea-level rises.”

Dr. Scambos said scientists will use information about the Larsen ice sheet to fine-tune calculations about how the huge mainland ice sheets might behave if Earth's climate continues to warm.