Another Ohio claim to fame: weirdness

2/21/2003

Genoa's `Little Building' is the only outhouse on the National Register of Historic Places. It was built in Civil War days.

Ohio is one weird place.

Ohioans enjoy racing their lawnmowers, worms, piglets, and in summer in North Baltimore, snowmobiles. Ohio is home to America's Most Perfect Tree, a 200-year-old hard maple in Waverly, and the Nation's Funniest Intersection.

With attractions like these, who says Ohio is just “fly-over country?”

Neil Zurcher, a Cleveland TV personality, made a living out of ferreting out Ohio's biggest, smallest, tallest, fattest, or just plain bizarre things. He didn't really have to dig too deep to find Ohio's wide, wild streak of weirdness. And in 2001, he wrote the book on the where and when: Ohio Oddities, a Guide to the Curious Attractions of the Buckeye State, details many of them.

Strange things and people seem to happen here.

In Port Clinton, they drop a huge walleye fish sculpture at the stroke of midnight each New Year's Eve.

In Findlay, the city's souvenir of the 1898 Spanish-American War is the captain's bathtub from the USS Maine.

Ohio is home to a vacuum-cleaner museum, motorcycle demolition derbies, the world's biggest mousetrap, and the annual Twinsburg Twins Days, an international gathering of up to 3,000 sets of twins.

By now everyone's heard of Cleveland's Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. But how many have visited the Accountants' Hall of Fame in Columbus?

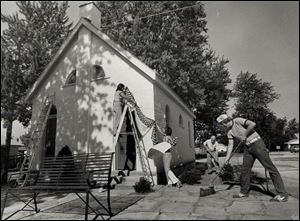

And did you know Genoa is home to the only outhouse on the National Register of Historic Places? It's true: the 12-hole brick privy was built in Civil War days to accommodate the boys and girls of a school nearby, but had since been turned into a storage shed. When the National Register people came around looking for listings, the city fathers found this was the oldest surviving building in town. They cleaned it up, put on a coat of paint, and landed on the historic map.

Even people who aren't alive anymore hang out here. Houses, factories, jails, colleges, and cemeteries all over the state supposedly host ghosts and poltergeists. National Web sites like www.theshadowlands.net and www.prarieghosts.com list them by the dozen.

Ohio stands out for its morbid fascination with dead people and body parts. (This is the place, after all, where a herd of buzzards supposedly flies into Hinckley each March 15.)

Maybe it was the air, or the flatness, or just plain old boredom that made doctors Estey and Bud Yingling collect and display all 100 or so pins, watch chains, coins, and buttons they retrieved from the ears, noses, stomachs, and throats of two generations of Lima residents.

Generations of Bowling Green children have marveled at The Three Fingers of Mary Bach, a gruesome piece of pickled evidence left from an 1881 ax murder. The homicidal Carl Bach was hanged in front of the courthouse on the last day of the county fair, Wood County's last public execution. You can see the fingers at the Historical Society museum, along with the corn-cutter knife that did the deadly job, the noose that brought Bach to final justice, and a couple of tickets to the big attraction.

In the 1930s, a series of 13 horrific dismemberment killings went on for four years in Cleveland. Even with FBI ace Eliot Ness investigating, the “Torso Murderer” was never found. Cleveland police have crude plaster casts of four of the victims' faces on display at a special museum.

In East Liverpool, you can see an embalming exhibit and the death mask of gangster Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd, who was gunned down at a nearby farm in 1934.

Then there's William Quantrill, a very bad man from Dover; his “Quantrill's Raiders” terrified post-Civil War settlements and murdered hundreds. He died in a Louisville prison, and his body was subsequently dug up by family members. Through a strange series of events, the Dover Historical Society ended up with his skull. Before burying it, they made a cast-clay replica of his head for display in the society museum.

“During the hot days of summer, water would bead on the surface, making it look like the head was alive and sweating,” Mr. Zurcher wrote. “The head was removed to a refrigerator, where it can be seen upon request.”

Maybe the most bizarre of all is the story of “Eugene,” an unknown 50-something African-American man who died in Sabina, Clinton County, in June, 1929. No one in town could identify him; the coroner ruled out foul play; the body was embalmed, and alerts were sent out throughout the state.

Months went by, and the body stayed at the Littleton Funeral Home. Police put it on display in a small outbuilding, hoping a passing stranger might recognize the dead man.

“By this time,” Mr. Zurcher writes, “word spread, people came from all over to view the remains, which by this time were spruced up with a new set of clothes ... Next thing you know, 35 years had gone by.”

An estimated 1.3 million people had a look at Eugene, but no one could say who he was. Finally, the funeral home decided it was time to put the old body to rest. In 1964, he was interred at Sabina Cemetery.

But on a happier note, there's that funny intersection, a place that might have meant something to Eugene. According to State Farm Insurance Co., it's in West Chester, Ohio: the corner of Grinn and Barrett.