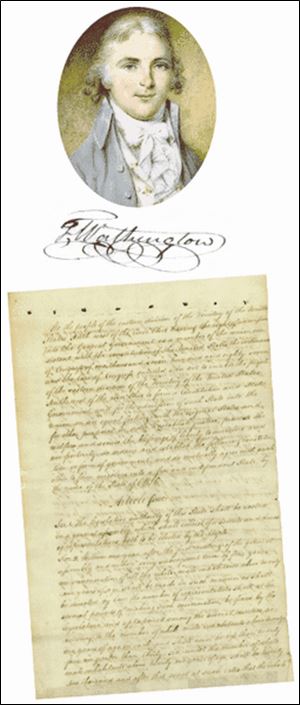

Ohio's constitution: Scribbled in haste in a Chillicothe pub

3/2/2003

Ohio's first constitution, as 19th-century storytellers tell it, was written in a hurry in a Chillicothe tavern by the infamous Michael Baldwin, who was probably holding a whiskey bottle in the hand that wasn't holding his pen.

"Poor, brilliant, boisterous, drunken, rollicking Mike" was a Yale-educated lawyer whose chief pastimes were drinking, gambling, brawling, and stiffing his creditors. He went on to become the first Speaker of Ohio's House of Representatives, where he presided with equal energy over all-night card games and the enactment of Ohio's first laws.

In November, 1802, Ohio needed a constitution as its ticket to becoming a state. The state-to-be was the most populated part of “the territory northwest of the river Ohio” — the Northwest Territory — the vast area of frontier and Indian country that England had given up at the end of the Revolutionary War. The individual states had in turn ceded to the federal government their claims to various parts of the territory.

The United States, having just fought a war to throw off colonial status, thus found itself in the embarrassing position of having colonies of its own. The Congress of the Confederation solved this problem through a series of acts, culminating in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, guaranteeing that territorial rule would be only temporary.

Under the ordinance, as each part of the territory reached a large enough population, its people could adopt a constitution and create a state, which could then enter the union “on an equal footing” with the original states. The people would be citizens of a sovereign state and not subjects. The ordinance's approach to territorial governance, revolutionary at the time, became the standard model for the nation's westward expansion over the next hundred years.

From the beginning, the people of the territory chafed under the autocratic “colonial” rule of the despised territorial governor, Arthur St. Clair. It was easy to despise St. Clair. Imagine Benjamin Franklin in all of his humor, learning, and humanity. Now imagine the exact opposite. That was Arthur St. Clair.

In April, 1802, representatives from the territory persuaded a willing Congress to call for a constitutional convention to establish the Northwest Territory's first state. For most people, it probably didn't matter what the convention came up with. All that mattered to them was that Ohio get a constitution and get it fast. While the circumstances called for speed, the delegates were conscious of their place in history. They went to work with a view not simply to establishing a government for the state, but to creating the very character of the state itself.

Mike Baldwin was one of the leading delegates to the convention when it met in November, 1802. We can be sure that the 19th-century stories exaggerated the extent of Baldwin's constitutional authorship, if only because we know that a lot of what went into the document was plagiarized intact from the constitution that Tennessee had adopted six years earlier. But his influence was still very evident in the convention's product.

For pursuit of the deadly sins was not Mike Baldwin's only passion. He also passionately distrusted, indeed despised, virtually all authority, and he was a passionate believer in essentially pure democracy. “The people are fully competent to govern themselves,” he said. “They are the best and only proper judges of their own interests and their own concerns. ... [I]n forming governments and constitutions, the people ought to part with as little power as possible.”

The constitution approved on Nov. 29, 1802, reflected that belief. In common with most American constitutions, the document had two primary parts: a set of detailed rules defining the structure and mechanics of the state government — the boring part — and a Bill of Rights. Today we tend to think of bills of rights as the primary bastions of individual liberty. Two-hundred years ago, there was a much sharper sense that liberties could be more broadly and effectively preserved by using the structural parts of the constitution to hobble the government's ability to act at all.

The delegates to the 1802 constitutional convention did just that. They hijacked Tennessee's Bill of Rights, with some editing, and then devoted most of their energy to creating a governmental structure in which officialdom would find it hard to function without strong popular support.

Governor had no power

On its surface, the constitution followed the classic structure established by the federal constitution, with executive, legislative, and judicial branches. But the executive — the governor — had about as much power then as the Queen of England has today: no veto, not much opportunity for patronage, and, unlike the Queen, the need to run for re-election every other year.

The judiciary didn't fare any better. There was a Supreme Court, but the justices were appointed by the General Assembly and the court's operations were under close legislative control. For the first 20 years, the justices spent most of their time riding circuit and rarely had an opportunity to sit as a single body.

When they did get together they seem to have spent a lot of their time swapping horror stories about godforsaken hamlets and miserably uncooperative horses, instead of actually deciding cases. During that time, the court's opinions weren't published, so that, all-in-all, there wasn't much opportunity for the court to do the kind of common-law lawmaking that might have been a source of independent legal and political power.

In fact, when the Supreme Court did show some independence, it was quickly reined in. In 1807, in the case of Rutherford vs. M'Faddon, the court took the startling step of holding a piece of legislation unconstitutional. The General Assembly responded by impeaching two of the justices.

The impeachment failed when its proponents fell a few votes short of the two-thirds needed to convict and remove the justices. The assembly then adopted the “sweeping resolutions,” declaring that the terms of all state officeholders, including judges, would come to an end in 1810. The vacancies were filled with more respectful — or at least compliant — jurists, people who took seriously the proposition that “the people” are “the best and only proper judges.”

Courts won the battle

In the long term, the courts won the battle, as courts usually do. The power of judicial review is today universally accepted, even if individual exercises of the power are regularly greeted with outrage and stinging criticism.

In fact, the decision in Rutherford, which has never been officially published and which would have been unfamiliar to 99 out of 100 lawyers five years ago, has lately enjoyed a renaissance. In 1999, it was cited as precedent by the Ohio Supreme Court for the very first time.

In the short term, the unsuccessful impeachment and the sweeping resolutions had their intended effect. Thirty years passed before the court started finding statutes unconstitutional again. And the delay wasn't due to a lack of opportunity; it was a question of self-preservation.

All of this might sound as though the 1802 constitution put the legislature in the driver's seat. But that wasn't the case. The General Assembly was certainly the center of whatever power the state's government had. But the constitution kept the legislators on a short leash too. Members of the House of Representatives had to run for re-election every year, and senators had to run every two years. If the assembly strayed from the popular will, the electorate always had an immediate opportunity to correct the problem.

The system, in short, was only one or two steps removed from running a state government by town meeting. Even in that heyday of Jeffersonian democracy, Ohio's constitution and the government it created stood out as radically populist — or nearly anarchist — institutions.

Second Constitutional Convention

During the 1830s and 1840s, however, the constitutional model of radically populist democracy grew increasingly uncomfortable. Certainly, having annual state-wide elections must have started to get a little old after a while, especially for people with real jobs and those with businesses to run.

The table on which the constitution was signed is in the Ross County Museum.

More to the point, the state had become a percolating part of the national market economy. There was still plenty of radical populism, with large pockets of intense hostility to banks and corporations and a thriving abolitionist movement. But the state also was increasingly influenced by people with a strong interest in political, social, and legal stability as the foundations of economic development. These were the kind of people who would have been very nervous around the likes of “boisterous, drunken, rollicking Mike” Baldwin.

It took a while to get there — mainly because the 1802 constitution was inordinately hard to amend — but in 1850 the interests of enough interest groups had sufficiently converged to permit the calling of Ohio's second constitutional convention.

The convention's product, Ohio's 1851 constitution, was not an entirely radical departure from the 1802 edition. The Bill of Rights survived pretty much intact, though with some editing, and it continues in force, with a number of additions, today. But the 1851 document did begin a movement away from the radically populist constitutional structure of 1802 and toward more conventional ways of conducting a government, with a stronger executive and a more independent judiciary.

Ohio moved even closer to the constitutional mainstream following constitutional conventions in 1874 and 1912. The 1874 convention proposed a whole new constitution, but the voters rejected it. In the following years, however, some of its fundamental features — such as finally giving the governor the power to veto legislation — were adopted one-by-one.

Amendments add initiative vote

The 1912 convention was more immediately successful. With the strong support and influence of the Progressive Movement, the constitution was amended to provide for, among other things, municipal home rule, workers compensation, and reform of the judicial system.

Harking back to the theme of popular democracy, the 1912 amendments also included the first provisions for initiative and referendum, giving the electorate a device for direct control over legislation. The amendments also required that the voters be asked every 20 years whether the state should hold a new constitutional convention. The question has been on the ballot four times starting in 1932. Each time the electorate has said no.

The biggest change from the original, 1802 constitution may well have been the fundamental shift in how the constitution limited the opportunities for legislative folly. The 1802 constitution gave virtually unlimited power to the General Assembly, but it made the individual legislators constantly return to the public for approval of their work.

The 1851 constitution doubled legislative terms and thereby reduced opportunities for the electorate to be heard. At the same time, however, the constitution included a series of prohibitions against specific kinds of legislative acts — such as lending the state's credit to private companies — that were supposed to be the product of interest-group politics.

The anti-authoritarian populism of 1802 had become the anti-special-interest populism of 1851 and beyond.

Echoes of the 1802 populism can still be heard in today's constitutional and public-law debates. The Supreme Court's mantra in public-records cases — “public records are the people's records” — could easily have come from the mouth of Michael Baldwin. As the Supreme Court's exercise of judicial review has become more aggressive over the past 25 years, the General Assembly's response has at times readily brought the Rutherford controversy to mind.

But now the assembly doesn't impeach the justices. Instead, as in the school-funding case, it shuffles some papers and ignores them. This is probably an improvement. Michael Baldwin — who once went after Governor St. Clair with a knife — might well have preferred to just take the offending parties outside for a good whuppin'.

Charles Hallinan is a professor of law at the University of Dayton school of law, where he has taught for 20 years. He formerly practiced law in Toledo at the former law firm of Lehman, Kaplan, Lenavitt, and Richardson. He is a 1977 graduate of the University of Toledo college of law.