Isle Royale offers rugged nature lab

7/14/2003

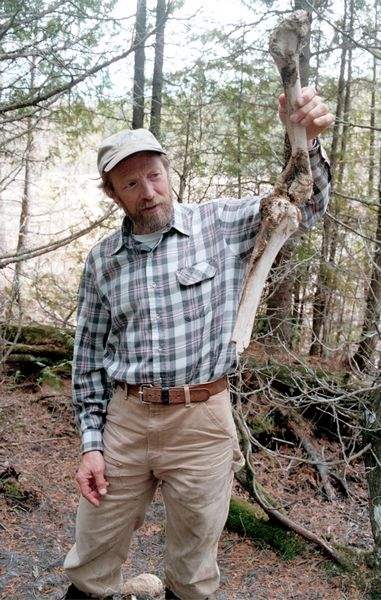

Rolf Peterson, an expert researcher of wolves, holds a bone from a moose that wolves recently killed.

henry

Rolf Peterson, an expert researcher of wolves, holds a bone from a moose that wolves recently killed.

ISLE ROYALE, Mich. - Stare down a moose in the secluded woods of Maine or Ontario and you'll feel an adrenaline rush.

Do it on Michigan's Isle Royale and the sensation could be even more intense because you won't have a vehicle around to take cover. Vehicles are not allowed on the island.

You won't be carrying a gun, either, at least not if you're abiding by National Park Service regulations. So you'll be face-to-face with a wild animal that weighs in excess of 1,000 pounds and has no fear of humans. All the moose fear are the fangs of Isle Royale's most elusive resident: wolves.

Tucked way up in western Lake Superior, Isle Royale is about as far away from Toledo as residents can travel into Michigan in distance and culture. A 44-mile stretch of forested rock, it has one of the world's largest concentrations of wolves and moose.

It is an archipelago of 400 tiny islands that has become much more than a back-to-nature experience for the granola-munching crowd. It gives some a euphoric feeling as they hike the island's 165 miles of foot trails, lugging backpacks through rocky terrain and bogs until they unwind around a campfire at night and listen to the distant call of a loon.

But in a broad sense, Isle Royale - a national park since 1931 - has become one of the world's best metaphors for how nature can never be wholly separated from man's influence.

Scientists have come to view it as a unique outdoor laboratory for studying two things in particular: the predator-prey relationship of wolves and moose, plus the nowhere-to-hide impact of toxic airborne pollutants, especially mercury from coal-fired power plants.

So much mercury has settled on Isle Royale's lakes and streams that people are still advised to limit their consumption of the island's fish, years after power plants and factories in the region installed equipment to control air pollution.

University of Minnesota researcher Deb Swackhamer considers that a sad indictment of society, given there is no industry or automobiles for miles. Isle Royale is so isolated that the quickest boat ride - from Grand Portage, Minn. - takes three hours.

“It has been infected and insulted by pollutants for decades, she said.

The island's biggest body of water, Siskiwit Lake, is “a microcosm out in the middle of nowhere” of the kind of damage that airborne pollution can cause to unspoiled ecosystems, she said.

Even industrial chemicals banned in the 1970s, such as cancer-causing PCBs, remain a nagging problem because they volatize into the air as water warms up. They are found at higher concentrations in Siskiwit Lake than in Lake Superior, no doubt because the volume of the former is only a fraction of the latter, Ms. Swackhamer said.

Although fish are less polluted than 30 years ago, they face an emerging threat from a harmful class of chemicals known as PBDEs - one of the hotter research topics among scientists. Commonly used for years in furniture padding as a flame retardant, PBDEs have become airborne and doubled in concentration every five years throughout North America, she said.

A fish-cleaning house is owned by the Sivertson family, the last ones to own a commercial fishing license in the area.

“The biggest threat to Isle Royale without a doubt is mercury,” Ms. Swackhamer said. “PBDEs are a big item because we just don't know much about them yet.”

Residents of the Great Lakes region often can feel disconnected from nature, seemingly unaware of the rugged quest for survival that still goes on in this part of the world between various species, such as the wolves and moose of Isle Royale.

Isle Royale is America's least-visited national park with about 19,500 visitors - roughly the same that Yellowstone National Park gets in a summer day.

Although wolves and moose have thrived, both have faced struggles against Superior's bitterly cold winters and disease. The moose population hit 2,400 animals in the early 1990s, only to crash twice in the last decade. Its current population of 900 still maintains the island's stature as one of world's densest populations for moose. Isle Royale's wolf population hit a high of 50 in 1980. Though it is now down to 19 animals, it remains one of the world's densest wolf populations.

“I am told that every Norwegian child learns the story of Isle Royale's wolves and moose in elementary school,” the island's premier wolf researcher, Rolf Peterson, wrote in his book, The Wolves of Isle Royale.

Moose are believed to have swum over from the Canadian mainland in the early 1900s. With no predators around, their population skyrocketed until a 1936 fire burned a quarter of the island's browse. Then, during an exceptionally cold winter of 1948-49, an ice bridge formed over Lake Superior - a lake so vast and deep it rarely, if ever, freezes over. The ice bridge allowed a small pack of wolves to cross Lake Superior. Since then, the wolves have become an important check-and-balance for the island's moose population, according to the park service.

Despite their elusiveness, wolves have not been immune from man's influence, either. As Mr. Peterson's book pointed out, wolf teeth have evidence of the radioactive fallout of thermonuclear weapons and the Earth's accelerating rise in carbon dioxide emissions from power plants, factories, and automobiles. “For any thinking human, this should underscore the scale of modern human enterprise, and should hint at the magnitude of the challenge of maintaining natural processes in our national parks,” he wrote.

As plentiful as the moose has been for the wolves, a kill is not as automatic as one might think. Wolves are successful in killing moose in only about 5 percent of their tries. The rest of the time, wolves feed on smaller animals, such as beaver, Mr. Peterson said.

Isle Royale was not always as wild as it is now, another sign of its resilience. Settlers mined it for copper in three rushes during the 1800s. Throughout much of that century and into the early 1900s, it was a popular site for commercial fishing.

Airborne pollution probably would have crippled the commercial fishing industry there by the mid-1970s, if economics had not phased it down on its own, Ms. Swackhamer said. Commercial fishing was impacted largely by competition from recreational boaters and the destruction of lake trout by the invasion of non-native sea lamprey. Lamprey entered the Great Lakes in the early 1900s when the Welland Canal was built to help ships get past Niagara Falls.

“Lake trout aren't for food any longer. They're just fun for the sportfisherman,” according to Howard “Buddy” Sivertson, a member of the last family which still owns a commercial fishing license there.