The new frontier: A magnet to settlers

3/2/2003

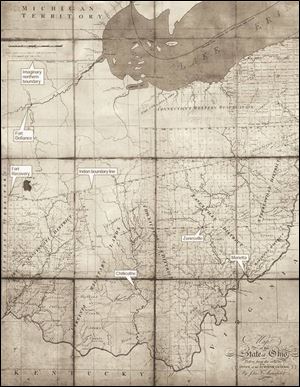

In 1806, three years after Ohio became a state, John F. Mansfield of the Office of the Surveyor General drew this map. It shows about half of the state plotted into square townships. The Virginia Military Lands in southern Ohio, the western portion of the Connecticut Western Reservation, and all of the northwestern part of the state still under Indian control had yet to be divided into townships. Counties had been formed throughout the state, except in the Indian lands, where Fort Recovery and Fort Defiance are the only organized settlements. The Maumee River and Maumee Bay were labeled the Miami River and Miami Bay, their original names.

CHILLICOTHE, Ohio — Two hundred years ago, settlers arrived by horseback, traveling miles through pristine woods to witness the birth of Ohio at its first capital.

The new state was an unending wilderness, with towering trees and large tracts of swamps.

“Huge wild grapevines festooned the ancient hardwoods,” Emily Foster wrote in The Ohio Frontier. “Bears, elk, and wolves roamed the forests... Buffalo browsed on the prairie and along the rivers. To settlers from New England, even the milder climate of Ohio was a siren's call.''

Most of the northern half of the state was still labeled Indian Territory on maps from the period. Ohio was America's new frontier, with land aplenty that could be cleared and settled.

There were Indians to deal with and battles yet to be fought to gain control of the rest of the state.

Settlers in Marietta at the time described Ohio as a “mixed mass of people, scattered over an immense wilderness, with scarcely a connecting principle. ''

In the late 1700s, Ohio was a prize and its story is how white settlers who traveled west worked hard and fast to change the land, Ms. Foster wrote.

“Only by understanding what Ohio was like two hundred and more years ago is it possible to grasp how much it has been changed by successive waves of immigrants, starting with the first European settlers,” Ms. Foster wrote in the 1996 book she edited.

If there was a “connecting principle” among the settlers, it was what could be accomplished with the plow, the saw, and the ax.

Yesterday, thousands gathered at the state's first capital again to kick off the celebration of its bicentennial, with the Ohio General Assembly holding a session where the first state legislature met 200 years ago.

“The creation of Ohio was one of the great acts of the American Enlightenment,” wrote Andrew R.L. Cayton, a history professor at Miami University, in Ohio, The History of a People, a book published last year.

“Its founders did not consider the state distinctive or romanticize its landscapes and its peoples. Such things did not matter to them because they were not trying to create something unique. Rather, they were making a political community designed to exemplify a larger experiment in universal brotherhood. ''

Before the Revolutionary War, the land that became Ohio was a “shadowy image in the minds of eastern colonials,” wrote George Knepper, a history professor at the University of Akron.

“Only a few traders willing to risk their lives for profits knew its forest trails and the Indians who traveled them. But soon after the war ended, Americans surged westward in irresistible numbers. Ohio was located directly in the mainstream of this migration, and as America grew, so did Ohio,” Dr. Knepper wrote in Ohio and its People.

In 1806, three years after Ohio became a state, John F. Mansfield of the Office of the Surveyor General drew this map. It shows about half of the state plotted into square townships. The Virginia Military Lands in southern Ohio, the western portion of the Connecticut Western Reservation, and all of the northwestern part of the state still under Indian control had yet to be divided into townships. Counties had been formed throughout the state, except in the Indian lands, where Fort Recovery and Fort Defiance are the only organized settlements. The Maumee River and Maumee Bay were labeled the Miami River and Miami Bay, their original names.

The issue facing the new nation was how to organize, govern, and develop the western lands that Great Britain ceded to the United States in the 1783 Treaty of Paris.

On July 13, 1787, the Congress of the Confederation approved the Northwest Ordinance,creating the Northwest Territory — a vast expanse of land stretching from Pennsylvania to the east, the Mississippi River to the west, the Ohio River to the south, and Canada to the north.

The Northwest Ordinance established a territorial system of government, with a powerful governor and provisions enabling creation of a legislature when the number of white adult men reached 5,000 and application for statehood when the population hit 60,000.

“By enacting the Northwest Ordinance, Congress finally had a method that would make expansion into the territory orderly and measurable,” wrote Tanya West Dean and W. David Speas in Along the Ohio Trail.

Four of the original colonies claimed parts of the Northwest, with New York, Virginia, and Massachusetts surrendering their land to Congress. Connecticut also gave up its land claims, but Congress set aside land for the colony in what became northern Ohio. The area was called the Western Reserve or the Connecticut Western Reservation.

With the exception of the Fire Lands — set aside for Connecticut citizens whose homes were burned by the British and the Tories during the American Revolution — Connecticut sold the land to speculators in 1795. The Fire Lands are in Erie, Huron, and parts of Ottawa and Ashland counties.

“The story of early Ohio was the story of the dispossession of the Indians,'' wrote Ms. Foster in The Ohio Frontier.

White settlers viewed the people who already lived in the Old Northwest as an obstacle to the push west.

Jonathan Alder, who was kidnapped as a child by Indians and grew up with them, described how white settlers retaliated when Indians hijacked settlers' barges and attacked isolated colonists.

“Driven from place to place, our favorite hunting grounds taken from us, our crops destroyed, towns burned, and our women and children sent off in the midst of winter, perhaps to starve, while the warriors stood between them and their enemies,'' Mr. Adler wrote.

After several tribal leaders gave up two-thirds of Ohio in the 1795 Treaty of Greenville, white settlers moved beyond the Ohio River settlements, up the Miami and Scioto rivers to claim land, build homes, and set up farms.

“They cut, cleared, milled, and mined, slaughtering predators and prey as fast as they could, occupying the land for white civilization,” Ms. Foster wrote.

In 1796, Congress approved speculator Ebenezer Zane's plan to carve a wagon road from Wheeling to Fort Washington at the Ohio River. In 1790, 3,000 white settlers lived in the territory that later became Ohio. By 1800, the population had increased to 45,365 white people.

On April 30, 1802, President Thomas Jefferson signed into law the "Enabling Act” that set the boundaries of what would become Ohio and gave its people the power to draft a constitution.

At the time, Columbus was “practically an unbroken forest, marked here and there with puny settlements.” The closest grist mill and post office were 45 miles away in Chillicothe.

And that's where the 35-member Constitutional Convention met on Nov. 1, 1802, to draft a constitution. The document, which took only 29 days to complete, set Ohio's first election for January, 1803. It gave the right to vote to white men over 21 who paid taxes and had lived in the state for at least one year.

The Ohio Constitution didn't allow slavery in Ohio.

“Many of these settlers came to Ohio after having freed their slaves,” wrote historian Robert E. Chaddock in Ohio Before 1850. “Others had no slaves and because they could not compete with the economic system that fostered slavery left the South seeking better opportunity.”

In Democracy in America Alexis de Tocqueville compared Kentucky, where slavery made labor “degrading,'' with Ohio, where people could “profit by industry and do so without shame.''

Although the state constitution didn't allow slavery in Ohio, a proposal to give blacks the right to vote was rejected when Edward Tiffin broke a 17-17 tie. Born in England, Mr. Tiffin moved from Virginia to Ohio. A physician and Methodist lay preacher, he became the state's first governor in 1803.

At Ohio's centennial celebration, B.W. Arnett, a black clergyman and former state legislator, said: “In 1802, my race was denied the oath in courts; we were denied the right to carry a gun; we were denied the jury box; we were denied the cartridge box; and we were denied everything in those two boxes.''

Women also could not vote, serve in the militia, hold office, or take part in any jury deliberations, said Dr. Cayton, the Miami University history professor.

Thomas Worthington — who had played a key role in preventing Arthur St. Clair, governor of the Northwest Territory, from making it difficult for Ohio to become a state — met with President Jefferson on Dec. 22, 1802, and also submitted the new constitution to Congress.

President Jefferson signed a bill into law on Feb. 19, 1803, extending the federal laws of the United States to “the State of Ohio.” The first Ohio General Assembly, made up of 30 representatives and 15 senators, met for the first time on March 1, 1803, in Chillicothe. Mr. Tiffin was sworn in as the first governor.

A year later, the Ohio legislature approved an act to forbid “black and mulatto persons” from living in the state without a legal certificate of their freedom, Dr. Cayton said.

In 1803, Ohio became the “first state of the Old Northwest.”

What was the United States of America like in its early days?

From Monticello to the White House, President Jefferson had to cross eight rivers, five without bridges or ferries. Noah Webster was working on three dictionaries — for schools, business offices, and an unabridged version. The most advanced houses — three stories and made out of wood — could be found in Salem, Mass.

The holdings of American families were valued at $1.8 million — about $2,000 for each family of five whites.

“... the difference between the poorest and richest free men was much smaller than at any time since,” wrote Marshall Smelser in The Democratic Republic: 1801-1815.

“Europeans were baffled, really. Americans hustled for money, not to hoard it, but to spend it liberally and to speculate audaciously. This was not the European pattern of greed. Travelers re-embarked for Europe, shaking their heads at the puzzle of an energetic people as interested in spending and risking as in getting,” wrote Dr. Smelser, a University of Notre Dame history professor.

From 1800 to 1810, America's population increased from about 5.3 million to 7.25 million.

Only one of every 25 people lived in a city and in 1800, the largest was Philadelphia, with about 69,000 residents.

“Most towns had organized volunteer fire departments,” Dr. Smelser wrote. “And most of them smelled terrible, especially during hot dry spells, when garbage and excrement accumulated in the rat-infested, pig-ridden streets.''

But outside the few towns, settlers inhaled the “organic yeasty smells of farmyards and barns, the sweet fragrance of new-cut timothy and clover, the damp, fresh smells of forests, wood smoke, the weak perfume of fresh flowers,” he wrote.

“The range of tastes was narrow: salty or smoked meats, rare natural sweets, bitter coffee and tea, and the emphatic warmth of strong drink or the sour foaming of small beer,” Dr. Smelser wrote. “Rural sounds were few: animal cries, ax blows, birdcalls, children's voices, and always the wind in the trees, sometimes provoked to gales and blizzards.''

In 1800, America had about 200 newspapers.

“After the Bible and the sermons, they probably had more influence on the American mind than all of the novels, plays, and essays put together,” wrote Dr. Smelser. “The newspaper was almost the only literature the American yeoman had time for. ''

Politics led to the state capital of Ohio moving from Chillicothe in 1810 to Zanesville, back to Chillicothe in 1812, and finally to Columbus in 1816.

But for settlers, the most pressing issues beyond their own safety were transportation and access to markets.

When Ohio became a state in 1803, the legislature required that 3 percent of the money from selling public land would be spent to lay out roads. Improvements to Zane's Trace led to formation of towns including Zanesville, Lancaster, Somerset, and St. Clairsville.

Merchants traded goods for agricultural commodities, which they sold locally or shipped for sale to Cincinnati, Louisville, St. Louis, and New Orleans.

Two hundred years ago, the average lifespan for Ohio men was 34 and 36 for Ohio women, wrote R. Douglas Hurt, a professor who specializes in agricultural history at Iowa State University.

Even after the Indians were gone, settlers complained of the “sheer loneliness of the forest, where the trees cast a permanent shadow and one might not see another white face for months on end,” wrote Ms. Foster, in the book she edited, Ohio Frontier.

Settlers sometimes waited one month for mail and socializing for most was tied to hard work.

“All participants came from far and near to raise the log cabin of a settler amid the forests,” historian Robert E. Chaddock wrote in 1908. “After the work of the day the young people spent the night in merriment and dancing, while the older folk told stories and chatted beside the blazing fire.''

In the summer of 1804, Joseph Gibbons considered moving from Chester County, Pennsylvania, to land near Steubenville, Ohio.

“The cost of living was low, and the price of land was going up. Indians were no longer a serious threat. ... When Gibbons first saw the Ohio River, which was the ‘handsomest' he had ever seen, he could not help but contemplate ‘the future grandeur of this western world — when this Stream should be covered with vessels spreading their canvass to the wind, to convey the produce of this fertile country to New Orleans and across the Atlantic Ocean,” wrote Dr. Cayton.

Mr. Gibbons returned to Pennsylvania and sold his land there. He, his wife, and three children moved to Ohio.

“Breaking with centuries of European tradition, the founders of Ohio, like the founders of the United States, created no standing armies, no established churches, no entrenched aristocracy to ensure stability,” wrote Dr. Cayton. “Rather, they imagined that the thousands of ordinary white men who were populating the state would create their own institutions and rely on each other for support and protection.”