Diversity is vital to success, new seaport director asserts

8/12/2002

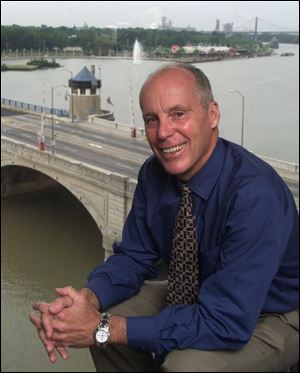

`We need to plan with zero-based thinking,' Warren McCrimmon, new seaport director, says in a port authority conference room, with the Cherry Street bridge in the background.

Boosting business at the Port of Toledo will require imagination and persistence, attributes that are vital to attracting new cargo, the Toledo-Lucas County Port Authority's new seaport director said.

“We need to plan ... as if we were starting all over again, and ask, `What do we want to be in the future?'” Warren McCrimmon said. “There are lots of things that go on ships that don't come through Toledo. There are a thousand possibilities. If you realize even a few of them, you're doing well.''

Describing himself as an optimist “with a stubborn streak,'' Mr. McCrimmon, 58, the former legal director and corporate secretary for the Vancouver Port Authority, has been on the job about a month.

While Vancouver's port is busier than Toledo, Mr. McCrimmon likes what he sees.

So does Phil Winteringham, the general manager of cargo-docks operator Toledo World Industries. He said his meetings with the new seaport director have been positive. “He's a nice, likable fellow. Give him time to learn the situation locally, and he should do a good job,” he said.

Vancouver's port handles more than five times the cargo by weight than Toledo. Its annual 73 million tons makes it the busiest tonnage port on the west coast of North America. But coal, grain, and other bulk commodities make up about 80 percent of the shipments at both ports.

In Vancouver, container shipments and passenger vessels account for the balance of port business, while Toledo's cargo profile rounds out with petroleum, fertilizer, and freight such as steel rods and aluminum ingots.

At one time, coal accounted for the vast majority of cargo handled at the Toledo port. Coal was shipped by rail from mines in southeastern Ohio, eastern Kentucky, and West Virginia and distributed by boat to mills and power plants throughout the Great Lakes.

Today, coal only amounts to about one-sixth of the 35.9 million tons handled during the record year of 1965. The reduction can be traced to the steel industry's decline, the substitution of nuclear power for coal, and the increasing use of cleaner-burning Wyoming coal in many remaining steam plants.

Steel's decline also has bitten into the iron ore volume across the Toledo docks.

Toledo port officials' response has been toward diversification, primarily by promoting a Foreign Trade Zone at the international cargo docks at the end of Front Street. One of the newest cargoes arriving at those docks has been German lumber.

Mr. McCrimmon said the diversity of cargo has helped Toledo. That's because the port is less vulnerable to the steel industry's fortunes than other ports, such as Cleveland.

A campaign led by John Loftus, the previous seaport director, to build overpasses at three problem railroad crossings on roads leading to the port has been important too, he said.

“For whatever the future of the port is, those things were critical,” Mr. McCrimmon said.

A three-month winter shutdown and ship-size limits imposed by the Seaway's locks and canals, whose dimensions were established in the 1930s, have long constrained overseas cargo growth at Great Lakes ports.

The “simple answer” to the winter shutdown is more icebreaking on the Great Lakes, Mr. McCrimmon said, “but I'm sure there's some politics involved on both sides” of the border.

Expanding the seaway for larger ships is a thornier problem, but not a difficult one, he said. One long-term possibility is construction of a “dry canal” like the one proposed to cross Guatemala as an alternative to the Panama Canal.

The Guatemala concept involves large crawlers that would hoist vessels and carry them along a right-of-way between drydocks on either coast. If the technology succeeds, a similar system could be applied to parts of the Seaway system, Mr. McCrimmon said.

“For very long-term thinking, you need to get your mind out there a little,” he said.

A 1971 graduate of the University of British Columbia Law School, Mr. McCrimmon worked in private practice from 1972 until 1983, when he joined a regional office of the Canadian Department of Justice as an attorney specializing in aboriginal claims negotiations.

In 1989, he was hired by the Canada Ports Corporation as its vice president for property, insurance, and legal affairs. His work for the Vancouver Port Authority began in 1991 and ended last year, when he stepped down at the request of a new port administrator who wanted to appoint his own staff.

Since then, he has been a self-employed consultant.